Atop the Ivory Towers

A few weeks ago I went out to dinner with Bob and Anita Summers, two distinguished economists who long taught at the University of Pennsylvania. Afterward they invited me back to their lovely home in the hills of Truro, one of the most beautiful towns on Cape Cod. In the course of the evening, as we looked out across the dunes and the bay toward Provincetown, they noted how amazing it would be to their immigrant parents, who struggled in the mean streets of Chicago and New York City, to see where they were these days.

As I sat there, I was taken by the fact that not once in the course of our conversation did the Summerses mention that their son Larry had done all right in America, too. The former secretary of the treasury of the United States was now the president of Harvard.

“Imagine,” I can hear my own parents say, “Harvard has a Jewish president!” They would be equally amazed to know that this is also true of Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, Williams and Trinity College. Princeton has had a Jewish president. Dartmouth has had two. Each of these is an institution founded by members of one or another Protestant denomination, and all, for many, many years, were correctly seen as bastions of white-shoe WASPdom. Such schools, in the days of widespread and quite open antisemitism, were places that guarded their gates with euphemistically labeled “geographic quotas” that severely restricted the enrollments of those of a certain ethnic and religious “persuasion” (read: Jews) from cities such as New York. These realities remained in effect well into the 1950s.

Truth to tell, there has been more of an evolution than a sea-change in opportunities for Jews in academia, first in the professoriate, then in the administration of many of our most prestigious colleges and universities. The first break seemed to come around the time I was entering the profession, in the mid-1950s. For example, my field, sociology, long dominated in this country by Protestant ministers and reform-minded Christians, was already being inundated by outsiders, some of them refugees from Europe, others the sons and daughters (mostly sons) of those who belonged to the Workmen’s Circle and more radical organizations. Our mentors seemed ready to accept us because, after all, we were studying “social problems” and “social issues,” and many a field site was an immigrant enclave or black ghetto. Those in other fields, some in the social sciences like economics and political science, and many in the humanities, engineering and the biological sciences were far less welcoming. (“What,” a famous Harvard English Department story goes, “can they tell us about our language?”) But that was to change, too.

By the 1960s, Jews were found in almost all departments and steadily, as they rose through the ranks, they moved into leadership positions as department chairs and, sometimes, as deans. Still, the idea of a Jewish college president in any place but Yeshiva University or Brandeis was almost about as unthinkable as having a Jew in the White House. But it happened. Today there are many Jewish college presidents. Or, perhaps, it is more accurate to say that there are many college presidents who happen to be Jewish. They are not there because they are Jews but because they were considered the best candidates for the highly coveted positions.

Not all are eager to carry the Torah, figuratively or literally (as Lawrence Summers has done at Hillel services). Indeed, many are much closer, at least in outward appearances and operating style to the sort of individuals I once described as “JASPs,”or Jewish Anglo-Saxon Protestants. This does not mean that they deny their background or their ascribed identity. They don’t. (Well, most don’t.) But they prefer to see themselves and be seen in a different way. They do not feel it is important to wear a label on their sleeves, and sometimes feel very uncomfortable when probed about how they “as Jews” see, say, American Middle-East policy or affirmative action.

The fact is that, as more Jews moved into presidential suites in Princeton’s venerable old Nassau Hall and similar places all around the mid-Atlantic and New England, faculty members, students and the public learned something that Jews, especially those who kvell so much about “our Jewish presidents,” have sometimes forgotten. There are not two Jews who are the same. Not in the shtetl, not in the suburbs and not in Princeton, or Williamstown or Cambridge.

In the old days, before Justices Goldberg, Fortas, Ginsburg and Breyer joined the Supreme Court, many Jewish Americans were proud to speak of “the Jewish justices” — Cardozo, Brandeis and Frankfurter — as if they were identical triplets. Anyone who looked into it, or read their opinions, would have quickly learned that they were very different in background, temperament and judicial philosophy. So it is with today’s “Jewish” justices — and college presidents.

Still, there is nothing that says the children and grandchildren of those who came to America in search of a dream can’t be as proud of the fact that those with whom we are, willy-nilly, identified have made the grade. I know I am. I’m sure Bob and Anita Summers are, too.

Peter Rose, senior fellow of the Kahn Liberal Arts Institute and Sophia Smith professor emeritus of sociology at Smith College, is the author of “Guest Appearances and Other Travels in Time and Space” (Swallow Press, 2003).

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

- 2

Opinion Trump’s Israel tariffs are a BDS dream come true — can Netanyahu make him rethink them?

- 3

Fast Forward Cory Booker’s rabbi has notes on Booker’s 25-hour speech

- 4

News Rabbis revolt over LGBTQ+ club, exposing fight over queer acceptance at Yeshiva University

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Is this extremist Zionist group trying to protect Israel — or just punish left-wing Jews?

-

Fast Forward Conservative movement softens support for two-state solution

-

Theater William Finn, Tony-winning writer of queer, Jewish musicals dies at 73

-

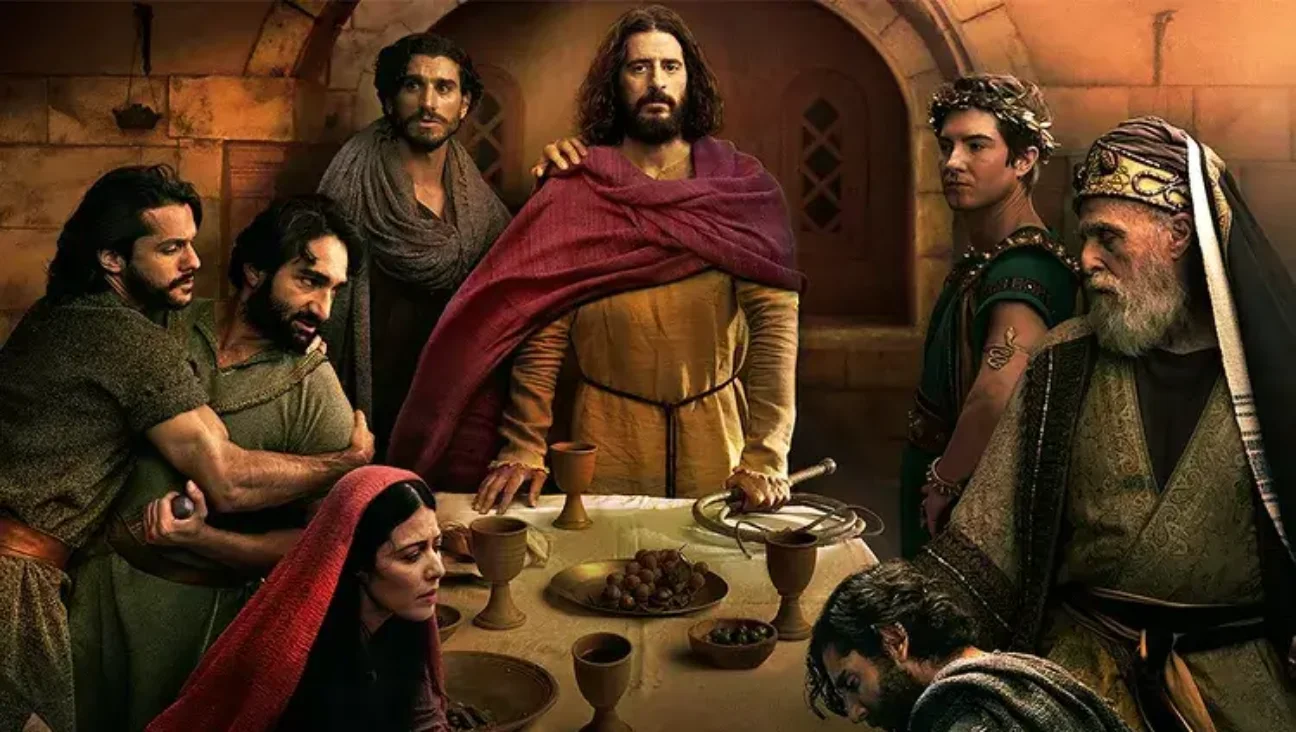

Culture The only good Jews in this hit Christian TV show are the ones who follow Jesus

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.