Secret FBI Files Reveal Hoover’s Obsession With Militant Rabbi

The FBI closely monitored the militant Jewish Defense League and its fiery leader Rabbi Meir Kahane out of concern that the group’s protests and violent action could hurt fragile diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, according to government documents obtained by the Forward.

The documents, many of them labeled “confidential” and partly redacted, reveal a preoccupation with the JDL shared by the bureau and its infamous director J. Edgar Hoover, starting at least as early as 1970. The longtime FBI director ordered aggressive infiltration and surveillance of the group, while reporting even seemingly benign details to the Nixon White House.

The JDL, founded in 1968 to advocate armed Jewish self-defense against street crime, took the slogan “Every Jew a .22.” Later the organization took up the cause of Soviet Jewish emigration, advocating violent attacks on Soviet diplomats that landed several adherents in prison.

Kahane, an Orthodox rabbi in Brooklyn and the JDL’s national chairman, was closely monitored as a “priority 1” on the bureau’s security index. The FBI was especially concerned about the JDL’s harassment and potential attacks on Soviet diplomats and installations at a time when President Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, were promoting “détente” with Moscow. In early 1971, Hoover regularly sent “priority” memos on Kahane to Kissinger, Secretary of State William Rogers, CIA Director Richard Helms, Attorney General John Mitchell and the head of the secret service.

“The FBI surveillance of the JDL was the worst-kept secret in New York City,” said Yossi Klein Halevi, a senior fellow at the Shalem Center and a former member of the JDL. “I’m actually glad the FBI did their job because the JDL was a dangerous group.”

Hoover’s memos detailed Kahane’s arrests on charges of riot, unlawful arms possession, resisting arrest and disorderly conduct. They also reported on the rabbi’s attempts to force meetings with senior American officials, as well as his plans to harass Soviet interests and derail strategic arms talks with Moscow.

In 1971 Kahane moved to Israel, where he quickly established the anti-Arab Kach Party. He was slain by an Egyptian gunman in 1990, during a return visit to New York.

“I remember we had pictures of potential FBI informants in the JDL offices,” said New York State Assemblyman Dov Hikind, a former Kahane lieutenant who now represents the Brooklyn neighborhoods where the militant organization was born.

Several JDL members filed a lawsuit in 1971 claiming that the authorities had unlawfully wiretapped JDL communications. In recent years, the organization’s dwindling followers have suggested that the government may have had a hand in the respective 2002 and 2005 jailhouse deaths of two JDL leaders convicted of plotting attacks against Arab and Muslim targets in Los Angeles: Irv Rubin, Kahane’s hand-picked successor, and Earl Krugel.

Hikind said it was “amazing” to think of “the level of resources the government used to destroy the JDL and how Kahane and a bunch of kids got them so excited.”

“I mean 99% of our activities were just rallies and demonstrations,” Hikind added.

Perhaps, but then it was the other 1% that put the JDL on the map and likely attracted the attention of the FBI.

In September 1969, the president of the United Nations Security Council revealed that six Arab missions at the U.N. had received telegrams from the militant Jewish group threatening revenge for terrorism. The next year, about 50 JDL members took over the Park East Synagogue opposite the Soviet mission at the U.N. and unfurled banners decrying the plight of Soviet Jews. A few days later, six JDL members stormed the offices of two Arab propaganda agencies in New York, severely beating three Arab men and sacking the place.

By then, the FBI had already begun investigating the militant group — and Hoover was already demanding results.

In a September 15, 1970, letter to the FBI’s New York office in charge of the probe, Hoover criticized the slow progress of the investigation, urged the recruiting of informants and requested that reports on the topic be transmitted as “instant communication.” Around that time, the JDL’s activities took a potentially more deadly turn when two of its members were arrested in an alleged plot to hijack an Arab airliner at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport.

In a December 21, 1970, form sent by Hoover to the director of the secret service regarding presidential protection, Kahane was listed in the category of “subversives, ultra-rightists, racists and fascists.” Hoover offered a similar recommendation on several occasions, warning of potential terrorist activities.

Over the years, reports have surfaced claiming that Kahane and the JDL were used by the FBI and the Mossad to create tensions between United States on the one hand and Arab countries, leftist groups and Soviet interests on the other. In one of the numerous bureau accounts of Kahane’s public speeches, the FBI quotes the rabbi as saying that prior to his JDL days he had served as a government agent, helping to infiltrate anti-Vietnam groups in the 1960s, but also claimed to have severed all relations with the American government.

The documents make plain the degree of infiltration of the JDL by the bureau, which closely tracked the group’s anti-Soviet activities, amateurish training camps and hijacking plots.

In addition to monitoring Kahane’s home, phone, bank accounts, back-and-forth trips to Israel, and his travels to Europe and Canada, the bureau dispatched agents and informants to the rabbi’s speaking engagements around the country. They reported scrupulously to Hoover and, after his death in 1972, to his successors on Kahane’s moves and speeches, including his anti-communist rants and militant calls for Jews to organize and defend themselves against leftists and blacks in particular.

After Kahane moved to Israel, the FBI’s office in Tel Aviv kept close tabs on his political activities — most notably the creation of Kach, as well as his convictions for plotting attacks on Arab terrorists and Soviet officials. But the bureau’s interest slackened in the late 1970s, and surveillance of the JDL and Kahane was suspended in 1976 and 1977, respectively.

The JDL was linked to the murder of an Arab-American activist in 1985, but it is unclear whether the incident drew renewed attention from the FBI.

Kahane was elected to the Knesset in 1984. But his Kach Party, which advocated the mass transfer of Arabs, was banned in the late 1980s from taking part in future elections after the Israeli government ruled that its platform contained racist incitement. In 1994, Kach was designated as a terrorist group by Israel and the United States after one of its members, Baruch Goldstein, killed 29 worshippers in Hebron.

Following a speech in New York, on November 5, 1990, Kahane was gunned down by an Egyptian militant named El Sayyid Nosair. Law-enforcements authorities concluded Nosair was a lone gunman. But he was convicted of firearms possession rather than murder because of a lack of evidence.

It was only after the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993 that investigators eventually translated Arabic documents they had initially found in Nosair’s possession. The documents offered clues into future terrorist plots, including the 1993 World Trade Center bombing planned by a cell headed by blind Sheikh Omar Abdul Rahman.

Nosair was then convicted as part of the wider terrorist plot and eventually of Kahane’s murder. The FBI files on the Kahane murder have not been released.

Hikind argued that if the government had dedicated as much resources to tracking Islamic terrorism as it had to the JDL, law enforcement authorities might have been able to stop future terrorist attacks, including the ones on September 11, 2001.

“When Kahane was killed, the first thing the NYPD did was to say that his murder had no connection to other groups,” Hikind said. “But if they had translated some of the documents they found in [Nosair’s] possession, they would have drawn connections to radical groups.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

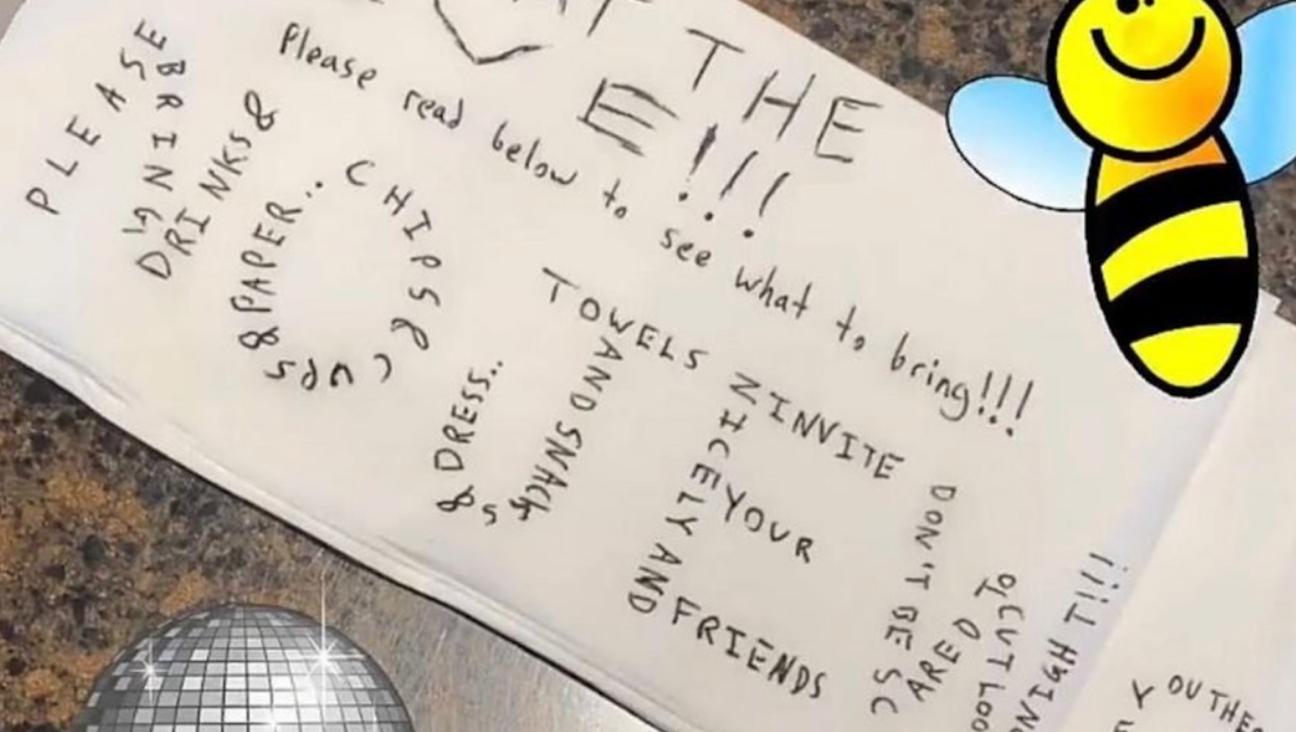

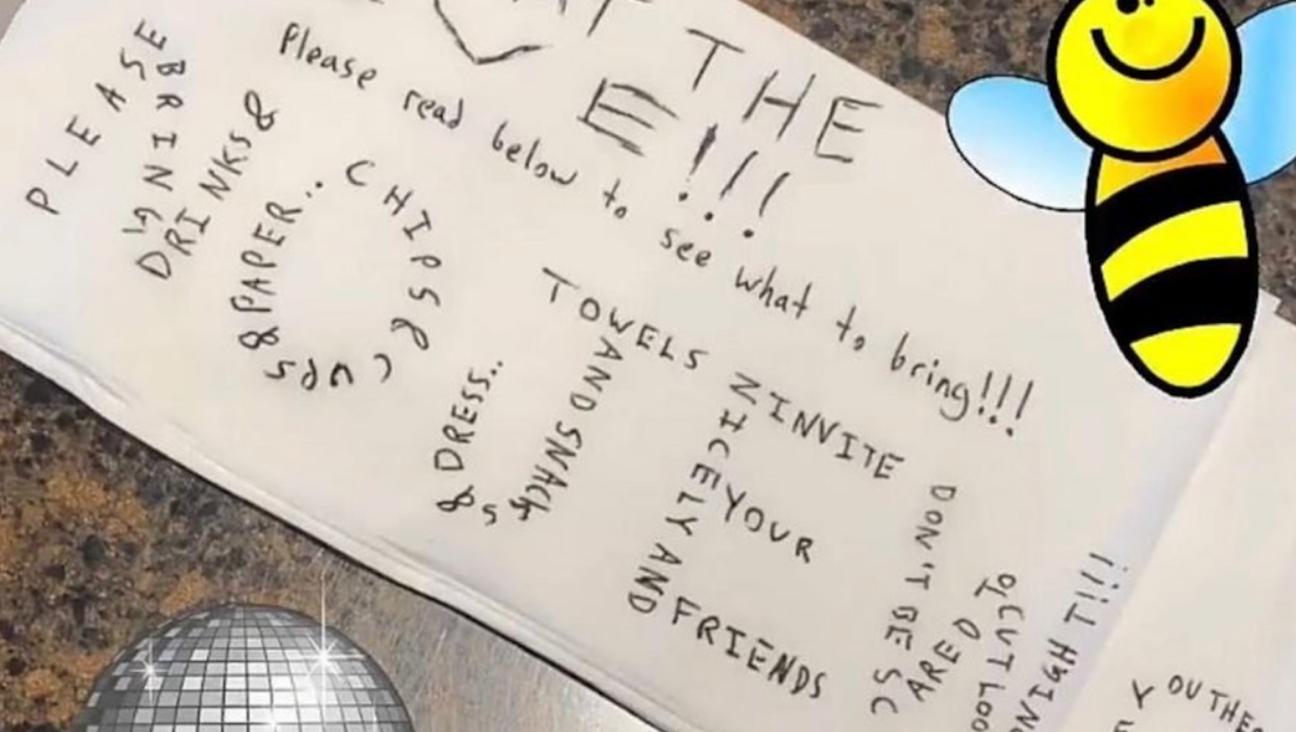

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture In a Haredi Jerusalem neighborhood, doctors’ visits are free, but the wait may cost you

-

Fast Forward Chicago mayor donned keffiyeh for Arab Heritage Month event, sparking outcry from Jewish groups

-

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

-

Fast Forward Latvia again closes case against ‘Butcher of Riga,’ tied to mass murder of Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.