Appreciating Elon, The Writer Who ‘Put a Name on a Moment in History’

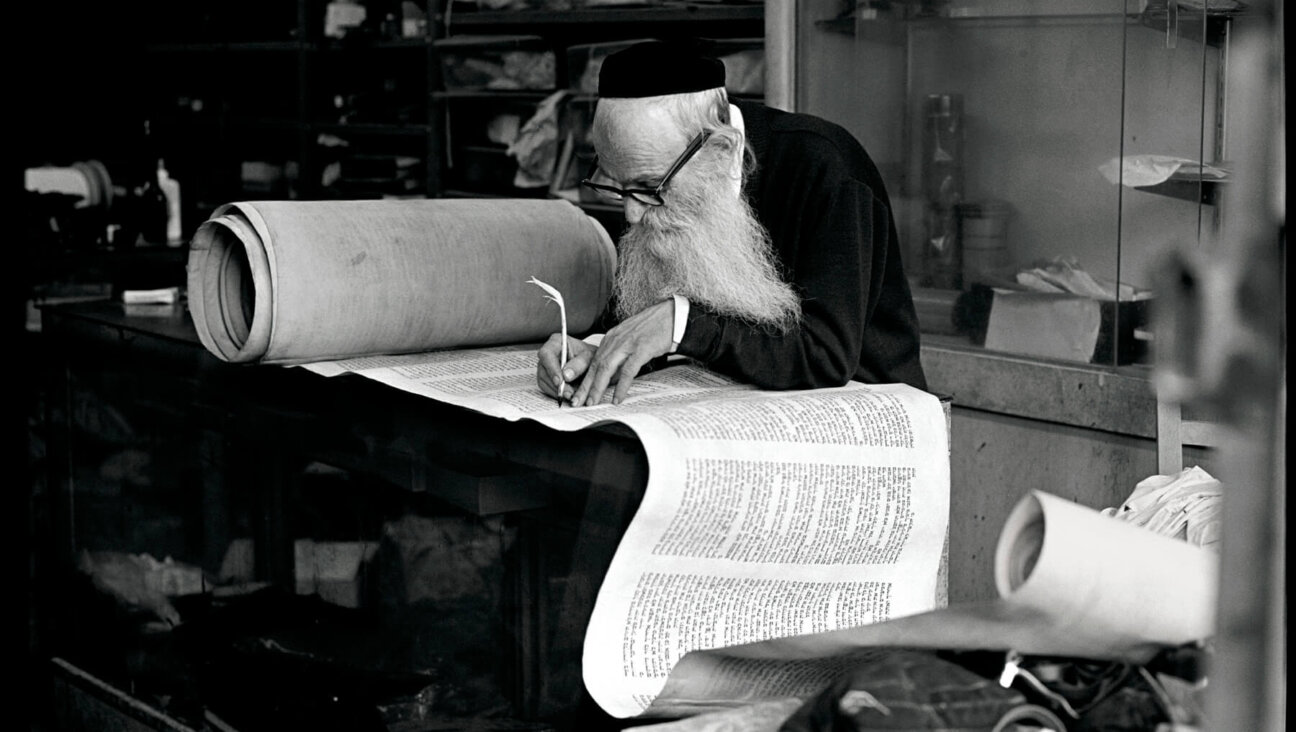

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Amos Elon, the Israeli journalist and author who died in Italy on May 25 at age 82, was described for decades as Israel’s leading public intellectual — the writer who, more than any other, explained Israelis to themselves and to the world. And yet, he spent his final years in self-described “exile” in Italy, despairing of Israel’s future. His passing received more notice in Europe and America than in Israel.

A Haaretz staff writer for five decades, Elon was one of the first Israeli journalists to chronicle the lives of neglected Sephardic immigrants in the 1950s and to describe the emerging challenges of Palestinian nationalism and the West Bank settler movement in the 1970s. He wrote the definitive biographies of Zionist founding father Theodor Herzl and of banking patriarch Mayer Rothschild. His best-known book, “The Israelis: Founders and Sons,” an international best-seller in 1971, permanently changed the way Israel was discussed at home and abroad.

“He was a journalist who was also a fine writer,” respected Yediot Aharonot columnist Nahum Barnea said. “In the Israeli journalism of the 1950s and 1960s, there was very little writing that combined well-informed opinion with literary grace. Amos was the best.”

Elon was also a secular, liberal-minded Western intellectual steeped in the mannered culture of his native Vienna and the socialist, freethinking Tel Aviv lifestyle of his childhood. The nationalist and religious trends that came to dominate post-1967 Israel left him disappointed and alienated.

In his last decades “he became distant,” Barnea said. “His outlook became more and more critical, and further from the Israeli mainstream. But at that point, he was no longer writing for an Israeli audience.”

Elon was born in Austria in 1926 and moved with his family in 1933 to what was then Palestine. As a teenager, he became involved with Tel Aviv’s literary and café society, where he came to the attention of Haaretz editor Gershon Schocken. Elon joined Haaretz as a reporter in 1951.

During the 1950s, he won acclaim for his coverage of Israel’s leading dramas, including the mass North African immigration and the traumatic 1952 schism in the kibbutz movement. Later he served as a correspondent in Paris and Washington, where he met his American-born wife. A posting in Bonn, the capital of West Germany, resulted in his first book, “Journey Through a Haunted Land: The New Germany,” published in 1967. It sympathetically depicted Germany’s struggles with its past, leaving many Israelis outraged.

The publication of “The Israelis” in Hebrew in 1970 and in English in 1971 marked the turning point in Elon’s career. His early writings celebrated the new Jewish state and its values. After the 1967 Six Day War left Israel in control of the West Bank and Gaza, he began writing probing critiques of Israel’s new triumphalist nationalism.

“The Israelis” depicted a Jewish state in transition, from the passionately ideological founding generation, led by Eastern European-born Zionist pioneers like David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir, to the generation of their Israeli-born children, pragmatic soldier-politicians like Moshe Dayan and Yigal Allon. The book’s other central theme was the obliviousness of founders and sons alike to Palestinian Arab frustration.

Elon’s depiction of generational transition profoundly affected Israeli thinking. “He put a name on a moment in history,” Barnea said. “It was a heroic book. It was assigned as reading in schools. You wouldn’t see schools today assigning a book like that.”

The book’s second theme, about Israeli shortsightedness toward the Palestinians, drew far less attention in Israel. But for readers abroad, especially liberal Jews, that was the book’s main message.

“It was extremely important to have Jewish Israelis writing about what was happening from a point of view that didn’t dismiss the Arab Palestinian community or the PLO itself,” said left-leaning American journalist Victor Navasky, publisher of The Nation magazine, which occasionally published Elon’s writing. “He was among the most thoughtful of those voices, and in a funny way, the easiest to accept. It was very important — particularly within the Jewish community — to have someone like him saying what he said.”

“The Israelis” pinpointed a transition not just in Israel, but also in Elon himself. His writing was shifting away from the patriotic outlook of his early work toward a deeply critical take on Israeli society. “If you read the earlier writings now, you would not believe it was the same Amos Elon,” Barnea said.

Lionized worldwide because of “The Israelis,” Elon left Haaretz in 1971 to lecture and to write books. A chance meeting in late 1973 with Sana Hassan, daughter of the Egyptian ambassador in Washington, resulted in a series of conversations that was published in 1974 as “Between Enemies: A Compassionate Dialogue Between an Israeli and an Arab,” causing a new sensation. He also wrote the Herzl biography during this period.

In 1978, however, Elon returned to Haaretz, turning out increasingly sharp commentary on the settlements and the West Bank-Gaza occupation. In 1986, he again cut his hours at the paper to focus on writing books and essays. He resigned from Haaretz formally in 2001, exactly 50 years after first joining it.

During the 1990s, he began spending much of his time at a second home in the Tuscany region of Italy. In a series of gloomy essays and reviews in overseas publications, mainly the left-leaning New York Review of Books, he criticized both Israelis and Palestinians but reserved most of his barbs for Israel.

During this period, too, he produced a stream of well-regarded books, including an acclaimed history of Jewish life in pre-Holocaust Germany, “The Pity of It All.” Tellingly, most were published first in English and only afterward in Hebrew. In 2004, he sold his home in Jerusalem and settled in Italy for good.

Before leaving Israel, he delivered what amounted to a farewell address in a Haaretz interview with reporter Ari Shavit. He said he was leaving because he was “disappointed” and at times “horrified” at what Israel was becoming, and he was tired of being a “lone voice in the wilderness.”

“It’s impossible to live here without feeling some unease,” he said. “And this unease grows the worse the situation gets.” In Italy, he said, he could live as “a pensioner sitting on a mountain and gazing at the gorgeous view.”

Still, he acknowledged, “I miss my friends in Israel very much.”

“Here is where I kissed a girl for the first time,” he said. “And what is a homeland if not the place where you kiss a girl for the first time?”

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected].