Yiddish life in prewar Eastern Europe comes alive on this website

Through photos, maps and many short essays, its pages are not static memorials, but invitations to explore

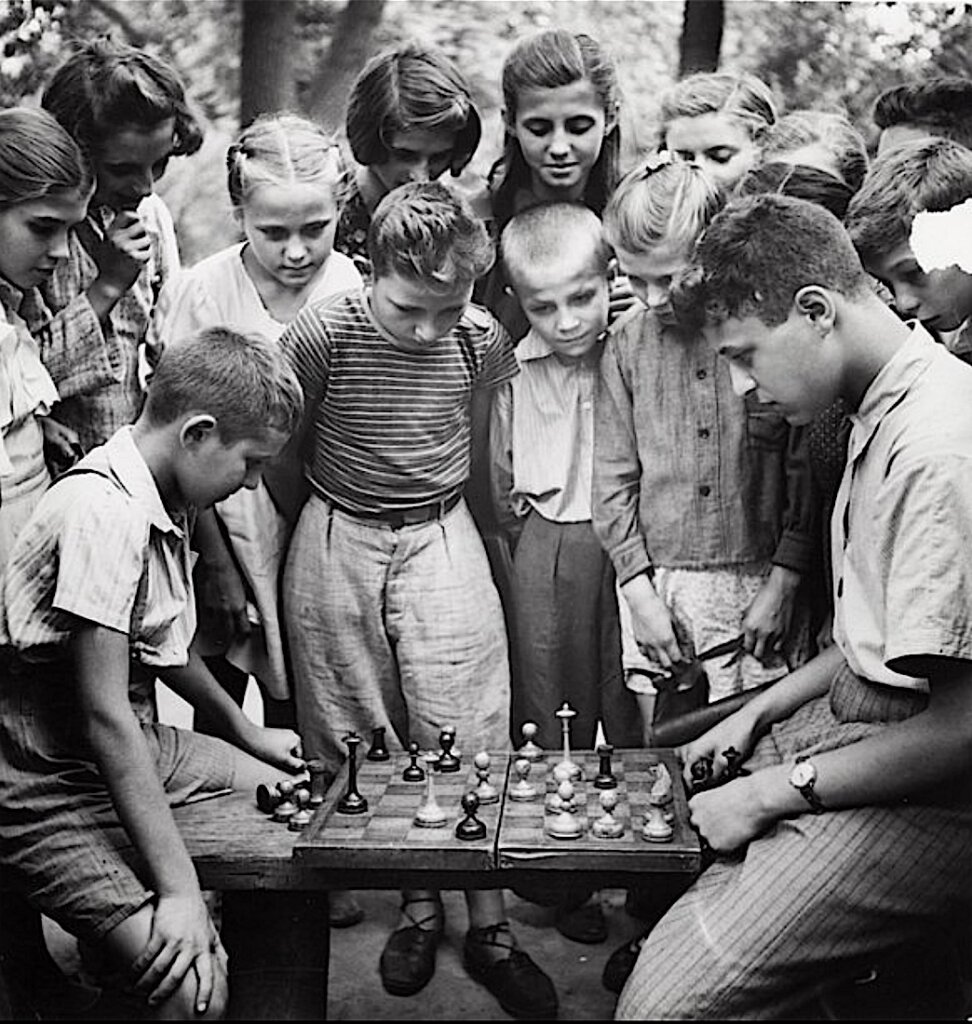

AI-enhanced image of children in the Jewish neighborhood of Warsaw, Poland before the Holocaust. Photo by Yad Vashem — Holtzberg Warsaw Pictures

On a quiet corner of the internet, a new website asks us to listen.

That site — “https://www.yiddishculture.co/” — is more than a digital exhibit; it’s an act of cultural restitution. Each page restores the sound, movement and texture of Jewish life that once animated the streets of Poland and Lithuania, before silence fell.

Yiddishculture.co. is the latest project by sociologist and educator Adina Cimet, founder of the Educational Program on Yiddish Culture (EPYC). The site intends to use an evocative idea: that language is not only speech but atmosphere.

Her goal, it seems, is to make the world in which Yiddish lived visible again — its culture, values, humor, its music, its human geography. Through layered maps, archival photographs and many short essays, EPYC transforms the abstraction of Eastern European Jewry into a living landscape of shtet, shtetlekh un derfer — cities, towns and villages of a world that was teeming with ideas and dreams.

A map of memory

At first glance, the site’s interface feels deceptively simple: a rotating globe dotted with the names Vilna, Lublin, Lodz, Kuzmir and Czernica. Click on any of them, and the screen opens on an illustrated panorama — markets alive with movement, children’s schools, synagogue facades and Yiddish signs standing quietly amid the rhythm of Jewish life. The pages are not static memorials, but invitations to explore.

For Cimet, who has worked teaching Yiddish language and culture in YIVO, this project arose out of a rejection with the “flattening” of Jewish Eastern Europe. “Shtetl should not evoke one homogeneous place,” she said. “There were many shtetlekh, each with its own accent, customs and political life. This project aims to restore that diversity.”

The culture of a people, not a relic

The site’s Culture section expands that vision. In elegant bilingual typography — Yiddish and English (though parts can be translated into other languages) — the reader encounters the interwoven strands of Jewish civilization: Language, Religion, Political Life, Food, Music, Shoah and more.

Each topic reveals vivid artifacts and explanatory essays. A poster from the Yiddish theater in Warsaw connects performance to questions of class and aspiration. In that world, the stage mirrored real life — where upward mobility, identity and humor were performed as much as lived. A 1930s cookbook reveals how “the Jewish kitchen was a bridge between faith and economy.” Political cartoons appear beside essays that trace the tensions between Bundist, Zionist and religious ideologies.

“The famous linguist Max Weinreich called Yiddish a ‘fusion language,’” one caption notes. “But fusion is not confusion — it’s creativity.” The site seems to take that statement as a guiding principle: Yiddish as an adaptive art of survival, where humor and holiness share the same breath.

The vast material on the site is accompanied by essays written by the most distinguished academics in the field, among them Samuel Kassow, Rakhmiel Peltz, Chava Turniansky, Mordkhe Yushkovitz and others.

Teaching the future to hear the past

The project doesn’t try to resurrect the past but rather provide the knowledge to help students inhabit that worldview — to see what those people saw and to reconnect with their challenges and goals.” The project is structured for educators who can build units around geography, literature or history. But it’s also a standalone tool for anyone interested in delving into the history and culture.

What makes When These Streets Heard Yiddish so moving is that it resists both sentimentality and detachment. It speaks to the generation that may have grown up hearing their grandparents’ Yiddish mixed with English or Hebrew, only half-understanding its cadences. Here, those cadences are given back — paired with images, texts and sounds that reanimate them. The result is part museum, part curriculum, part memorial and wholly alive.

Memory as education

EPYC’s design quietly models an educational philosophy that feels deeply Jewish: learning as remembrance, remembrance as responsibility. The Shoah section concludes with a simple line: “The Jews of Poland were not strangers to the winds of war” and a photo of deported children walking away from the camera. Yet even here, the tone is not only tragic. It gives special voice to what youth had to face and do then. The placement within the broader framework of language, food, song and sustained visions reminds the reader that destruction came after centuries of creativity.

Cimet understands that digital space is now where memory must live. “But the most important challenge that the project aims for is to offer tools to invigorate the past in order to speak to the issues of the present,” she said. “Facing the problems of the day in diaspora communities and in Israel, to be offered a way to find the root of the ideas and values that propelled Jews to where we are today, is the best way to reassess what values and goals we have, which we lost and need to reshape as Jewry everywhere struggles to survive.”

“If we can’t walk these streets anymore,” she said, “we can at least hear them. And by hearing, begin to imagine again.”