Bernstein, Davening in the Vernacular

To Each His Burden: In inverse proportion to size, from Junior on up. Image by COURTESY BAVARIAN STATE OPERA

As difficult as it is for outsiders to understand, especially in retrospect, Leonard Bernstein’s overachieving father, Sam, was so opposed to his son’s fixation with music that neither he nor his wife, Jenny, even showed up for their son’s student debut as soloist in Grieg’s Piano Concerto with the orchestra of Boston Latin School.

Victim of Sehnsucht: Bernstein was unconvinced of his enduring worth. Image by GETTY IMAGES

For Sam, who sacrificed his training as a rabbi to flee to America and avoid conscription into the czar’s military, his firstborn son, Leonard, had to become a rabbi. End of discussion. The only other acceptable choice was to work in the family business. Leonard never recovered from his parents’ missing his debut, and their callous disregard became the substance of his first opera, whose libretto he wrote himself. At first he used his parents’ real names, but later he changed the wife’s name to “Dinah.” The son (“Junior”) does not physically appear in the opera, but is discussed prominently, most pertinently his appearance in the school play, which neither parent attends, although the wife says she’d intended to do so.

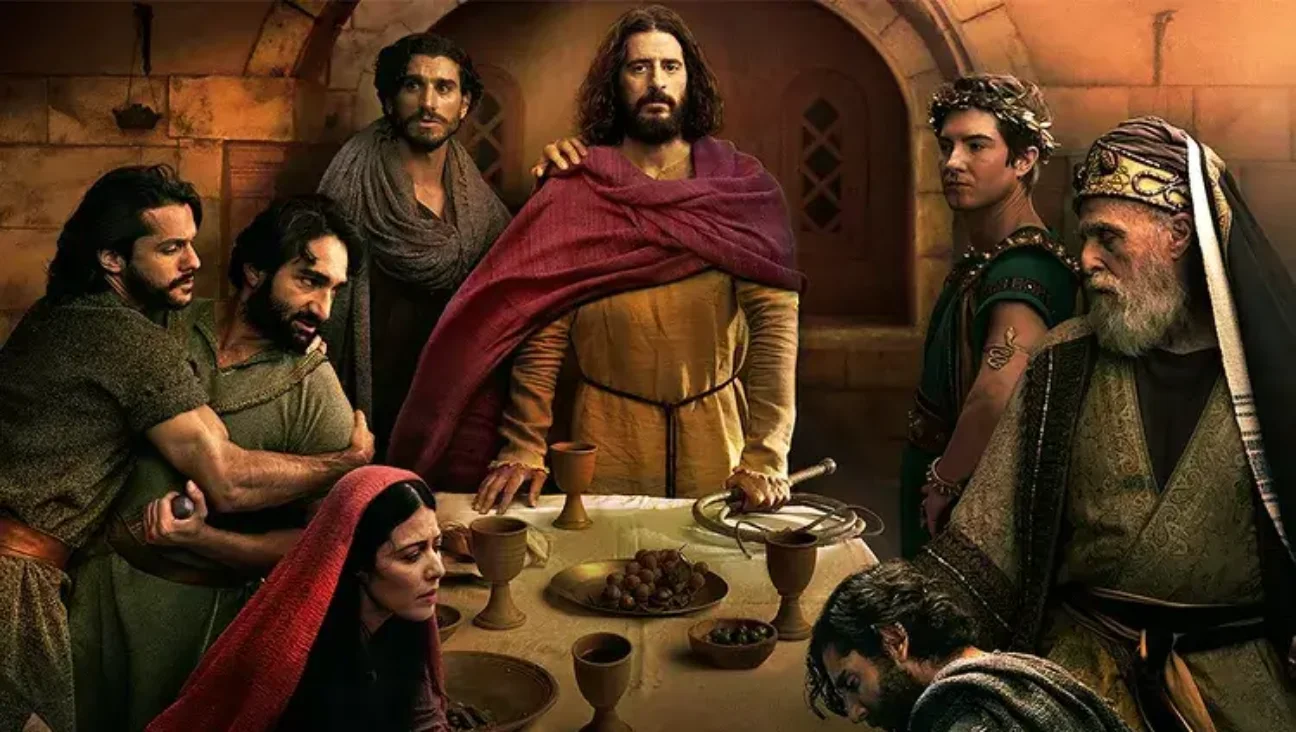

In 11 scenes over a single day, Sam and Dinah show why these two brilliant, driven people ignore their child and have an empty marriage. Celebrating their dysfunction is a “Greek chorus born of a radio commercial,” singing the joys of suburbia and consumerism. The three-singer chorus places the action squarely in the 1950s, the heyday of such “jazz” jinglelike radio commercials. Bernstein deliberately wrote the entire work using popular American vernacular styles rather than the usual “grand” opera tradition. No swans or valkyries here. This is the “bought and paid-for magic” of commercial culture. Dinah even gets to belt out a show-stopper of a rant about Hollywood escapist fare, the imaginary “Trouble in Tahiti” film that gives the opera its title.

Every summer, Munich’s Bavarian State Opera Festival presents a dizzying array of operas. “Family relations is one of the pillars of this year’s opera festival,” explained Kent Nagano, BStO’s music director. “I thought “Trouble in Tahiti” would be the perfect companion to Wagner…It’s almost “Lohengrin Part 2,” he laughed.

To Each His Burden: In inverse proportion to size, from Junior on up. Image by COURTESY BAVARIAN STATE OPERA

It is a bold move to contrast Wagner’s murky mystical doings with Bernstein’s equally dysfunctional, but decidedly more down-to-earth setting. Bernstein has an American middle-class couple where Wagner has a mysterious main character arriving on a magic swan to save his intended Elsa from auto da fe, but depart, leaving behind the supposedly murdered but magically restored “führer of the future.”

Munich has always been music-mad, and the centuries-old BStO maintains three separate opera houses. One of the world’s most important, BStO is the company of Prince Ludwig, whose fairy-tale castles inspired Disneyland, and who bankrolled Wagner while eschewing his antisemitism. Five of Wagner’s most important operas were introduced there. So, pairing Wagner and Bernstein carries more weight here than elsewhere. While “Lohengrin” was presented in the largest of the three houses, the National Theater, where Wagner would have seen it, Bernstein’s “Tahiti” was presented in the smallest, the over-the-top rococo Cuvilliés Theater, the jewel-box opera house where Mozart premiered his “Idomeneo.” Such was the demand, that all three performances of “Tahiti” were completely sold out almost immediately.

Nagano conducted both “Lohengrin” and “Tahiti” with superb musicianship and conviction, utterly at home with both traditions. Both were major new productions. The Bernstein had the prestigious Mahler Chamber Orchestra premiering a new 14-musician reduction of the score in the pit. “Tahiti” is a swift 45 minute work for five singers, requiring little in the way of sets. Unfortunately the director, Schorsch Kamerun, decided to go over the top, filling the stage and crowding out the opera itself: Sam gets to right a fallen giant lizard in an abandoned amusement park; blow-up dolls of the characters walk on and off and deflate; extras appear, wearing crass beach-wear; a flashing sign “Suburbia” appears. Against Bernstein’s wishes, the neglected child appears here throughout the work. Completely silent, he forlornly drags a battered stuffed bunny. The Trio chorus (elegant evening dress in the original) are clowns here. But worst of all, since “Tahiti” is so short, Kamerun adds “Before the Trouble Gets Going” — four cringeworthy German punk songs, reflective of the 1970’s social disengagement, declaimed in front of the curtain. Still, the Bavarian audience was clearly moved by this mismatched couple, particularly at the ambiguous, not-so-happy ending.

“Tahiti” is an exuberant work, a vivid postcard from the beginning of Bernstein’s career, 1952. He had set out to “out-cradle” his friend Marc Blitzstein’s notorious “Cradle Will Rock,” which, with humor and music reminiscent of Brecht and Weill, had musically satirized capitalism. In the remarkable new book “Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician” (University of California Press), author Barry Seldes points out that Bernstein’s own performance of “Cradle” as a student at Harvard remarkably paralleled the notorious succès de scandale of that work’s New York premiere.

“Tahiti” is, however, less about Marxism and more about how happiness, love and “harmony and grace” lie elsewhere than in materialism. Seldes’s book is a fascinating, if uneven, attempt to define the political journey Bernstein made in his life testing that assertion. Seldes has the advantage of having read the FBI files on the composer, which provide some of the more grimly fascinating anecdotes in the book. For example, how President Truman snubbed Chaim Weizmann because his advisers didn’t want him to be seen at the same function as Bernstein. Bernstein was briefly blacklisted, and Seldes’s book quickly explains the seriousness of the situation, but only in passing does it mention Victor Navasky’s important book, “Naming Names” on that truly critical historic morass.

Particularly nasty were Bernstein’s ongoing run-ins with J. Edgar Hoover, who was determined to damage Bernstein. For a time he was even denied a passport, which prevented him from conducting abroad. Bernstein, however, was extremely lucky to have had a close friend in Senator (and later President) John F. Kennedy, whose personal intervention saved him more than once, to the great frustration of Hoover and his cohorts. Then-president Nixon, for example, deliberately stayed away from the opening of the Kennedy Center, for which Bernstein had composed his Mass commemorating Kennedy. Seldes goes into some detail about how Bernstein sought out the prisoner of conscience Daniel Berrigan in his research for that work. Nixon suspected that the whole work was to be an attack on him. But no summary can do justice to the sheer range of Bernstein’s history here.

Bernstein was not totally innocent of playing games himself. In a damning episode, Bernstein — evidently with little guilt — participated in the successful and secret attempt to destroy the career of Dimitri Mitropoulos, the highly regarded conductor of the New York Philharmonic. Mitropoulos was responsible for giving Bernstein the biggest break of his career: the national radio broadcast of a regularly scheduled New York Philharmonic broadcast, which got him the attention of not only the nation, but also the front page of The New York Times.

Mitropoulos had a secret: He was gay. From bitter experience he advised Bernstein (also gay) to get married for professional reasons, which he did. When Serge Koussevitzky, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, founder of Tanglewood and another of Bernstein’s early mentors, was seeking to have Bernstein succeed him, he asked for any information that would damage Mitropoulos’s candidacy. Shamefully, knowing to what end the information would be used, Bernstein gave up Mitropoulos’s secret without hesitation. It did not help Bernstein get the job, but it doomed Mitropoulos’s career.

Much of the book’s most startling information is in the footnotes. Despite Seldes’s best efforts, for eras like the 1930s and 1940s, with so many diverse, fractionalizing political groups, it becomes quite a chore to follow. Seldes seems scrupulous in his attempt at accuracy, although he leaves little doubt as to where his sympathies lie. Bernstein’s explanation for his proliferating associations is that he needed publicity and lent his name to any and all causes. There is truth in this, but also disingenuousness — but such disingenuousness was unfortunately rife during the witch hunts that began under the Truman administration. The FBI files that Hoover accumulated on Bernstein show a degree of recklessness that is at a minimum reprehensible. Included, for example, in one footnote is one of Hoover’s letters, directing his operative to coordinate a letter-writing campaign to discredit Bernstein and to do so anonymously “with additional phraseology such as “A Concerned and Loyal Jew,” or some other similar phraseology.”

Some things, however, Seldes gets quite obviously wrong. Bernstein’s famous performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony — controversially changing the words of what had been the “Ode to Joy” (“An die Freude”) to “Ode to Freedom” (“An die Freiheit”) — was to celebrate the reunification of East and West Germany, not the reunification of Europe. In a book of this size (250 pages, of which 50 are for footnotes, it is not possible to be synoptic; nevertheless, the treatment of individual compositions is somewhat haphazard. Some are psychoanalyzed in detail. Others are barely mentioned. Sometimes the writing on the music is perceptive and crisply described. Other times a major work is barely mentioned in passing, or described as if by another, foggier, writer.

Almost nothing of the process of composing makes it into this book, because that is not its purpose. Ditto performing. At the end, there is frankly foolish philosophizing about Bernstein’s ambitions to be an opera composer. But where Seldes is good, he is very good indeed. My most searing memory of Bernstein comes from backstage at Avery Fisher Hall, just as Bernstein and his ever-present entourage boarded the elevator. They were vainly reassuring him how great his music was. He broke away from them to ask me, a student at the time, and the only one in the elevator not known to him, whether I thought he had composed anything that would last. I was shocked at how deeply, how profoundly, he doubted he had. Nothing I or anyone else could have said could have rescued him from his personal, private hell.

At the end of his career, Bernstein did finish a full-length opera, “A Quiet Place,” which revisits (and includes) “Trouble in Tahiti.” The high spirits of youth are gone here. In the work, set 30 years later, Dinah has died in a car accident, and the family gathers for the funeral. Junior has grown up gay and psychotic. He has a sister, Dede, who is married to his former lover, François. All are estranged from Sam, but reconciliation is attempted. Unlike “Tahiti,” “A Quiet Place” has not found success. When asked why the BStO had not produced the later, fuller work, Nagano mused:

You know, “A Quiet Place” stays on my piano. It has a personal meaning. I was working closely with Leonard Bernstein when he was working on the production in Vienna with “Trouble in Tahiti” as a flashback. He was one of our greatest geniuses. What the man said and did was so visionary. Like so many visionary things, we need time to look back to be able to fully understand it.

And then he used an untranslatable German word to sum up what for him expressed the ache at the heart of Bernstein’s work: Sehnsucht, the almost mystical, intense longing for something indefinable. Sehnsucht is central to Wagner’s operas and was also at the core of Bernstein’s being. “I’m not a musician; I’m really a rabbi,” Bernstein himself explained, in a footnote. For him, composing and performing were not simple musical activities, as they were for others. They were the only path available to him to try to live up to the demanding vision his father had for him of becoming a rabbi. His whole life and career, in retrospect, were for him like davening on behalf of Sam.

Raphael Mostel is a composer based in New York City. He teaches at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation of Columbia University.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion Trump’s Israel tariffs are a BDS dream come true — can Netanyahu make him rethink them?

- 2

Fast Forward Cory Booker’s rabbi has notes on Booker’s 25-hour speech

- 3

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

- 4

News Rabbis revolt over LGBTQ+ club, exposing fight over queer acceptance at Yeshiva University

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Muslim prayer room at NYU vandalized with name of Jewish fraternity

-

News Jewish cultural institutions reeling as Trump defunds arts and humanities

-

Fast Forward A publisher is reissuing a 1931 novel to bolster Jewish representation in Hollywood

-

Fast Forward It’s official: Southeast Florida’s Jewish population is growing — and getting younger

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.