How this Jewish day school teaches students about the Holocaust

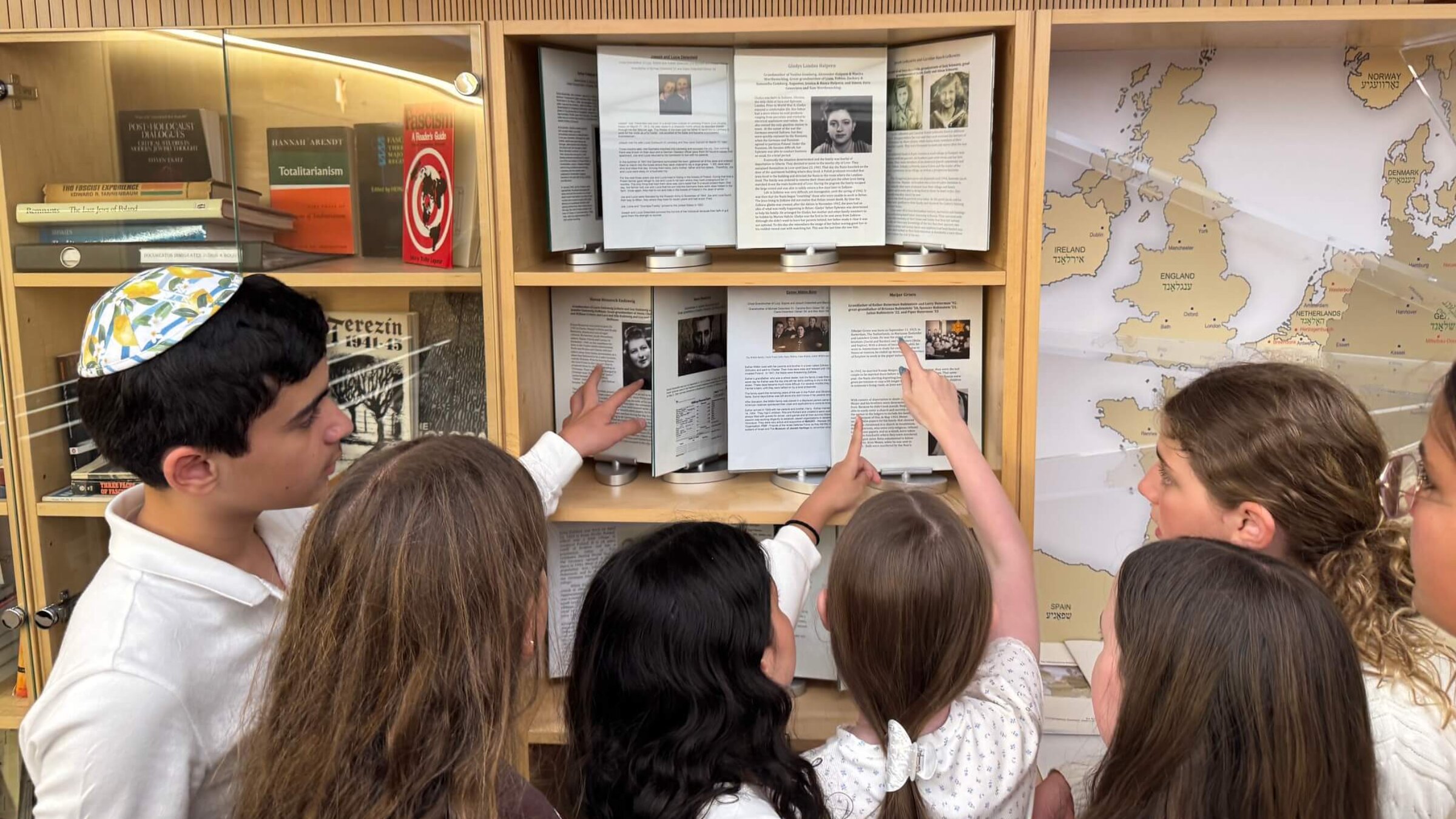

Students at the Ramaz Middle School view a map in English and Yiddish, as well as artifacts contributed by community members

Students at the Ramaz Middle School visit the Holocaust library on Yom Hashoah, April 23, 2025 Photo by Camryn Bolkin

Tucked away among the sacred texts and Torah scrolls at my synagogue is something unusual: a Holocaust library.

That synagogue is Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun (KJ), a large Modern Orthodox shul on Manhattan’s East Side.

My mother, architect Yaira Singer, designed and installed the library in 2017 for the 1,200 families who belong to the synagogue. She said she was inspired by the Holocaust Museum and Study Center at the Bronx High School of Science.

The centerpiece of the space is a bilingual map of Europe, in Yiddish and English. Lucite panels, resembling shattered glass, intersect the map and converge on the six major Nazi death camps in Poland, representing the convergence of Jews from all over Europe in the Final Solution.

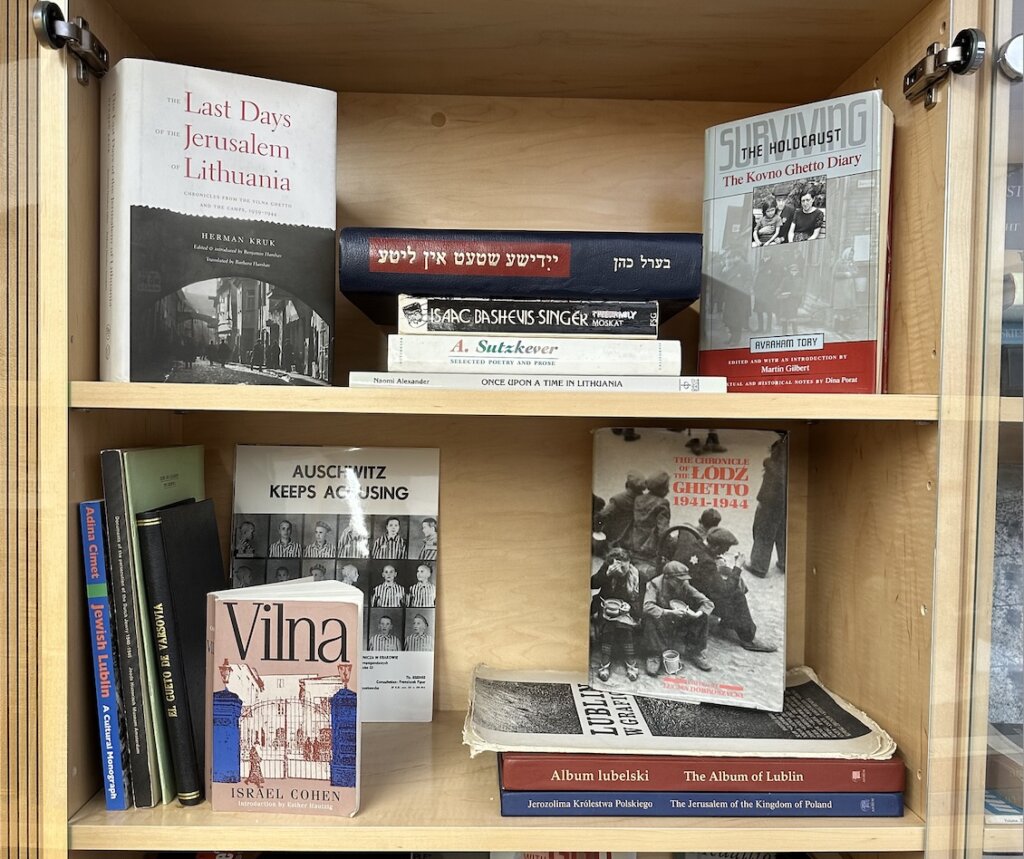

Flanking the map on both sides are Holocaust-related artifacts contributed by members of the community. They include books, photographs and written testimonies, collectively paying tribute and preserving the memory of both victims and survivors.

The library was developed collaboratively by a committee of KJ synagogue members and parents from the Ramaz School. Although the two institutions operate independently, they share some physical spaces, resources and rabbinic leaders.

“We created the library as a physical and symbolic anchor for Holocaust education in our community,” said library committee member Julie Kopel.

As a result, each year on Yom HaShoah, students from Ramaz Middle School visit the library as an introduction to the school’s social studies unit on the Holocaust. When I visited with my class as a fifth grader in 2019, my classmates and I crowded around the map. We avoided the jagged lucite panels, which some immediately connected to Kristallnakht, the Night of Broken Glass. We searched for familiar names and pointed when we found our ancestors’ hometowns.

Library committee member Yonina Gomberg said that the exhibit could hit close to home for many of the students. “Hopefully, it will inspire them to learn the stories and bear witness as well,” she said.

In addition to the personal connection, Holocaust education at Ramaz is framed around the idea of highlighting the cultural richness and scholarly traditions that existed prior to the destruction of European Jewry. Eighth-grade history teacher Tzipporah Ross begins her curriculum with a study of Jewish cultural and religious life in pre-war Eastern Europe. Influenced by the approach of her own professor when she was a student at Columbia University, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Ms. Ross focuses on historical Jewish figures, such as the Lithuanian Talmudist known as the Vilna Gaon; the Chafetz Chaim — a revered rabbi who was known for his teachings against evil speech; the Polish Hasidic rabbi Rabbi Meir Shapiro, and Sarah Schenirer, a Polish-Jewish seamstress who pioneered the first religious Jewish day schools for girls.

“It’s only after getting a sense of the robust, thriving communities that were there before the Holocaust, that students can begin to appreciate the magnitude of what was destroyed,” Ms. Ross said.

Students also complete a research project on a pre-war Jewish community, using digital tools like WeVideo, photographs from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), and historical reference texts such as the Encyclopedia Judaica. Some students choose towns connected to their family histories, while others are assigned locations.

The hope is that through this project, students will come to understand that many aspects of Jewish life in Europe — family structure, religious observance and communal celebrations — were similar to their own. To further this message of connection, images of Jewish life before the war, like children riding bicycles and families celebrating milestones, are juxtaposed with similar scenes from contemporary Jewish life. These parallels emphasize the cultural continuity across generations and encourage students to see Holocaust history as intimately related to their own identities.

One challenge in connecting contemporary students to this past is the language barrier. Yiddish was the primary spoken and written language of many Holocaust victims, yet Ramaz doesn’t offer formal Yiddish instruction, and the synagogue’s Yiddish club, called “Yiddish Schmoozers,” no longer meets.

Despite that, the Holocaust library gave Yiddish a home at Ramaz and KJ by including a curated collection of Yiddish poetry by Abraham Sutzkever, songs by Mordechai Gebirtig, and anthologies such as the yizkor book (memorial book), Jewish Cities and Towns in Lithuania, by Berl Cohen. Yizkor books are volumes of remembrance compiled by survivors of a city or town that document Jewish life there before it was decimated at the hands of the Nazis.

Including Yiddish literature in the library serves two key purposes. First, it highlights the literary and cultural heritage that was destroyed. The loss of Yiddish literature during the Holocaust through censorship, the burning of books and the deaths of its writers is an often-forgotten cultural tragedy. By collecting and showcasing these texts, the library helps honor this aspect of Jewish culture. Second, it preserves and makes accessible primary texts, serving as an open invitation to connect to our cultural memory. The mere act of offering access and visibility gives Yiddish a presence in the community.

While few people in the community speak Yiddish, Dr. Daniel Kokin, in his second year as the Ramaz Upper School librarian, spent some time at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, before he began working at the library. “It was a pleasant surprise to discover some Yiddish volumes amid the Ramaz Holocaust education library at KJ,” Dr. Kokin said. “I borrowed one of them and have been reading it at home.”

Entitled “Vilna, mein Vilna” the book is by Abraham Karpinowitz, a Yiddish writer whose stories depict everyday life, including those of Jewish criminals, in pre-war Vilna. “May the Yiddish works in this library inspire Ramaz students and parents to cultivate an interest in mameloshn,” Kokin said.

Hopefully, having a school librarian who understands the library’s value for young students, could inspire them to learn more about the language.