Part V: Writing in My Father’s Footsteps

Shiva for Ayah: Lt. Ayah Feldman was killed on a hill overlooking Lebanon. Image by COLLECTION OF NORM SCHUTZMAN

After the battle at Tamra, my father’s commander, Norm Schutzman, moved the men of B-Company up to the coast North of Haifa for more training. In late fall, Schutzman received orders that the entire 7th Brigade, including his company, was to clear the Galilee of Arab troops to the Lebanese border.

Schutzman’s company’s assignment was to take Mount Meron, the highest mountain peak in Israel. Arriving in Safed, Schutzman went to Meron with a platoon commander to devise a strategy. It quickly became clear that his men would have to gain control of the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, which is situated on Mount Meron and had acted as a military fortress for Arab troops.

Back in Safed, Jack Lichtenstein, commander of the 72nd Battalion, briefed Schutzman: A guide would lead his company behind enemy lines at night for a daylight raid of Shimon’s tomb. That same afternoon, however, orders came from David Ben-Gurion that the operation was to be canceled; Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat, and the United Nations mediator in Palestine, had been assassinated by Lehi, an extreme right-wing Jewish group. Ben-Gurion felt that, from a diplomatic standpoint, the timing of the attack would be wrong. For weeks, Schutzman and his men waited idly.

Six weeks later, Schutzman received the order to take Mount Meron. To sneak behind enemy lines, Company B left Safed at nightfall, and met the guide who took them into the fields. Marvin Libow, a soldier who fought alongside my father, recalled, “We got out of the buses and it was pitch black. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.” Schutzman recalls that the guide took them across a bridge leading to the base of the steep climb up toward Shimon’s tomb. The plan was to blow the bridge to prevent any counterattack, and sure enough, a half-hour later, around 1 a.m., the bridge was blown.

Shiva for Ayah: Lt. Ayah Feldman was killed on a hill overlooking Lebanon. Image by COLLECTION OF NORM SCHUTZMAN

Reacting to the explosion, Arab forces at the tomb began to fire Very pistols into the sky to see what was happening on the hill below. The flares lit up the landscape, showing Schutzman and his men that their guide had actually gotten them lost; they were on the wrong side of the mountain! By the light of the magnesium sky, they were able to reposition themselves to attack at daybreak.

At dawn, the attack began. The ascent to Shimon’s grave was steep, with no leaf cover and strewn with rocks. The tomb was a concrete fortress, and Schutzman recalled that the only way in would be to focus their artillery on a few vulnerable windows. Libow remembers that during the fight, one man, Shmuel Daks, was killed. Daks was an Austrian-born Englishman who was fighting alongside Libow. He couldn’t get a good shot, so he rose from his crouched position to get a better view. Libow remembers hearing the sound of Daks’s weapon jamming, then a burst of machine gun fire from the Arabs above, in the fortress.

The next moment, Libow was digging rock fragments out of his face, calling out, “Daks, are you all right?” Libow, finally able to see, saw that Daks had stopped breathing. Not knowing what to do, he ran over to his sergeant, Jack Franses. Libow yelled, “Jack, Jack! Daks is dead!” Franses snapped back at Libow, “Shut your f***|ing mouth!” Libow, green in battle, didn’t understand that the loss of morale created by word of casualties could be deadly.

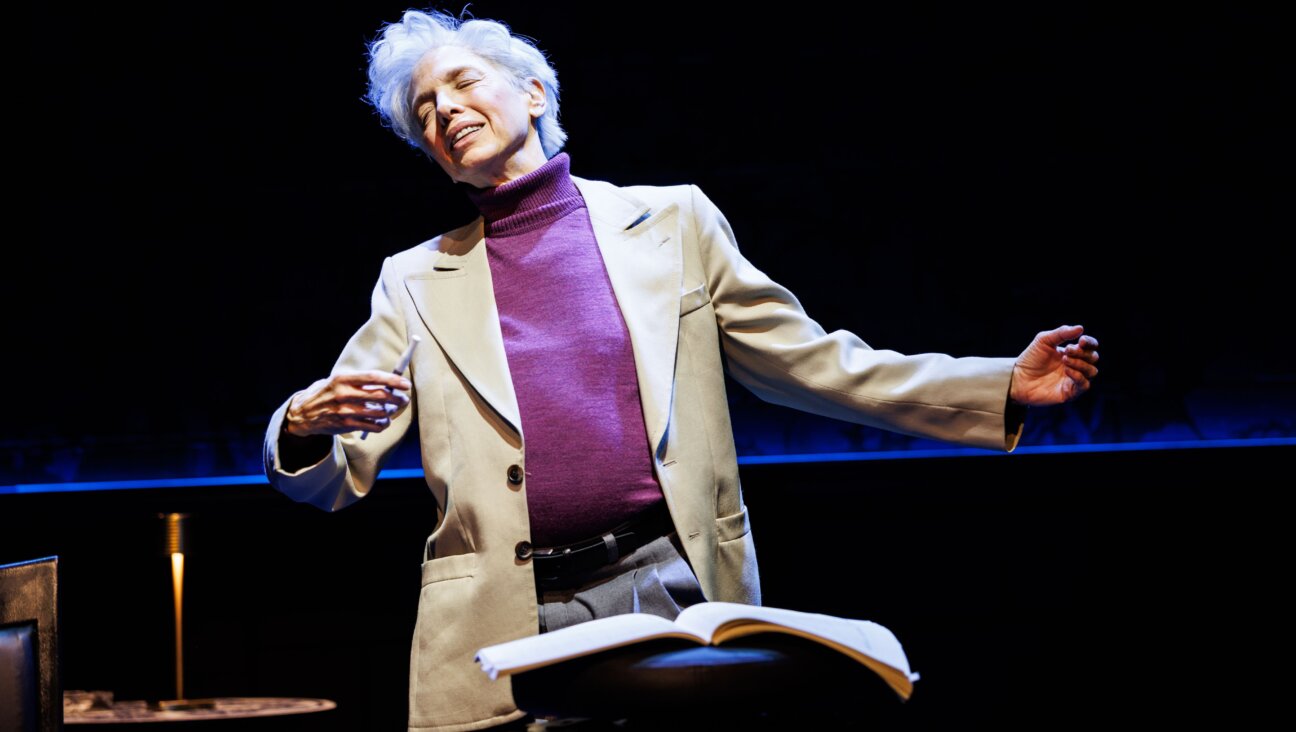

Schutzman and his men, including my father, finally took the tomb. It took the rest of the 72nd Battalion two to three days to sweep the rest of the Galilee. From Meron, Company B went through Jish and Sasa, and from there north to the Lebanese Border. The next day, they spread out on a hill overlooking Lebanon. Schutzman remembers that they could have easily swept through all of Lebanon, but Ben-Gurion made it clear that his men were to stop at the border. After instructing his platoon commanders where they should place their men, Schutzman was visited by his friend Lieutenant Ayah Feldman at company headquarters.

Feldman wanted to show Schutzman something special: Away from the platoon, on the other side of the mountain, was an incredible view of Lebanon. Schutzman recalls that after the two friends crossed a ridge, Feldman ran forward and crouched down behind a large rock. Schutzman followed and crouched down next to him, pulling out his maps to see where they were. As the two took in the beautiful vista, Schutzman recalled suddenly hearing shots ring out. He looked to his left to find that Ayah, his friend and confidant, was dead.

As Schutzman turned his attention, he saw a swarm of Arab troops coming directly toward him. Schutzman began to scream for help, but knew he was too far from his men for anyone to hear: “I knew this was the end. People say that every soldier in a foxhole prays to God. I am not a very religious person. It never occurred to me to pray to God. I grabbed Ayah’s pistol and my own pistol and started to fire. My only thought was that my mother wouldn’t recognize me. A few weeks earlier, a scout of mine had been completely mutilated by an Arab.”

As the Arab troops descended on Schutzman, he heard some yelling, and looked behind to see his company coming up over the ridge to his defense. After some fighting, his men were able to save Schutzman and to recover Feldman’s body. At the time, Feldman was engaged to be married.

Later, wracked with sorrow, Schutzman went to visit Feldman’s parents while they were sitting shiva. Feldman’s father was president of the Palestine Electric Company at the time, and Schutzman recalls him crying: “Dear God, why didn’t you take me? I’ve had a life and Ayah’s life was all before him.” Schutzman said: “It often crosses my mind — if I had flopped to the left of Ayah, rather than the right, Ayah would have a wife, children and possibly even grandchildren that would be his pride and joy. I would be the one lying in a grave on Foulk Road.”

It wasn’t until 1998 that Schutzman discovered how his life was saved. Irv Matlow, from Toronto, wrote to Schutzman to verify his account of his war experiences. Matlow had been assigned to Company B as a signalman while they swept the Galilee. While Schutzman and Feldman were being attacked, Matlow had received a call from Jack Lichtenstein, who wanted to speak to Schutzman. Not able to find Schutzman, Matlow went looking for him, saw the advancing Arab troops and radioed back to the men of Company B to come to his aid.

Since Schutzman discovered that Matlow had saved his life, the two have become close friends, and they and their wives meet every year at Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Meron was the final battle my father fought in before the 1949 armistices were signed. My father stayed in Israel for four more years, living on the newly formed Moshav HaBonim, which still exists just south of Haifa. My mother recalls that my father told her the moshav comprised South African, English and American Jews, and that for four years, my father worked as a tractor driver and took care of the cows. Eventually, my father returned to the States. A staunch Zionist, but not religious, he felt that it was time for him to make a break with his Orthodox family, and he made a trek to California, where he eventually married my mother, had four children and spent 30 years working for IBM.

My father passed away at the age of 66, when I was 18. For those 18 years I loved him more than anyone in the world. Being a father at a late age made him gentler than he had been with my older brothers and sisters. Instead of teaching me about sports, he taught me the joy of exotic food and began what has become my lifelong passion for film.

I remember hearing stories of “tough guy” Jack Kesselman from my older brothers and sister. I also remember after my dad passed, my father’s half-brother Bernie showed us where he, my father and my Uncle Wally were “drug up” in the Bronx, and regaled us with the story of my father “the hero,” who chased down and scared the living daylights out of the tough kids in the neighborhood who stole his religious half-brothers’ yarmulkes during a game of stickball. I, however, rarely saw glimpses of this Jack.

Since I began writing these pieces, I have met men who knew my father, and I have come into contact with relatives on my father’s side who I never knew existed. I have seen photos of my father as a young man that I have never before seen, with friends and relatives he loved, people I never knew. His cousin, Iris (now in her 70s), and her husband recently came over to my sister’s home for dinner: It was the first time our families had met. I asked Iris why my father and she never kept in touch after he moved to California. Iris simply explained, “That was just Jackie’s way.”

A few months earlier, Iris had sent me a letter that my father had written to her after her mother, Bessie Kesselman, the woman he had loved like a mother, passed away. Dated December 2, 1951, it was postmarked from Israel, and when I read the handwritten letter, I cried. The letter was so beautifully composed, so deeply felt, that at first I couldn’t believe it was written by my own father. I never knew Jack Kesselman as a writer. After stepping through some of his footsteps and reading what he wrote, I can only hope that one day I might become half the writer he was.

Jonathan Kesselman is the youngest son of Jack Kesselman. Jack is survived by his daughter Beth, his sons Joshua, David and Jonathan, and his grandson Jacob Cole Kesselman.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO