Music That Saves?

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

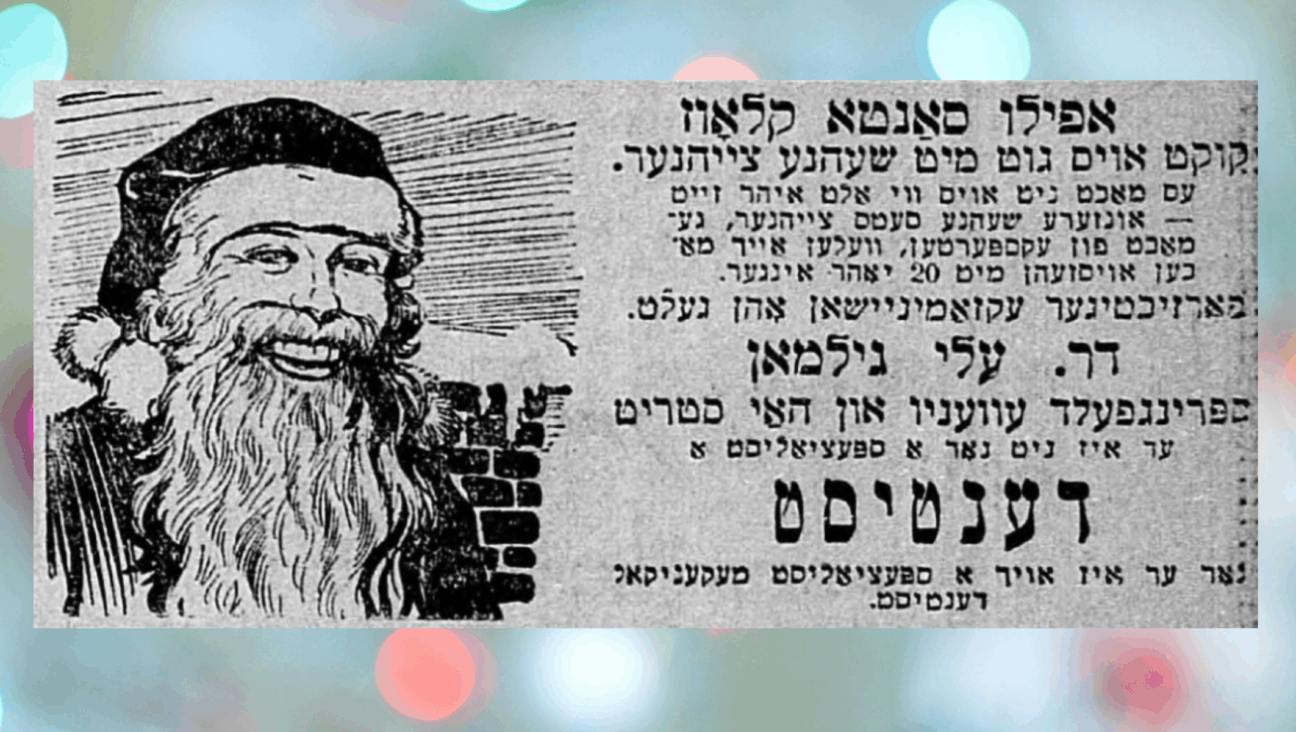

Isn?t It Divine? : The high altar of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, flanked by two menorahs ? a gift from Adolph Ochs, the Jewish founder of The New York Times. Image by lora lavon dole

Birkenau, known as the death camp of Auschwitz, was one of the few camps where music accompanied mass murder. For 54 women who knew how to play instruments, music was a life saver.

The Women’s Orchestra of Birkenau was the only such orchestra commissioned by the SS during World War II. The women played for the crowds newly transported to Birkenau, for the bleary-eyed and emaciated inmates forced to work each day and for the pleasure of their captors. In exchange, they were granted life. Given slightly better treatment than other inmates of Birkenau, they paid for it with their hard practice and with the emotional stress of playing while other prisoners were sent to their graves. Using only the instruments on hand, they played Chopin and Beethoven with mandolins, recorders and flutes. With the exception of their conductor, Alma Rose, all 53 women survived. Three are still alive today.

Now, the sounds of the orchestra can be heard once again, in performances commemorating the women who played for a year and a half at Birkenau. It’s their story of hardship and humanity that compelled contemporary conductor Barbara Pickhardt to create “Music in Desperate Times: Remembering the Women’s Orchestra of Birkenau,” which weaves orchestral music taken from the repertoire of the ensemble with spoken words from the memoirs of orchestra members and with songs of hope and resistance sung by an accompanying chorus.

The concert will be performed March 28 by Ars Choralis, a not-for-profit chorus from upstate New York, at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine in New York City. The group later this year will perform in a church in Berlin and at the liberation ceremony at Ravensbruck, an all-female concentration camp.

The Cathedral Church is a venue that many say suits the program perfectly. “The Cathedral of St. John the Divine has got an amazing history of social justice, a commitment that goes beyond any particular religious belief,” program director Alice Radosh said. “It is also one of the most, maybe the most, beautiful venues in New York City.”

St. John the Divine sees itself as a cathedral not just for Episcopalians, but also for the world. “The house of prayer for all people as it extends to other faith communities was envisioned in the beginning, but more as a civil gathering place for major civic events and for civic worship,” said Wayne Kempton, archivist for the Episcopal Diocese of New York.

It’s that openness and the group’s relationship with Thomas Miller, the Reverend Canon for Liturgy and the Arts, that brought “Music in Desperate Times” to New York City.

But above its mission to be a house of prayer for all people, beyond its bronze doors decorated with scenes from the Old Testament and past the images of Moses in its stained-glass windows, the cathedral has been an outspoken supporter of the Jewish community during hard times.

Even before the orchestra was assembled in April 1943, the cathedral, under the direction of Bishop William Thomas Manning, spoke out forcefully against the Nazis’ treatment of the Jews. “None of us, whether we are Jews or Christians, none of us who call ourselves Americans have the right to be indifferent to such acts,” Manning said on March 27, 1933, at a protest meeting against the persecution of Jews.

Manning also spoke out in favor of the United States going to war in Europe, much to the chagrin of some members of his diocese. And in the years after the war, the cathedral held symposiums on the Holocaust and concerts for Holocaust Remembrance Day. Elie Wiesel lectured at a 1974 Holocaust symposium at the cathedral and was named one of its official colleagues. When the Anglican Communion came out with a statement in 2005 calling to divest from Israel, Bishop Mark Sisk of the Episcopal Diocese of New York was in strong opposition, citing the powerful ties and deep friendship between the Episcopal Church and the Jewish community.

“The cathedral is an absolutely natural venue… for a special half-celebratory, half-commemorative event honoring this group because of the interdenominational, cross-cultural arts ministry and the cathedral’s consistent empathetic support of those who have suffered,” said Jeannie Terepka, the archivist at nearby St. Michael’s Episcopal Church.

And it’s a relationship rooted in history. The first chapel to be completed in 1911 was the Chapel of St. Saviour, funded by August Belmont, who was born August Schonberg to a Prussian-Jewish family. Two imposing menorahs of gold-covered bronze sit on the high altar — a gift from the late Adolph Ochs, the Jewish founder and publisher of The New York Times. In addition to the menorahs, he contributed $10,000 to the building fund.

The world’s largest gothic cathedral, St. John’s seats the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. Priding itself on reaching out to all people, it runs various social service programs for the community. Given the demographics of the city, and the cathedral’s location on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the Jewish population is hard to ignore. Terepka says that the “connection is borne out in the iconography, both traditional and innovative, of the cathedral itself.”

Inside the cathedral, a statue of Albert Einstein is included in a historic parapet dedicated to outstanding characters in each of the first 20 centuries. Representing the 20th century alongside Einstein are Susan B. Anthony, Mahatma Ghandi and Martin Luther King Jr. Ties with the Jewish community are strong on broader issues — like the support for Israel and the eradication of human suffering — but not in the cathedral’s daily operations. Programming with nearby synagogues is sparse.

But that seems insignificant when, consistent with its mission, the cathedral salutes the survivors by hosting Pickhardt and 63 musicians in performance of such pieces as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto and Puccini’s “Un Bel di Vedremo,” all performed 66 years earlier by the brave women of the Birkenau orchestra.

Lana Gersten is a frequent contributor to the Forward.