Neither and Both

l An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature: Two Centuries of Dual Identity in Prose and Poetry

Volume 1: 1801-1953

Volume 2: 1953-2001

Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer

M.E. Sharpe, 1,376 pages, $225.

The ideal anthology is now, one would think, impossible. Not aiming for the compleat condition as established by the encyclopedia (18th century), biographical dictionary (19th century) or, today, by the googolplex Internet, an anthology’s purpose was, historically speaking, to establish a canon, to assert a primary or mainstream historical narrative that would encompass diffuse and indirect efforts in the literary arts. This hope, revivified early in the 20th century for various commercial or academic (as opposed to scholarly) purposes, was unknown to the Greeks, whose first-century BCE “Anthology” was the unconscious Adam of its race, and so achieved perhaps unintentional posterity. The Anthologia Graeca, as it is now known, otherwise referred to as the Palatine Anthology, was the first volume compiled, by one Meleager of Gadara, under the “Anthology” rubric; the Greek word means “garland,” or “bouquet.”

More than a mere formal progenitor, though, this book’s very making was the model for the Total Library that is the Internet, in that its collocation was made colloquy, a discussion between generations and cultures, with the subsequent efforts of later editors, such as Agathias and Maximus Planudes. What ultimately resulted was an ideal of Grecian art, of Grecian poetry, in its origins and development. What has come down to us, then, is the fictive or fictionalizing idea of a canon, of “the canon” — the Western humanist narrative, it might be called, which, despite all evidence to the contrary, serves us still today.

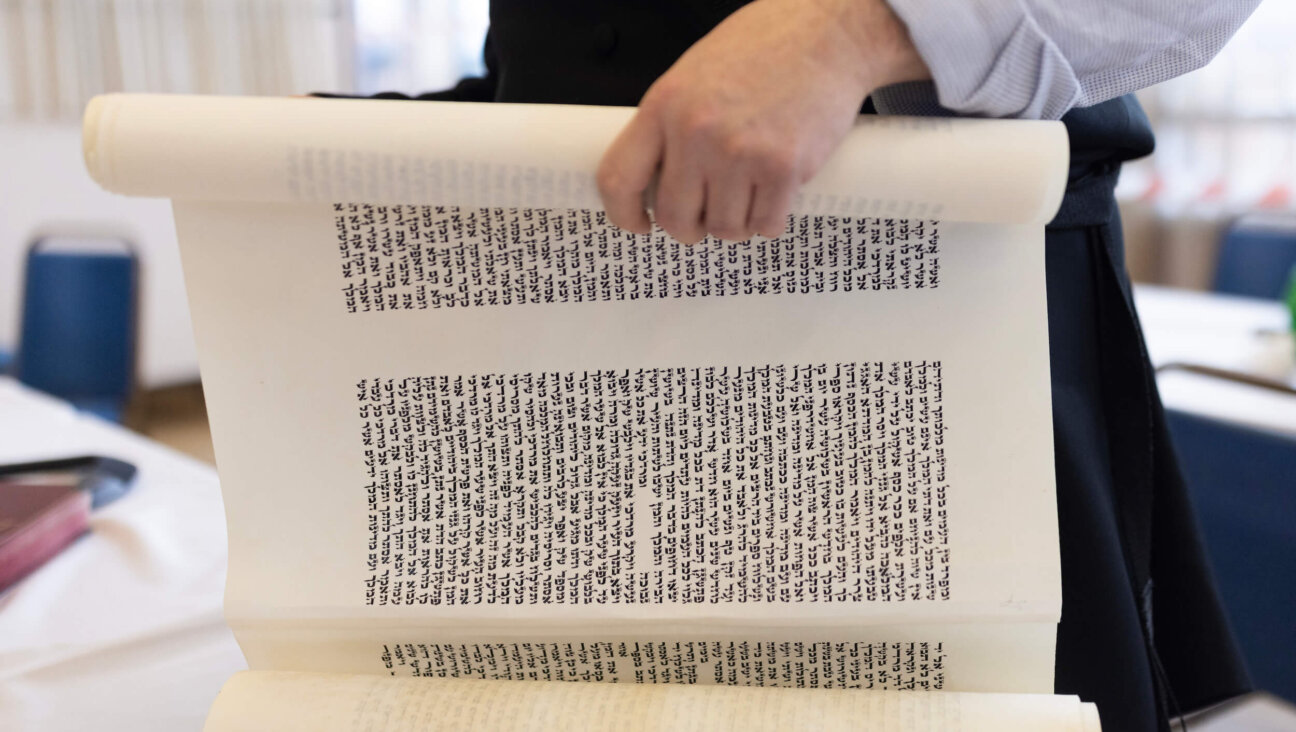

Here are two volumes, then, almost 1,400 pages, of the work of more than 100 writers of prose and poetry born in and born of Jewish Russia. Some fanatics will read this heady, heavy anthology front to back; others, in armchairs, will choose to flip through in pursuit of biographical curiosity or literary whim. No matter the manner of appreciation, though, the parts of “An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature” seem as great as the whole, are greater — they are, and it is, a wonder.

From Leyba Nevakhovich’s 1803 “The Lament of the Daughter of Judah” (which declares, “The religion professed by the Jews is harmless to any citizenship”) to the present-day, disappointed Americanism of Vladimir Gandelsman, the uncomfortable Israelism of Dina Rubina and the proudly nativist humor of Odessan Mikhail Zhvanetsky, “Two Centuries of Dual Identity,” as the anthology’s subtitle describes, become, in effect, two centuries of triple identities, and more — two centuries of multiform sentimentalities and socializations, and their abjuration, or idealization, on the Russian-language page.

After 1934, and the First Congress of Soviet Writers, Russia’s official literati had reached a definitive consensus: A Jewish writer, they would argue, was a Jew who wrote in only Yiddish or Hebrew, and only a Jew writing only in Russian could rightly be called a Russian writer — and only a Russian writer. The anthologizing of these two volumes condemns such a denunciation of cultic life, and then proceeds, by example, to halfway support it. Democracy — which respects religion, and has trumped communism with a capitalist embrace of myriad affiliation, birthright and calling — has ultimately ruled, and, surprisingly, such ruling has much in common with the liberties taken by an autocracy, or fascist regime: A Jewish writer is whoever wants to be called a Jewish writer, and, as if in a resurrection of Soviet denunciation, any writer whom a culture wants to call a Jewish writer, too.

Though ideally a writer’s biography should be the least of a writer’s writing, this anthology is most remarkable for the manner in which, volume by volume, these two “genres” or “works” become editorially balanced, unbalanced and counterposed. Before we get to such famous, contemporary contributors as “Mandelstam, Osip,” we have “Mandelstam, Leon,” born in 1819 in Novo-Zagory, Vilna province, in what is today Lithuania. After being the first Jewish student admitted to Moscow University, Leon Mandelstam was appointed by Prince Sergey Uvarov, Russia’s minister of education, to serve in the position of “expert Jew,” replacing Rabbi Max Lilienthal, future patriarch of Reform Judaism, who had just departed for America. Mandelstam’s many books include a great Hebrew-Russian Dictionary, and its counterpart, a Russian-Hebrew Dictionary, in addition to a famous translation of the Torah. His “The People” is included early in the anthology; it is a traditional dialogue or dramatic poem, and it is apologetic and, to us today, almost untranslatably strange:

“Our people in essence is much like a poem,

There are errors in form and the whole is perplexing;

Its end comes before it begins incorrectly;

Its parts are untidy, the sense does not hold!…”

While this earlier Mandelstam is defeatist, willing to surrender himself and the poem that is his people to a Russian editor, or Christianizing calmative, the latter Mandelstam — Osip, 1891-1938, one of the greatest Europeanized poets of the 20th century — actively courted such “errors in form,” and perplexity. Indeed, because of its very political and aesthetic “untidiness,” Osip Mandelstam’s poetry translates to our own comparatively unblemished milieu as astoundingly pure. In 1933, this most conflicted, contradictory of poets wrote what was essentially a versified suicide note: a poem denouncing Stalin. Mandelstam was arrested and sentenced to five years in a labor camp. He died in the winter of 1938 at a transit camp near Vladivostok. Though Mandelstam was a poet, and though everything he wrote was, in the appreciative sense, poetic, this anthology also collects an excerpt of his prose: “Judaic Chaos,” from “The Noise of Time,” his memoir. In it, Mandelstam memorializes the communicative mode of his birthright: “Father had no language at all; it was hotchpotch, tongue twisting, and languagelessness. The Russian of a Polish Jew? No. The speech of a German Jew? Not that either. Perhaps a particular Kurland accent? I’ve never heard one like his. A totally detached, invented language, a weave of words, the embellished and tangled talk of an autodidact, where ordinary words interlace with the obsolete, philosophical terms of Herder, Leibnitz and Spinoza, the wondrous syntax of a Talmudic scholar, artificial, often incomplete locutions — anything but a language, be it Russian or German.”

Such was and is the bind, or unboundedness, of dual or opposing identity — in modern America and Israel as much as in historical Russia. All Jews, it can be said, are simultaneously Osips and Leons: both assimilationists and individuals, and yet at all times, still Jews. Though “between Mandelstam and Mandelstam there arose no one like Mandelstam,” there were many others, if lesser. This anthology has saved them for us from oblivion.

Falling into this middle firmament, or limbo, between the universally important Osip and the community-critical Leon, are those writers whose works, while perhaps not of the greatest quality, or impact, serve a purpose greater still: They constellate a culture. As Russia does not know from the small, the minor or modest, this anthology offers an enormous abundance, a laden Sabbath table of letters: from the comparatively well-known, such as Vladimir Jabotinsky, Viktor Shklovsky, Boris Pasternak and Vassily Grossman (in chronological order), to the crucial lesser-known, such as Yan Satunovsky, Genrikh Sapgir and Anna Gorenko. Important to remember this: Here in this anthology is the work of the writer, not of the party hack, overwhelmingly the art of the censored more than that of the collaborative, or loyal.

Included also are two stories by Isaac Babel, and two poems about the massacre of Babi Yar, in which the Nazis killed more than 30,000 Ukrainian Jews in the span of two days. The inclusion of these almost opposing poems by Ilya Ehrenburg and Lev Ozerov is a mark of Shrayer’s thoroughness as an editor, and their inevitable juxtaposition in the mind of the reader is a reminder that the responses of art — the responses of humanity — to catastrophe can differ and yet still be affecting, and true.

“Babi Yar” by Ilya Ehrenburg (1891-1967) bemoans the limitation of memory, of empathetic or even documentary hindsight, refusing the twinned consolations of speech and of thought:

“What use are words, pens, paper, banners,

When on my heart this stone descends,

When, like a convict hauling cannon,

I lug the memory of friends?”

Whereas in an oblique act of contradistinction, the poem by Lev Ozerov (1914-1996) demands such speech and thought, such testimony, and demands them from none other than Nature Herself:

“Pleading, here at this place I stand.

If my mind can endure violence,

I will hear what you have to say, land —

Break your silence.”

These two poems are an anthology in iconic miniature of a particular Jewish-Russian aesthetic: Ehrenburg’s, in its exaltation of the human, denies art, whereas Ozerov’s, in its exaltation of nature, denies God. Both denials are, almost, early communist impulses; both are, nearly, early Christian impulses. Together, though, they might serve to define Russian Judaism, or “Jewish Russianism,” in both in its humanistic spirit and its utopian attempt to forge a new order here on earth, whether politically, religiously or communally — the attempt of a culture that is responsible for itself, and that believes change and progress to be not only possible but also necessary.

To be sure, despite their successes (two of the four Russians who have received the Nobel Prize for literature have been Jews: Boris Pasternak, whom the Soviet authorities compelled to decline the prize, in 1958, and, in 1987, American émigré Joseph Brodsky), Russian Jews were always oppressed, and it is, perhaps, this very oppression that enabled their culture to cohere at the margin, or in the underground, without a common cultic language such as Yiddish or Hebrew. In his introduction, Shrayer offers a cursory account of this trauma, giving us the following passage, which is doubly revealing when extrapolated into metaphor, and removed from historical context: “The double-bind of anti-Jewish attitudes and policies during the tsarist era presented a contradiction: on the one hand, the Russians expected the Jews to assimilate if not convert to Christianity; on the other, fearful of a growing Jewish presence, the Russians prevented the Jews from integrating into Russian life by instituting restriction and not discouraging popular antisemitic sentiments.”

Such a double bind might obtain, as well, in Shrayer’s own editorial choice. It seems that to be included in the Jewish-Russian canon, a writer should write well enough for the Russians — to a universal and not just a community standard — but “Jewishly” still. And yet this Jewishness — whether it’s a Jewishness of subject or of style, with the interpolation of shtetl or Torah imagery, or else of Yiddish or Hebrew words — must not, at the same time, alienate or frustrate that Russian, or worldly, readership. This contradictory caveat is reified in Shrayer’s choice of the stories of Isaac Babel, the greatest prose writer of Russian Jewry. Shrayer chooses to include not Babel’s best stories, but those that are most indicative of a Jewish Babel: “The Rebbe’s Son” and “Awakening.” It is telling to note, however, that Babel is at his best, his least sentimental and most savage, in stories with a theme or pretext that is not Jewish but, oppositely, Christian — for example, the great “Pan Apolek,” “Sandy the Christ, or “The End of Saint Hypatius.”

Such editorial conversion becomes more evident as we approach our own times. As Shrayer notes, a century after philosopher Vladimir Solovyov asked, “Why was Christ a Jew, and why is the stepping stone of the universal church taken from the House of Israel?” Russia welcomed the appearance of Father Aleksandr Men (1935-1990), a Jewish-born Russian Orthodox priest who preached apostasy, or conversion, touting Jewish-born Christians as those who were, or would be, “doubly chosen,” first as Jews and then, redoubled, as those who come to Christ. The number of Jews who converted before the fall of communism, and during the tsars, was enormous, was perhaps understandably enormous, and included even the visionary, and intellectually honest, likes of Osip Mandelstam, who in 1911 became, of all things, a Methodist. But after the fall of communism, apostasy grew greatly — strange for a climate of new, if only political, permissiveness. Shrayer, then, in his weakest moment, attempts to define by de-ratiocination, which is by racination — defining Jewishness by bloodline, by birth claim, the maternal affiliation touted by the Talmud. This tenuousness, though, is wonderfully answered, as if in catechism, by Russian Jewish writers in voluntary exile — by those in America, and, especially, by those in Israel.

In Israel, many Russian Jews seem to have found not religion or racial identity but a new, or substitute, nationalism — recombinant of Zionism and the Romantic stirrings of Revolutionary times. Yuri Leving, barely 30 years old as of this anthology’s publication, born Yuri Gershanovich in Perm, presently resides in Kfar Eldad. His poem “Orientation” is the anthology’s last, and, like Leon Mandelstam’s early effort, it disturbs with an olden, almost archaic patriotism, a stunning belief in a host culture’s power to remake, or edit, its minority lives. What initially seems naive here on rereading remains heartfelt, and it becomes evident upon finishing both this poem and, with it, this anthology that Russian nationalism or Russian identity as a modifier or equal to racial or religious Judaism has not been discarded, rather syncretized — taken as metaphor, to be liberally mixed under democracy and sunnier skies.

Leving carelessly canonizes:

“In white parade uniforms

with gilded cords,

milk and honey,

shiny new badges and pins

of their companies and divisions,

sons of Palestinefrom Galilee, from Judea,

from Samaria, from Samarkand,

from hell, from the underground,

from God-knows-where, from Leningrad,

from an old sofa ready to burst with desire

like a fiery flower at the end of summer.”

Joshua Cohen is a literary critic for the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO