A story of a child who fought the Nazis his own way

For Yiddish educators, creating child heroes was an emotionally safe way to relate Holocaust history to their students

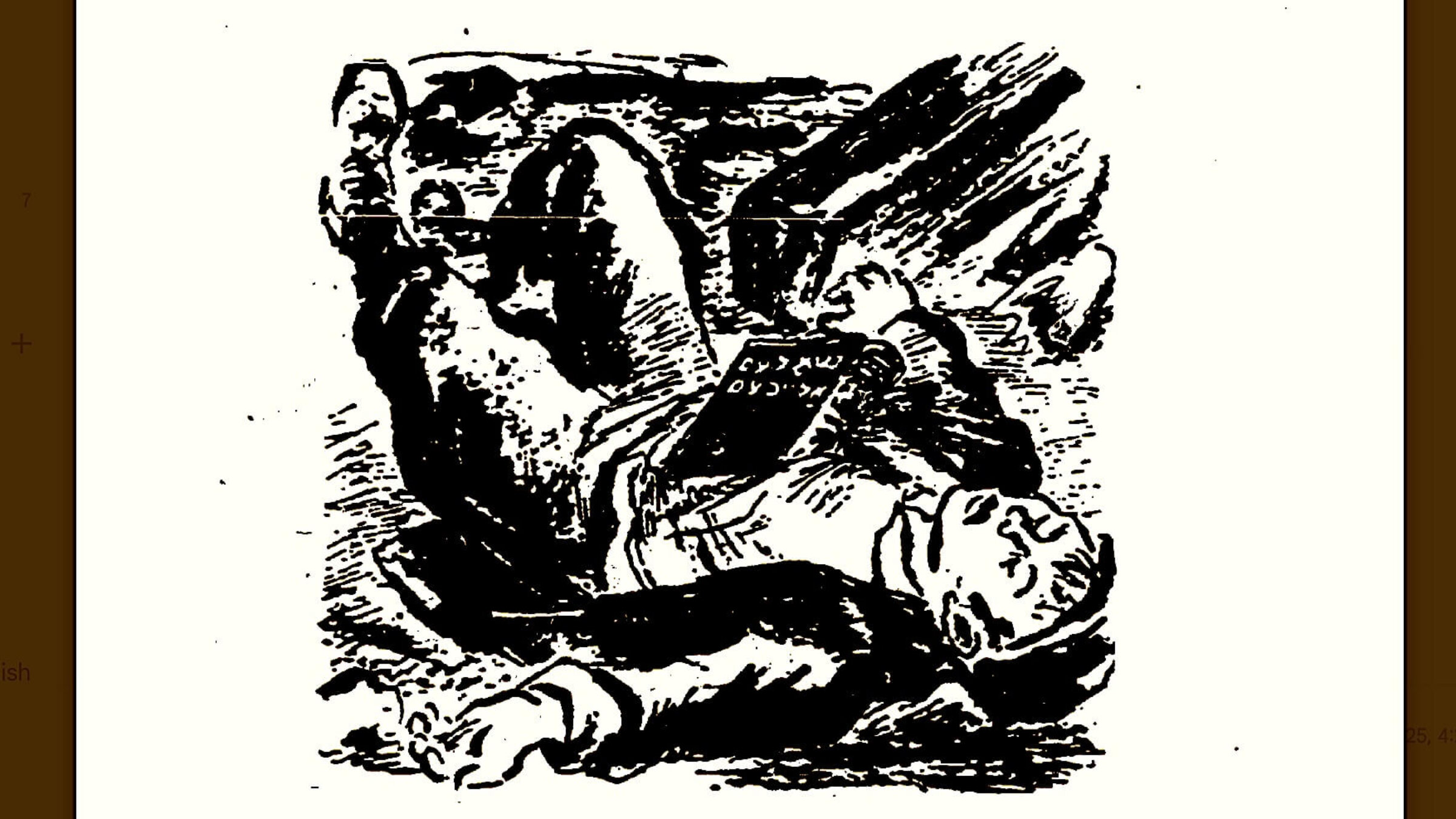

Image by IKUF

In Yiddish, the Holocaust is known as der driter khurbn, the Third Destruction. That designation is a clear sign that for Ashkenazi Jews, the decimation of European Jewry was spiritually and historically identical to the destruction of the two ancient Temples in Jerusalem: first, by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, and then by the Romans in 70 CE.

The story which I’ve translated below closes out the Forverts project of the year 5785 — our year-long exploration of the Jewish holiday cycle through Yiddish children’s literature.

Because the fast day of Tisha B’Av (The Ninth of Av) — the somber holiday commemorating the Temples’ destruction — falls during the summer, it gets short shrift in Yiddish school anthologies and other collections of holiday tales. Secular Yiddish summer camps took the day as an opportunity to connect the deep and recent past, commemorating the tragedy in Europe.

Just as the ancient catastrophes yielded a liturgy of lamentation, the events of the Holocaust gave rise to poetry, testimony, fiction and drama. Survivors and more distant witnesses put pen to paper and paint to canvas, seeking to document the horror and make meaning of it.

But educators in the Yiddish school networks of North and South America faced a special set of challenges: how could they inform their pupils about the fate of Europe’s Jewish children without overwhelming them with the sense of hopelessness and helplessness? The solution: They focused on imagining the small gestures of resistance, instances of extraordinary and everyday heroism, that could be undertaken even by elementary school-aged children.

Yuri Suhl (identified in Yiddish as M.A. Suhl) and his colleagues in the leftist organization YKUF pulled together Holocaust children’s literature that had appeared immediately after the war in Yiddish youth periodicals, publishing an anthology in Buenos Aires in 1953 under the title Kinder heldn (Child Heroes). These fictional stories and poems depict children who support the fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Some of them even join the partisans fighting in the forests. These young heroes often care for children even younger and more vulnerable than them, like one story in which two best friends smuggle infant twins out through Warsaw’s sewers to the relative safety of a forest encampment.

This story, “The Little Sholem Aleichem,” describes a boy who engages in a profound act of spiritual resistance during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: preserving and circulating the last remaining volume of the Collected Works of Sholem Aleichem among the “schools” that were improvised even in wartime ghettos. In this way, he “saves” the classic Yiddish humorist, and by extension, his cultural heritage.

Children can indeed be heroes. And stories of their heroism can — and should — be read by adults too. May these depictions of young people’s grace and grit in the worst of circumstances motivate us to agitate for a world in which all children enjoy safety, dignity and peace.

“The Little Sholem Aleichem” by M.A. (Yuri) Suhl

It was the month of April. There was a springtime chill in the air, but in the Warsaw Ghetto, it was hot as high summer because of the fierce battle raging there. Houses burned, guns fired, bombs exploded, Jews ran this way and that, young and old, rich and poor, strong and weak: whoever was still standing lent a hand to the battle the Nazis.

But one boy — his name was Shloymele — lay in a pit and stuck his head out from time to time to see how the fighting was going. He was no coward, Shloymele. He wasn’t hiding out of fear. He too was fighting — in his own way.

Whenever the battle drew close, he would jump up and dash on his thin, nimble legs to another hole, or behind a wall, or behind a pile of bricks, or onto some rooftop. That’s how he fought the Nazis: darting and hiding.

You see, Shloymele carried a thick Yiddish book tied with string around his thin, scrawny frame. And over the book, he wore his old, torn, black kaftan, long outgrown and shrunk so small it came down only to his knees. Lying in his hiding hole, whether behind a pile of bricks or up on a rooftop, he clutched the book to his body with both hands.

He guarded that book like the apple of his eye, having made up his mind that under no circumstances would the book fall into the Nazis’ hand, unless they first took his — Shloymele’s — life. For as long as he lived, he wouldn’t let the book out of his hands. That was his contribution to the fight against the Nazis.

In the great tumult of battle, nobody even noticed him. No one paid attention as he ran from one hiding place to another. Even his friends, the boys his own age, and his teacher were too busy with the battle to think about him now. Only he, Shloymele, kept his large eyes alert to all that was happening around him.

He was hungry, thirsty, tired, drowsy, and terribly weakened, and his eyes were heavy with exhaustion and wanted to close — but Shloymele pushed through and forced himself to stay awake, for fear that he might fall asleep and allow the Nazis to snatch away his book.

In the streets lay many dead bodies, piles of bricks, and shards of glass. The air carried a great many screams and cries, shouts and sobs. More than once, he felt like screaming or crying out in terror. But he held it in because he was afraid that if he screamed or cried, he would give up his hiding place, and the Nazis would grab the book.

Many of the stories printed in that book, he knew almost by heart. And often, lying in a hole at night, he felt an urge to untie the string and take the book out from under his kaftan and read over the stories once again by the flickering firelight of the burning walls. He even considered memorizing all the stories so that if he lost the book, he could still go from class to class and retell the stories to the children word for word.

But he was afraid that if he untied the book, he might not have time to retie it around himself.

From time to time, when he got really thirsty and when the fighting let up a little, he crawled cautiously out of his hole and crept furtively on his belly to a house to search among its empty rooms for some water or a bit of bread. Occasionally, he would find a little musty water or a crust of dry bread. That’s how he kept up his strength.

But on the final day of the fighting, on a May dawn, when everything was burning all around and the Nazis had captured the entire Ghetto, Shloyme had scrambled out from his hole with his last strength to look for a new hiding place.

As soon as he left, bullets from Nazi guns began to whistle overhead. Terribly weakened and disconcerted by fear, he broke into a run, not knowing where to. Suddenly he felt a sharp blow to his chest and fell — unconscious.

By this time,almost all the Jews in the Ghetto had been killed and the few who remained alive had escaped to the Partisans, the freedom fighters, in the forests. Among the survivors was a brave, bold boy called Velvl.

A tall, strong Jew, one of the partisans, ordered Velvl to run through all the streets to see who was still alive and to let him know, so that the wounded could be taken into the forest and saved.

Scampering over the piles of bricks and rocks, Velvl noticed his school mate Shloymele.

“Shloymele!” he cried out, bending over him; Shloymele didn’t respond. His eyes were shut, and from his nostrils came shallow breathing. But Velvl didn’t notice his breathing. Right there on the spot, he decided to take Shloymele with him into the forest, even if he was no longer alive. He went to summon the Jewish partisan, telling him breathlessly:

“Come quick, quick!” he said, pulling the man by the hand.

“You found someone?” the man asked.

“Yes,” said Velvl, “It’s Sholem Aleichem.”

“Whaddaya mean, Sholem Aleichem?” the partisan rested his eyes on the boy. ‘You mean the writer?” “Yes,” said Velvl, “the writer.”

“Are you out of your mind?” the man asked, visibly annoyed. “You’ve picked some time to joke around. Sholem Aleichem the writer has been dead for years. He died in America.”

“Yeah, yeah, I know that, but this is the Little Sholem Aleichem.”

“Well congratulations!” the man shouted at Velvl. “The little Sholem Aleichem? Maybe next you’ll discover the medium-sized Sholem Aleichem!”

“I swear on my life I’m not joking,” Velvl said. “I recognize him. This is the Little Sholem Aleichem. And if you won’t help me, I’ll drag him all by myself,” Velvl said, into tears.

“That’s your fever talking, my child,” said the man more softly. “Come show me where he is, your Sholem Aleichem, because every moment is precious.”

Velvl led the Jewish partisan over to Shloymele, who lay motionless next to a pile of bricks. He bent over the boy, placing a fingertip to his nostrils and laying one ear to his heart.

“Strange,” said the man, “he’s breathing, but his heart isn’t beating.” He quickly unbuttoned the boy’s kaftan and spotted the thick volume from Sholem Aleichem’s Collected Works tied around Shloyme’s heart. The book’s cover was embossed in gold with a portrait of Sholem Aleichem. One of the author’s eyes had been pierced by a bullet. The partisan untied the string, picked up the book and rifled through its pages. The bullet had lodged midway through the volume, in the middle of a story called “Baranovitsh Station.”

Velvl laid his ear to Shloyme’s chest. “It’s beating, it’s beating!” Velvl exclaimed happily.

“Yes,” nodded the Jewish partisan. “Sholem Aleichem saved his life.”

He handed Velvl the book and lifted Shloyme from the ground. “Come!” he said, “Let’s get going before it’s too late.”

…

Later that evening, by a small fire in the woods, Velvl explained to the rest of the partisans and evacuees just who Shloyme was. He told them about how, in the Jewish schools of the ghetto, only a single volume of Sholem Aleichem’s Collected Works had remained. And since Shloymele was a nimble, agile kid who’d slipped through the Nazis’ fingers more than once, he was tasked with taking the book from one school to another. It was his duty to guard it, and he’d always carried out this obligation. Over time, he came to be known among the children and teachers as the Little Sholem Aleichem.

Here in the forest, Shloymele once again hid the book on his person at all times. And occasionally, the Jewish partisans would borrow it from him and hold a reading of Sholem Aleichem’s tales. But here in the forest he was no longer called “The Little Sholem Aleichem”; here he was called “Panie (Mister) Sholem Aleichem.”