Jewish Organizations Should Spare the Change

Innovation, we are often told, is the great savior. It will remake Detroit, cleanse the atmosphere and educate every child.

Years of steady drops in the membership rolls and donor bases of many American Jewish institutions, from national advocacy organizations to community federations, have led many to conclude that innovation is also the key to solving the problem of participation in American Jewish life. Money and support should be given to young, creative Jews, who will manage new programs free of the institutional baggage that prevents the engagement of their peers.

The effect of this thinking is evident nearly everywhere one looks on the Jewish communal landscape. Avi Chai fellowships in the hundreds of thousands of dollars are directed to young “thought leaders” unconnected from established Jewish organizations. Natan grants $75,000 to “independent communities of young Jews” creating “new forms of Jewish religious and communal life.” And dozens of small Jewish organizations with a handful of staff and supporters have been founded in the past decade. According to a report recently produced by Jumpstart — a group that bills itself as “a thinkubator for sustainable Jewish innovation” — this “innovation ecosystem” has constituted, altogether, a $500 million investment.

Of course, the decline in traditional institutions is hardly a uniquely Jewish phenomenon. A decade ago, sociologist Robert Putnam demonstrated in his widely cited book, “Bowling Alone,” that Americans’ involvement in a variety of civic institutions — from mainline Protestant churches to Lions clubs — had been on the wane for decades. More recently, a March release from the General Social Survey reported that American confidence in nearly all social institutions has fallen since 1976. It is only natural that similar declines have been felt in American Jewish institutions.

The reasons for this trend were catalogued in two reports produced during the past few years by researcher Anna Greenberg. She wrote that for many young Americans “pursuing the American Dream simply means ‘doing whatever I want’” and that “institutional Jewish life appears virtually irrelevant” to them. The source of this sentiment is a feeling that institutions are unable to encompass young people’s “multiple identities,” which cannot be contained in a single way of thinking.

Like their non-Jewish peers, young Jews’ distaste for institutions grows from the demands institutions, by necessity, make on their allegiances — to one country, say, or to one identity. To Jumpstart, this means communal organizations must appeal to young Jews’ “highly individualistic” web of “non-exclusive relationships and connections,” many of which are only partially or even secondarily Jewish. The organizations that thrive will be those best able to accommodate this new way of thinking.

Now, it is certainly true that Jewish communal organizations must be flexible in order to meet new challenges and opportunities. There are many ways they can be made to work better. All, no matter how large or old, should feel a need to justify themselves to a changing world. To attract young people to work for them, they will also have to make themselves somewhat receptive to their wishes.

But in order for Jewish institutions to offer something more to young people than the kind of superficiality for sale at American Apparel, they must hold fast to their institutional identities. Rather than pretending that they can be all things to all people, they should emphasize their commitments to particular ideas and demonstrate the long histories of those commitments. Instead of revising their mission statements, institutions should articulate them more forcefully, embracing the demands they make of those who belong to them.

In the end, the best kinds of institutions are those that ask the most of us. This is true in terms of both the effort we put into them and the difficulties we face in aligning our ideas about the world to those embedded within them. Such is the trade-off. As David Brooks has put it, “Institutions do all the things that are supposed to be bad. They impede personal exploration. They enforce conformity. But they often save us from our weaknesses and give meaning to life.”

Jewish institutions are too important to adapt themselves to the whims of 20- and 30-somethings. For them and for all of us, the next great Jewish idea could be a very old one: Institutions are valuable.

Matthew Ackerman is a member of the Professional Leaders Project.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

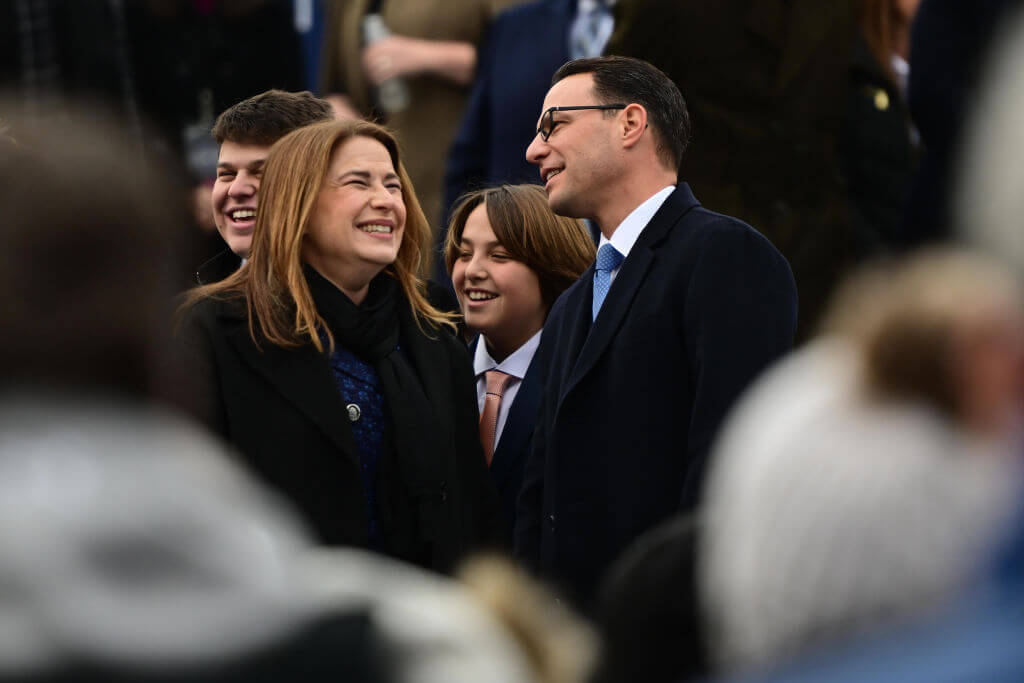

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture How an Israeli dance company shaped a Catholic school boy’s life

-

Fast Forward Brooklyn event with Itamar Ben-Gvir cancelled days before Israeli far-right minister’s US trip

-

Culture How Abraham Lincoln in a kippah wound up making a $250,000 deal on ‘Shark Tank’

-

Fast Forward Marco Rubio sits down with Michael Benz, Jewish former Trump official with an antisemitic online persona

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.