A Polish Priest’s Dream of Aliyah

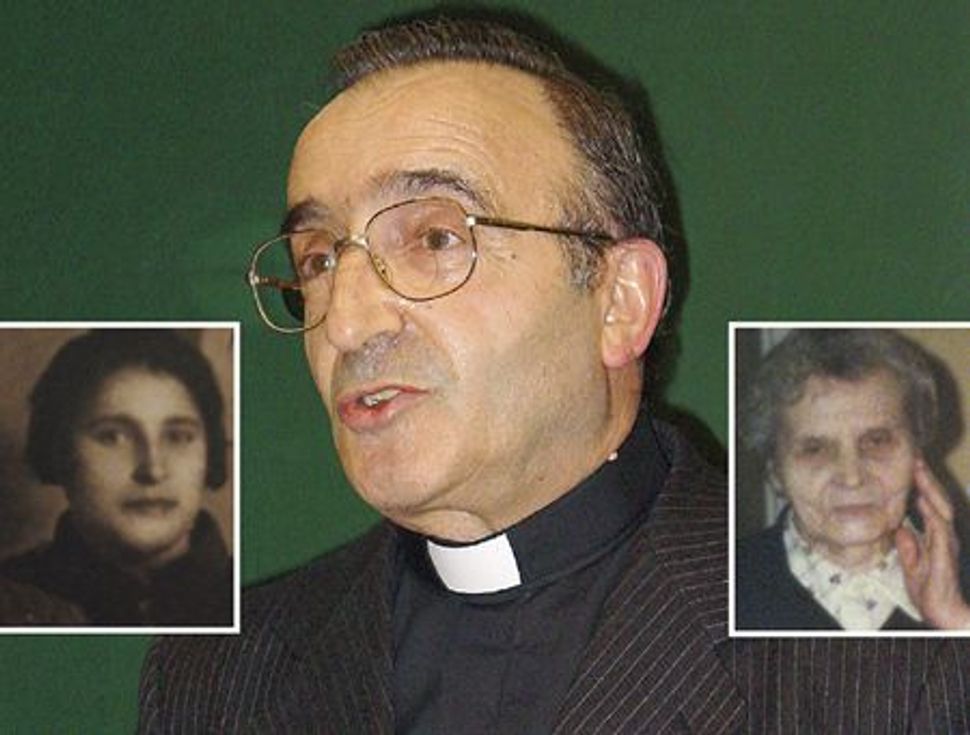

Son of Two Mothers: Father Romauld Jakub Wksler-Wasznikel was born a Jew to Batia Weksler, left, but was raised a Catholic by Emilia Waszkinelowa, right. Image by COURTESY OF R. J. WEKSLER-WASZKINEL

When Romuald Jakub Weksler-Waszkinel applied to immigrate to Israel as a Jew under the Law of Return last October, Israeli authorities delayed responding to his request for months.

Perhaps it was the priest’s white-band collar around his neck that had something to do with this.

Yet ultimately, Israel’s Interior Ministry did issue the 66-year-old Polish cleric, scholar and professor at Catholic University of Lublin a two-year residency visa. It was, it seems, an imperfect compromise with a priest who insists: “I am Jewish. And my mother and father were Jewish. I feel Jewish.”

Speaking through an interpreter during a phone interview, he said, “Going to Israel would be the return of the Jewish child who took the long way home.”

Born in 1943 in Nazi-occupied Poland, Weksler-Waszkinel did not know that he was Jewish until he was 35 years old, 12 years after he was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest. Nor did he know that his birth parents, both ardent Zionists, were murdered by the Nazis after entrusting his care to a Polish Catholic family to save his life. It took him 14 years after he learned he was Jewish to find his real name and the names of his parents. “So in a way, it took me 14 years to be born,” the priest said.

“My mother’s dreams went up in the flames of Sobibor,” he explained, referring to the death camp in Poland where some 260,000 Jews were murdered.

Weksler-Waszkinel is not the only one who grapples with a dual identity. Mark Shraberman, chief archivist at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum and research institute, said in an interview in Jerusalem that he receives many letters from Poles who are discovering that they are of Jewish origin. “They find out the truth when one of their parents is dying,” Shraberman said. He added that he recently received a letter from another Polish priest in a small town who just found out that he is Jewish.

But Weksler-Waszkinel, in seeking to rediscover his lost identity by immigrating to Israel, is taking his search for that identity further than most. Though he sought originally to become recognized by the government as a Jew under the Law of Return — the law that grants any Jew immediate Israeli citizenship — he pronounced himself “very satisfied” with his two-year visa.

Weksler-Waszkinel says that he plans to immerse himself in Jewish life. “I don’t know what that means; after all, I am a Catholic priest. But I will find out,” he said. “I thought, perhaps, I could be a volunteer at Yad Vashem as someone who survived the Shoah and who participates in the Christian-Jewish dialogue, which is so important.” He says that the first thing he will do is learn Hebrew.

Weksler-Waszkinel was born in the town of Stare Swjeciary — which was then in Poland but is now known as Svencionys in Lithuania — four years after the Nazi invasion of Poland started World War II. His mother, Batia Weksler, gave him as an infant to a Christian woman to save his life.

Emilia Waszkinel, his Christian mother, initially hesitated to take him because she and her husband, Piotr, risked death for hiding a Jew. Emilia was reportedly convinced to accept the baby in response to his Jewish mother’s plea: “Save my child, a Jewish child, and in the name of the Jesus that you believe in, he will grow up to become a priest.”

The couple raised the boy as their own child in Eastern Poland, where they lived after the war, without telling him that he was Jewish. The boy attended secular schools.

Perhaps because of this, his parents were shocked when, at the age of 17, Weksler-Waszkinel told them he planned to become a priest. His father tried to discourage him, saying he should instead become a doctor, and cried uncontrollably when visiting his son at the seminary. Weksler-Waszkinel felt enormous guilt when his father died shortly after this visit. Briefly, he considered ending his studies.

Even before discovering his Jewish background, Weksler-Waszkinel had harbored doubts about his true identity. The young man had been aware of the fact that he did not have the pronounced Slavic features of his parents. He had been called “a Jew bastard” by town drunks, so he asked his mother if he was Jewish. She assured him that he was Catholic. When he was 35, long after his ordination, he again inquired about his identity, and Emilia, weeping, told him about his Jewish mother.

Emilia told Weksler-Waszkinel that he had wonderful parents who were murdered by the Germans in the Holocaust and that she had saved his life.

“My head spun, and I asked her why she hid this from me,” the shocked priest wrote in a 1994 essay. “My heart was pounding as I thought that I had become a priest, something my mother said I would become.”

The priest had fulfilled the prophecy of his Jewish mother, a woman he had never known.

He felt he needed to confide in someone, so he wrote to Karol Wojtyla, who by then was Pope John Paul II but who had been Weksler-Waszkinel’s professor in Lublin. The pontiff responded, “My beloved brother, I pray so that you can rediscover your roots.”

Weksler-Waszkinel eventually traveled to Israel. There he met his Jewish father’s brother, who showed him a photograph of his parents. He realized that he resembled them. “My mother’s eyes are in me, my father’s mouth and the fears and tears of my brother,” he wrote in the 1994 essay.

Weksler-Waskinel’s uncle embraced him as a long-lost relative, but said that he could not understand how his nephew could be a priest and represent the church that has persecuted Jews for 2,000 years. The priest responded: “To really belong to Jesus means to love Jews. Jesus never betrayed me, and I will not betray him.”

Nevertheless, Weksler-Waskinel grapples with his tangled identity.

“His double identity is a problem for him that he struggles with all the time,” said Zbigniew Nosowski, a friend of the priest and editor of Weiz, a Polish-Catholic intellectual magazine in Krakow.

According to Michael Schudrich, chief rabbi of Poland, “Father Waskinel is incredibly honest in saying that he is Jewish, and he is also honest in not wanting to turn his back on the church.”

Some close friends grasp the enormity of the priest’s conflict. “He has an impossible task to find a place for himself,” said Stanislaw Krajewski who is a friend of the priest and teaches mathematics at the University of Warsaw. Krajewski said the 66-year-old priest has been “an uncomfortable presence” to some Jews and Christians because of his dual religious identity.

“He is very Jewish and very Christian,” said Hanna Krall, a prominent Polish journalist and novelist.

Weksler-Waszkinel says Poland will always be his fatherland and Israel will be his homeland.

The priest has devoted most of his academic life to writing about Jewish-Christian relations. He praises the reforms introduced by the Second Vatican Council, calling them “a radical change, a revolution.”

He is working to further improve ties between Christians and Jews, inspired by Pope John Paul II’s call for greater Catholic respect and understanding for Jews. When asked how Weksler-Waszkinel promotes ecumenism, Schudrich said, “When he gets up in the morning and breathes… his life’s message is that strong.”

According to a number of Polish intellectuals, Weksler-Waszkinel’s story brings Jews and Christians closer. “When he tells his personal story, he has tears in his eyes,” Krajewski said. “And audiences cry with him. It is a very sad story.”

Weksler-Waszkinel’s speeches to churchgoers and lay people point to the Jewish roots of Christianity and the enormous gap dividing the two faiths. He often criticizes the Catholic Church for not closing the gap between Jews and Christians. In our interview, he told me that Pope John Paul once said, “The New Testament finds its roots in the Old Testament,” and that what is significant is the word “finds.” Weksler-Waszkinel added, “Those roots have always been there, according to Pope John Paul, but for 19 centuries they were forgotten, and a Jew was considered the worst enemy.”

Weksler-Waszkinel’s application to go to Israel as a Jew under the Law of Return is clearly heartfelt. It also has a practical aspect. He said that getting Israeli citizenship would entitle him to benefits he needs to supplement his small pension of $900 a month. Under the two-year visa arrangement he has now accepted, those benefits will not be available. The priest is determined to immigrate, nevertheless, even with little money and just a two-year visa.

Experts doubt that the Ministry of the Interior, controlled by the ultra-Orthodox Shas party, would have granted Weksler-Waszkinel citizenship under the Law of Return.

In 1962, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled in a 4-1 decision against Jewish-born Oswald Rufeisen, a Carmelite monk known as Brother Daniel, who sought Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return. This was the first narrowing of the statute, which was basic to Israel’s identity from its founding in the wake of the Holocaust. Judge Haim Cohen, the single dissenter, noted that the Nazis sought to kill all those born Jewish, irrespective of their conversion from or rejection of Judaism. But the court ruled that the Law of Return did not apply to Jews who had embraced another religion.

Weksler-Waszkinel’s case for automatic Israeli citizenship seems to be stronger than that of Rufeisen in one respect: He could argue that he never did, in fact, “embrace” another religion. Unlike the Polish-born Carmelite monk, who converted as an adult to Catholicism after finding shelter from the Nazis in a convent, Weksler-Waszkinel never consciously chose to leave Judaism for another faith. He argues that he considers himself a Jew who was raised from infancy as a Catholic without being informed of his true identity.

“The court fight would be lengthy and complicated, and he decided to avoid it,” said Schudrich, who is helping the priest relocate to Israel.

“He wants to be in a place where he can see a full, rich Jewish life,” Schudrich said of Weksler-Waszkinel’s need to fulfill his dream to live in Israel. “He has this inner longing to be in a place that is surrounded by the culture of his ancestors.”

Contact Donald Snyder at [email protected].