In Search of Religious Rationality, Dalai Lama Visits … the Mideast

JERUSALEM –– The Dalai Lama, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and exiled leader of the Tibetan people, paid his fourth visit to Israel last week. The self-styled “simple Buddhist monk” sold out speaking engagements, sparked a small controversy within the Israeli government and, just as a Hamas-led parliament was about to be sworn in, met with Palestinian peace activists.

“My main purpose in coming here is to promote human values and religious harmony,” the 70-year-old leader said. “If we understand the value of other traditions, then we can develop mutual respect and mutual understanding.”

Previous visits to Israel by the Dalai Lama have been controversial, and this one was no exception. The leader is a popular figure among Israelis — his latest visit was reported on daily by all the major newspapers — a fact attributable, at least in part, to the Israeli penchant for travel to the Far East. Hebrew is spoken regularly on the streets of Dharamsala, India, seat of the Tibetan government in exile.

Many travelers return to Israel with an interest in Buddhism.

Within the Israeli government, however, the Dalai Lama can be a problematic figure. His 1999 meeting with then-Knesset speaker Avraham Burg and then-education minister Yossi Sarid elicited strong protests from the Chinese government, which at the time was negotiating a weapons purchase from Israel. This time, the Chinese regime, now a significant buyer of Israeli weapons, argued that Israel should not have even let the Dalai Lama into the country. As a result, no government official met with him. China has occupied Tibet since 1949, and the Dalai Lama has been in exile since 1959.

None of this fazed the Tibetan leader — or so he said. “It’s not a problem,” he said when asked about the governmental snub. “Wherever I go, I make clear I do not want to create inconvenience to concerned officials or concerned governments.” Asked about the Chinese Embassy’s complaint to the Israeli government, the Dalai Lama said: “The people in the embassy are carrying out their mission very loyally. If you have an opportunity to meet some of the Chinese officials privately and personally, they may express a different opinion.”

The flap with China was only one distraction from the Dalai Lama’s ostensibly “spiritual” visit. Given that his arrival coincided with the installation of the new Hamas-led Palestinian Parliament, he was asked many times during the week about his view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. On more than one occasion, he handled reporters’ questions with the dexterity more commonly associated with politicians than with monks. Asked whether Israel should negotiate with Hamas, for example, he replied: “Let us wait and see what they do. Hamas got the majority in the elections, so we must respect the results of the democratic election. But I want to take this opportunity and make my appeal to Hamas that the violent way will not achieve what you want.”

When asked whether the Tibetans had more in common with Jews or with Palestinians, he diplomatically replied that “making comparisons [is] always difficult.” He added that while in theory, violence could be legitimate “if the motivation is genuine interests of people and goal is something beneficial,” in practice, “every time you commit to violence there is counter-violence. Through violence you will not receive a satisfactory result.”

Most importantly, the Dalai Lama added, “one shouldn’t use the name of religion” as part of a political conflict. “Once the name of religion is used, it touches human emotion. And when things become related to emotion, there is no room for reason.”

At the same time, the Tibetan leader stressed that spiritual and political concerns are not separate. “We all have the potential of warm-heartedness, which helps us survive threats through childhood. After birth, we immediately approach our mother’s breast, taking milk, and feeling love and closeness. That is the basis of our survival. Later, though, we neglect our basic values. We involve something else, like religious faith, political interests or economic interests, and our basic human value remains in a dormant state. If we were to carry a more realistic handling of human feeling or human warm-heartedness, I think many problems can be reduced if not eliminated.”

Such universalist messages, rather than any particular political program, were the focus of three sold-out lectures in Tel Aviv and Beersheba. The talks focused on such topics as “universal responsibility” and “training the mind.” Even then, however, the Dalai Lama refrained from the clichés one often hears in connection with such topics. At the first lecture in Tel Aviv, for example, one audience member offered to give the leader a blessing. Laughing, as he did in response to many of the questions put to him, the Dalai Lama responded, “Thank you, but I am skeptical.

“I am one Buddhist who very much emphasizes the importance of human intelligence rather than blessing or prayer,” he said. “To those people who want some kind of blessing from me, I always tell them that the blessing must come from within.… And action is more important than prayer.

“The best way is to talk, to approach with a more realistic way the new reality,” he said. “My Israeli friends have long explanations about past experiences and difficulties, including the Holocaust. Then when I listen to the Palestinians, they also have a lot of things to complain about. We must try to find a solution through dialogue on the basis of mutual respect.” Ironically, the Dalai Lama’s planned meeting with Palestinians in Bethlehem, coordinated by the Palestinian NGO Holy Land Trust, had to be canceled for what the group called “an atmosphere [that] did not provide for a clear visit. And at the same time that the Dalai Lama led a discussion on nonviolence, Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh was nominated to be the new Palestinian prime minister, and Israel’s Cabinet voted to halt the transfer of funds to the Palestinian Authority, effective immediately.

The occupation of the Dalai Lama’s own country is perhaps the one global conflict even more intractable than the one in the Middle East. Since 1949, more than 1 million Tibetans have died at the hands of the Chinese occupation, and thousands of monasteries have been destroyed. Tales of monks and nuns being tortured, of widespread sexual abuse and of such horrific acts as children being made to kill their parents all have been verified by international human rights groups. While the world’s attention is often focused on Israel’s settlers, who now number about 400,000, more than 5 million ethnic Chinese have now been settled in Tibet. As a result, Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, now has more Chinese residents than it has Tibetans. Given China’s position of prominence on the world stage, however, criticism from the United Nations, Europe and United States has been muted and even nonexistent.

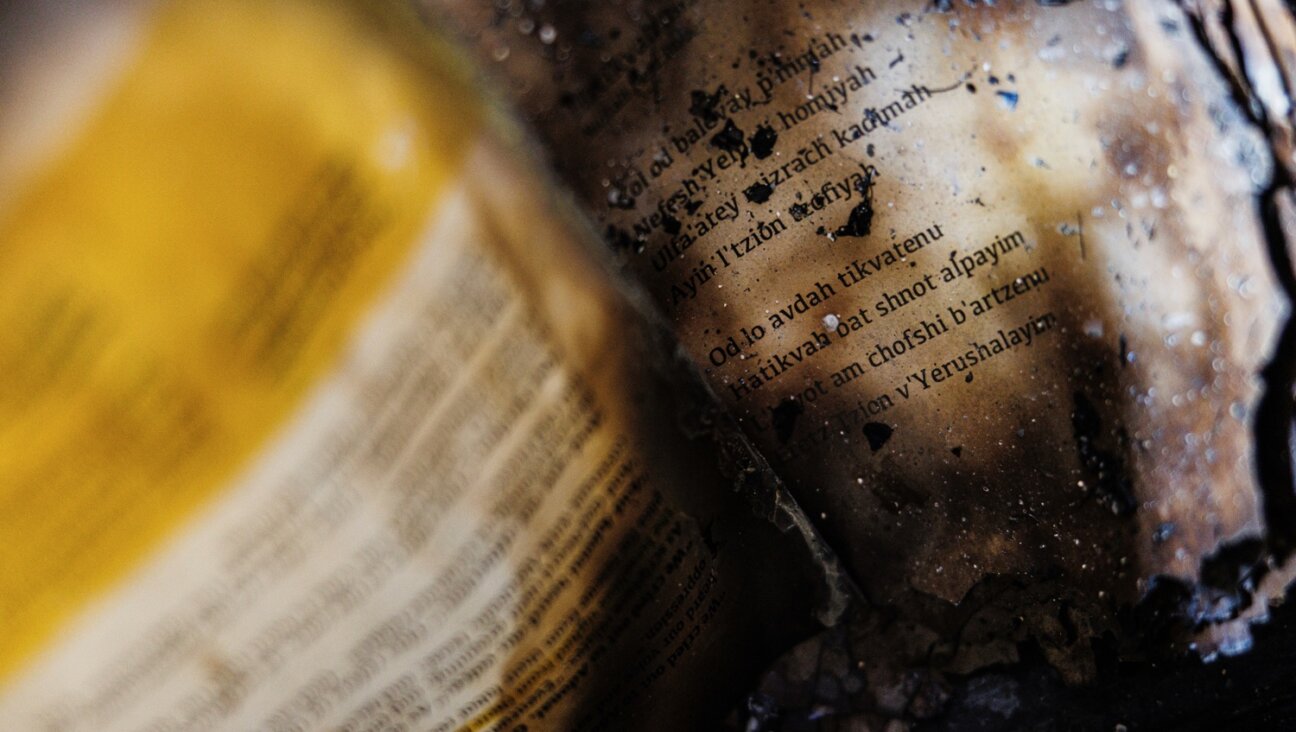

As a result of the Chinese occupation and Tibetan exile, the Dalai Lama and his associates have long sought to learn what he called “the Jewish secret — how to keep your spiritual tradition alive through so many centuries.” This campaign has included cultural exchanges, visits by Tibetans to Jewish summer camps and community centers, and many meetings with rabbis, which includes the series of conversations that became the subject of the book and film “The Jew in the Lotus.”

Notwithstanding Tibet’s tragic political history, such best-selling books of the Dalai Lama as “The Art of Happiness” and “The Power of Compassion” generally focus on how to attain happiness in everyday life, much as his public talks in Israel focused less on the political than on the personal. “The very purpose of life is to be happy,” he says in one book. “And if you want to be happy, practice compassion.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

-

News ‘Whose seat is now empty’: Remembering Hersh Goldberg-Polin at his family’s Passover retreat

-

Fast Forward Chicago man charged with hate crime for attack of two Jewish DePaul students

-

Fast Forward In the ashes of the governor’s mansion, clues to a mystery about Josh Shapiro’s Passover Seder

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.