Renovation of Storied Toronto Synagogue Opens Cracks in Congregation

Toronto – What began as a grandiose plan for renewing a jewel of the synagogue world has ended up causing a communal identity crisis at one of Canada’s most storied Jewish congregations.

The crisis came to a head last week when almost 2,500 members of Toronto’s Holy Blossom Temple — a 150-year old Reform movement synagogue — participated in a contentious vote on plans to change the layout of their Toronto landmark.

The current Holy Blossom structure, which has hosted some of the most famous Reform theologians, was designed in Romanesque Revival style in the 1930s when the Reform movement had a more ambivalent relationship to Zionism and when the sanctuary was made to face west, away from Jerusalem.

Three years ago the synagogue leadership embarked on a renewal plan — created by the same architects who did Toronto’s opera house — in which the sanctuary would be turned around 180 degrees to face Israel. The redesign would also relocate the bimah, an elevated platform for prayer, to the center of the sanctuary, a location historically associated with Orthodox Judaism.

The push for changes at Holy Blossom is in keeping with the general trend in the Reform movement toward greater ritual observance. Holy Blossom’s leadership has tried to play down the religious significance of the changes, but for one of the continent’s most iconic Reform synagogues to contemplate such changes carries symbolism that extends far beyond Toronto.

“To change in these synagogues is a bigger deal,” said David Kaufman, a professor at the Los Angeles campus of the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College. “The fact that Holy Blossom Temple is thinking of throwing that out the window is incredible, now that I think about it. It marks some water shed, unquestionably.”

This has not been lost on Holy Blossom’s members. The planned changes have since faced stiff opposition from synagogue members who have argued for the value of Holy Blossom’s own traditions and for the architectural value of the current structure. The “Sanctuary Legacy Group,” which has its own Web site, eventually ended up rallying 42% of the vote against the reorientation.

“I think I can say with a high degree of certainty that the temple community is deeply damaged,” said longtime synagogue member Merle Kriss, one of the leaders of the opposition. “Of the group who opposed the reversal of the sanctuary, some will leave, some will maybe say it’s not so bad, but none will feel as they did before this happened.”

While the plans for reorientation now appear to be going ahead, Kriss says that her group has retained legal counsel and is considering its options. Along with the group’s concerns about tradition, Kriss and other members say they were not informed about the plans to reorient the sanctuary until last fall.

Benjamin Applebaum, executive director of Holy Blossom, said that “the board is obligated to implement the will of the congregation. We’re moving forward now to the detail-planning stage.”

Holy Blossom’s rabbi, John Moskowitz, says that he was taken aback by the controversy and that he had not considered the potential significance of the changes.

“It’s not something I thought about,” Moskowitz told the Forward. “It’s a bit embarrassing, but I was not thinking about it politically or religiously, only about the architectural and community integration.”

In recent months, though, Moskowitz lobbied hard for the new additions by focusing on the fact that the new sanctuary would be facing east. In an April synagogue bulletin, Moskowitz quoted another synagogue member: “Now that we have the opportunity to reorient the Sanctuary, even putting aside that it makes sense architecturally to do so — to turn our back on Jerusalem in the current context would be too telling and unforgivable.”

Kriss and other members of the opposition have said that Moskowitz’s references to Zionism are an exploitation of a hot-button issue.

“Using Zionist appeal to press the issue has caused a lot of ill feeling,” Kriss said. “You can be for Israel and maintain the sanctuary as it is.”

Holy Blossom was established 150 years ago, originally as an Orthodox synagogue. Its unusual name comes from the talmudic term for young men preparing for the priesthood. Thirty years after the founding, it joined the Reform movement. The 1885 Pittsburgh Platform ordained that Jews should be considered a religious community and not as a nation.

In the 1920s, Reform rabbis began warming to the idea of Zionism, but not Maurice Eisendrath, the rabbi at Holy Blossom. In an essay on Holy Blossom, published in 1998 in Toronto Life magazine, Canadian journalist Robert Fulford wrote that Eisendrath “developed the idea of Holy Blossom as a Jewish equivalent of a cathedral church, a place of ideas and leadership for Jews and non-Jews.”

Thus came the current structure on Bathurst Street, with its west-facing sanctuary and its famous blue apse, symbolizing the “dome of heaven.”

Holy Blossom has long been considered a northern architectural counterpart to New York City’s grand Temple Emanu-El, which recently underwent its own $25 million renovation (the sanctuary there has long faced east).

In Toronto, Holy Blossom began preparing in 2000 for what is now estimated to be a $35 million facelift. It was then that Moskowitz put out his call for a “paradigm shift in the culture of Holy Blossom Temple.”

There was talk early on of architect Frank Gehry doing the work, though in 2001 he reportedly told The Globe and Mail, “How do you put up a new building without trivializing what’s already there?”

The winner of the 2004 design competition was the Toronto firm of Diamond + Schmitt Architects Inc., which also did the Jewish Community Center in Manhattan, located on the Upper West Side, as well as the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts in Toronto. The head of the firm, Jack Diamond, told the Forward that the Holy Blossom’s buildings and facilities “were long past their sell-by date.”

Diamond says that his idea for adding a new atrium to the structure naturally turned the synagogue around so that congregants would not enter the sanctuary from the main street outside.

“As it happens, it works out naturally that it went to the east,” Diamond told the Forward. “It was a wonderful coincidence. Why do it? Why not?”

Within Jewish tradition there is some ambiguity about the orientation of a sanctuary. Kaufman said that “historically, there was a lot of laxity. If you had a plot in one direction, you simply ignored the issue, and immigrants were not careful with the compass.”

Now, though, Kaufman says that a synagogue “would want to face east if they they could.”

Perhaps the bigger religious change was the addition of the central freestanding bimah, which will be installed in the middle of the seats, as is the case in many traditional Orthodox synagogues. The feature will mark a firm break with the Reform custom, widely adopted by other movements, of having the altar in front of the congregation.

Kaufman said that the “bimah is something different that architects can give congregations. Selling it to them as greater Jewish authenticity, which is all the rage these days, the architect can add value to design.”

The moves being considered at Holy Blossom are also going on at other synagogues. A synagogue in East Hampton, N.Y., recently added a bimah-like structure, while one in Los Angeles is adding a new east-facing sanctuary complete with a traditional bimah set on the side to complement the old one that faces south.

Members of the Sanctuary Legacy Group in Toronto say that the new plan gives too little acknowledgement of the synagogue’s own traditions.

“There is also a special irony in the case being made for reorientation,” Kriss wrote on the group’s Web site. “Proclaimed as a way to enhance community, turning the sanctuary around would entail a painful sense of loss for many members who see its majestic architecture as part of our local and national Jewish heritage.”

In 2005, a survey of the congregation was taken and the Strategic Planning Committee wrote that “while many people were prepared to discuss the possibility of a change to the sanctuary, the overwhelming consensus was to leave the basic structure of the sanctuary alone.”

Michael Marrus, a University of Toronto professor who has been a leader in the opposition, wryly referred to that report.

“Leave the basic structure of the sanctuary alone,” he said. “Wise advice. Why was it not followed?”

Now, with the plan appearing to go ahead, Marrus says: “The congregation is deeply divided. One side will win, and who heals the wounds?”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Deborah Lipstadt says Trump’s campus antisemitism crackdown has ‘gone way too far’

-

Fast Forward 5 Jewish senators accuse Trump of using antisemitism as ‘guise’ to attack universities

-

Fast Forward Jewish Democratic Rep. Jan Schakowsky reportedly to retire after 26 years in office

-

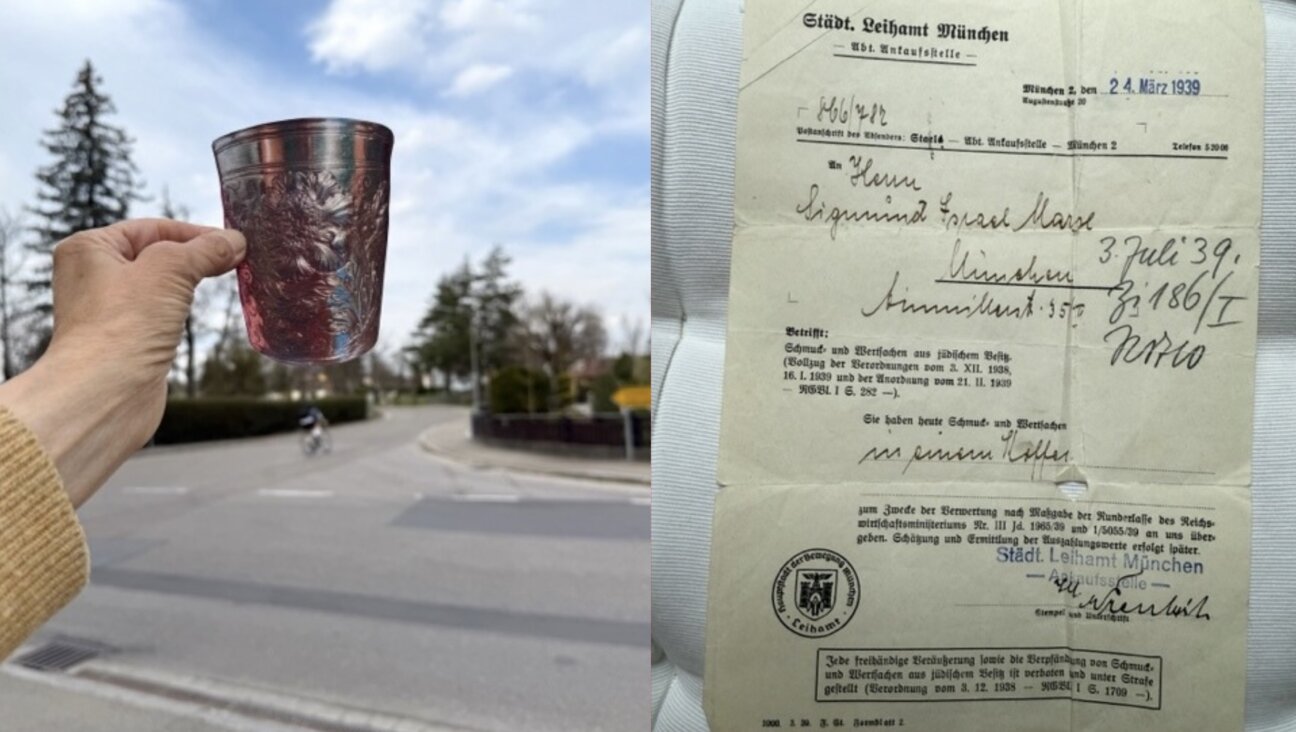

Culture In Germany, a Jewish family is reunited with a treasured family object — but also a sense of exile

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.