Magnificent new Judaica gallery at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts

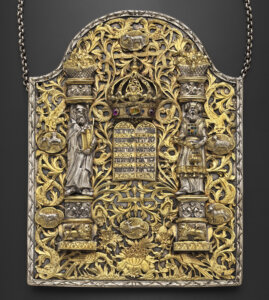

Among the objects: a Torah shield created in 1781-82, with images of intertwined plants and animals — some real, some fantastical.

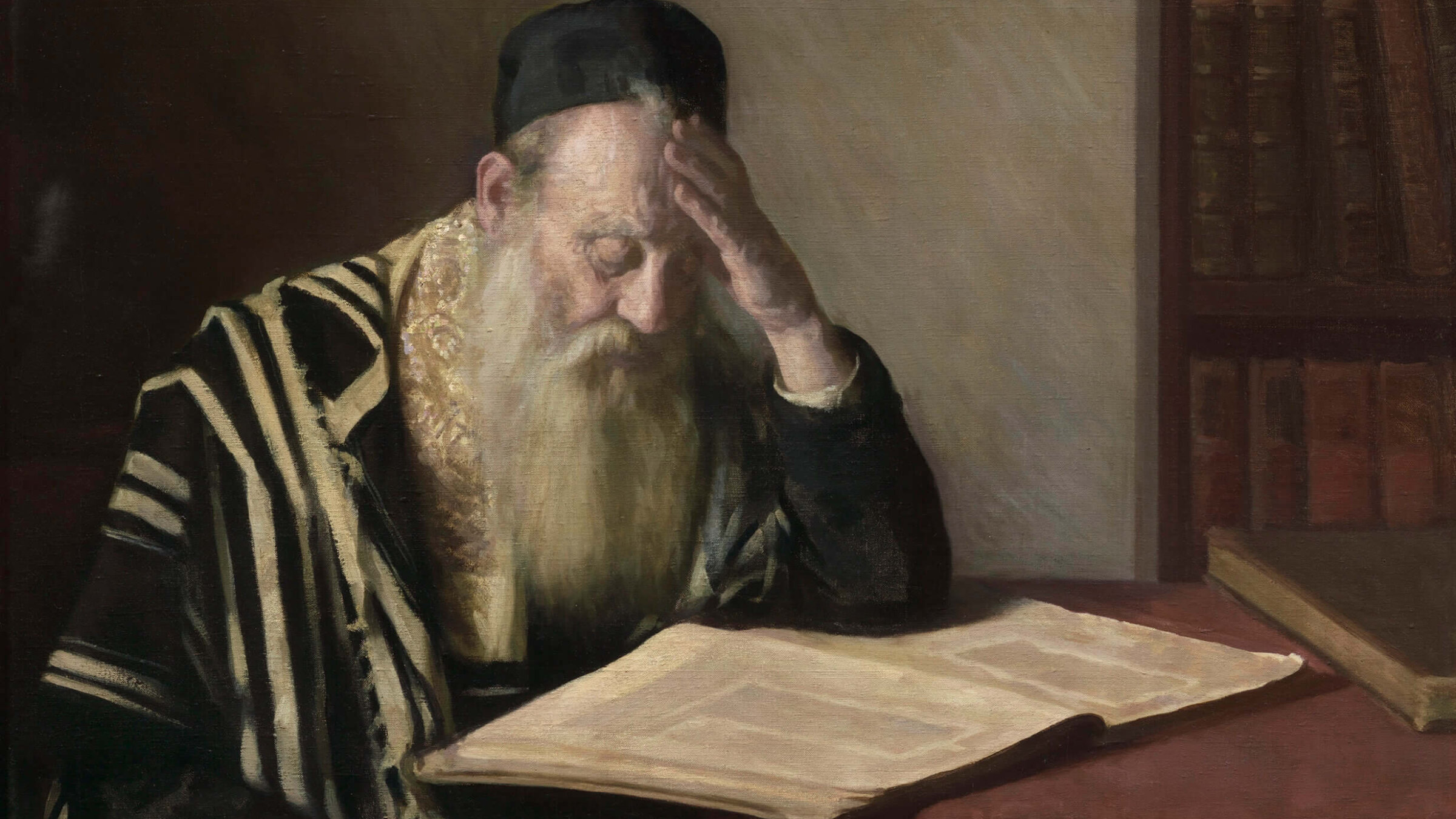

The Talmudist Jacob Binder, 1919. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

To stand in the new gallery of Judaica in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) is to experience the power of objects to tell stories.

Together, the elegant objects and paintings that make up Intentional Beauty, Jewish Ritual Art from the Collection reflect Jewish resilience and dedication to beauty found through Jewish practice, despite centuries of dispersion, exile and persecution, across the continents.

No matter which country Jews have found themselves in — Iran, Morocco, Yemen, India, Italy or the United States — the craftsmanship of these magnificent objects testifies to their makers’ dedication to Jewish life and practice.

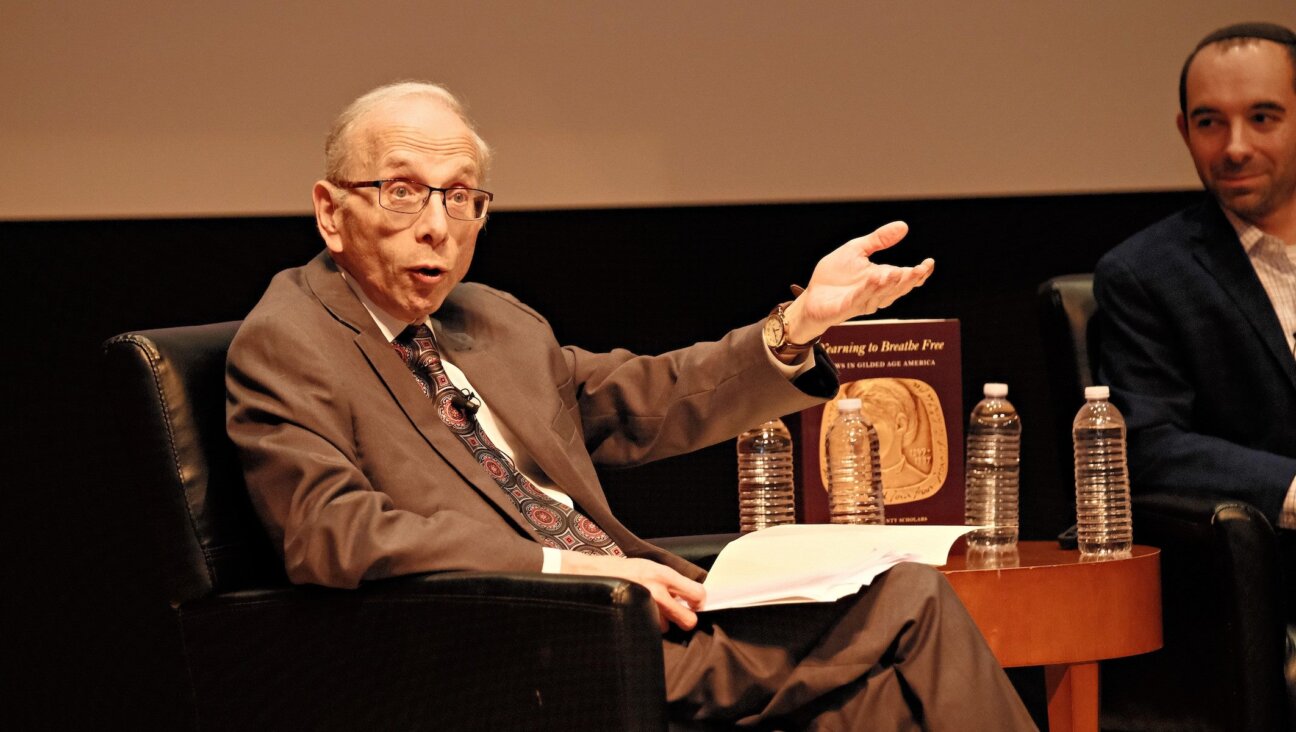

The MFA is one of only four U.S. art museums (as opposed to Jewish museums) that include Judaica galleries. The others are in North Carolina, Minnesota and Houston. In December 2017 the Italian-born Simona Di Nepi was hired as the first dedicated curator of Judaica at the MFA, and at the time, the first full-time Judaica curator at a global museum in the world.

One of her goals, De Nepi said, was “to put Jewish culture and Jewish art on the physical and figurative map.” While there are Judaica objects scattered throughout the museum it’s incredibly powerful to now have Jewish objects in a dedicated space. Di Nepi has acquired 45 objects since she was hired.

The majority of the objects in the new gallery are now on display for the first time. The masterpiece in the center of the room is a silver Torah shield from Galicia, probably from Lvov, (now Lviv) in Ukraine, created in 1781-82. “This is a treasure not just of the gallery, of the Judaica collection, but of the European silver collection,” Di Nepi said.

As is the case with many of the objects in the gallery, you need to look closely to appreciate its mastery. A Torah shield is usually designed to be seen only from the front, but this one is intricately carved on both sides. On the front you can see a layer of gilded silver, with sinuous, swirling intertwined plants and animals, some real, some fantastical.

There are also three-dimensional figures of Moses and Aaron on it, flanking a jeweled crown (representing the Torah), and a replica of the Ten Commandments over a shield of silver. That same imagery of thick, intertwined plants and animals was once a popular decoration on the monumental pre-war synagogues in Galicia (now Eastern Poland and Western Ukraine) that were later destroyed by the Nazis.

The back of the shield is minutely engraved with the story of the binding of Isaac, with details impossible to see with the naked eye, a level of detail only usually seen in book engravings. Luckily, an interactive display screen actually allows you to magnify the image to catch the details, including the proud inscription on the back, in Hebrew: “This is the work of my hands, Elimelekh Tozoref of Stanislav, in the year 5542.”

Elevated on a platform, as if on a bimah, is another new acquisition — a Torah ark gifted to the MFA by Rabbi David Whiman. This is the central section of an original ark originally created by master woodcarver Sam Katz to contain the Torahs at Shaare Zion synagogue in Chelsea, near Boston. Katz was born in 1884 in Veshnevets, modern Ukraine, and emigrated to the US in 1910. After living in upstate New York, where he carved two Torah arks, Katz settled in Chelsea, where he opened a wood-making store and made two dozen arks in the 1920s and 1930s, all inspired by synagogues of Eastern Europe that were later destroyed by the Nazis.

When Shaare Zion closed, Rabbi Whiman saved the ark, and as he traveled from one post to the next, the ark traveled with him. The MFA’s Conservation department returned the ark to its fine, elegant form, with its gilded lions, Magen Davids, an eagle and flowers on the top, and in the middle — two gilded hands of Kohanim (Jews of the priestly class) giving a blessing, thumbs touching, all gleaming against the dark wood.

Looking to track down former congregants of Shaare Zion, Di Nepi posted about it on Facebook and many responded. They were “very excited and emotional,” said Di Nepi. “This is the chance to tell the story of Jewish Chelsea, where at one point roughly half the population was Jewish, with 15 to 20 synagogues in two square miles.”

Adjacent to the ark is a gilded lion, one of 5,000 works of folk art originally donated to the MFA in 1960 by a Russian American Jewish opera singer and collector, Maxim Karolik. This lion was once part of a pair that held the Ten Commandments over the ark in the Anshai Poland synagogue in Boston. When the synagogue was demolished in 1957, the ark was dismantled. Karolik bought the lion from an antique store in Boston’s south end, unaware of its Jewish story. Now one can see how the carpenter, Katz, carved the wood so it seems supple; the lion, seen mid-roar, is strong, vigorous and proud, its mane rippling.

Showing the diversity of Jewish experience in the diaspora, on display is a tik, a Torah case made in Iraq, where it was the custom to have a hard embossed silver Torah case, a standing container, rather than a mantle. “What is wonderful about this work besides the level of detail and craftsmanship of an art that was passed down from Jew to Jew in Baghdad is the story that it tells,” said Di Nepi. In researching the provenance, Di Nepi discovered that this Torah case, while made in Iraq, came from India. In essence, said Di Nepi, “We have Iraq and India in a single object.”

Also testifying to Jewish roots in India is a recently acquired Haggadah, published in India in 1874, opened to a page showing women in saris baking matzah, written in Hebrew and translated into Marathi. This book belonged to the Bene Israel (Children of Israel), who moved to Mumbai in the 19th century. Since light causes the pages to deteriorate after six months, these pages are only displayed for a short time.

There are no objects here from the Holocaust except for a print of a black and white photo taken by photojournalist Henryk Ross, of a man rescuing the Torah from the rubble of the Lodz Ghetto in 1940, cradling it in his arms as if it were human. “I felt like it says everything we need to say,” said Di Nepi, “about the value and importance of the Torah and of the textiles that cover it in Judaism.”

That reverence for the Torah — the ark, the tik, the pair of gorgeous finials made in 1729 by the earliest known Jewish silversmith in England — imbues this space.

There is a danger, of course, once one puts objects from the past behind glass, of this becoming a gallery of relics of a dead civilization. That’s why there’s an entire wall of contemporary Judaica here, as well as an example of Tamar Paley’s feminist reinterpretation of ritual objects, such as tefillin as jewelry for women.

There’s an old Jewish concept known as hiddur mitzvah, which means putting extra time or resources into a mitzvah so that it’s performed as beautifully as possible. In this single gallery, you sense the devotion to hiddur mitzvah of the past several centuries, which can give visitors hope for the future of Jewish life and ritual and — something much needed now — something to celebrate.