Master of Reading

Gilad J. Gevaryahu writes to ask my opinion of a grammatical error in Hebrew that he noticed has been spreading in Orthodox religious circles in recent years. It goes back, he points out, to a mistake that was common in Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe, one that no longer seems mistaken to most people, because it has long been a traditional usage — namely, calling the Torah reader in the synagogue a ba’al-korei.

What’s wrong with ba’al-korei? Well, as Gevaryahu writes, according to the rules of Hebrew grammar, these two words do not mean, as they are supposed to, “a reader [of the Torah].” Here’s why:

The word ba’al in Hebrew (which etymologically goes back to the name of the ancient Semitic god Ba’al) can be either an ordinary noun, in which case it means (to the dismay of some feminists) “owner,” “master” or “husband,” or else a grammatical particle prefixed to a noun, in which case it functions like the English suffix “-er.” Melakhah, for example, is the Hebrew word for “work” or “craft,” and a ba’al-melakhah is a worker or craftsman; din means law, and a ba’al-din is a litigant, etc.

But korei is not a noun. It is a verb, the present-tense, singular, masculine form of lik’ro, to read, as in “He is reading,” hu korei. Just as one can speak in English of a “read-er” but not of a “reading-er,” so ba’al korei in Hebrew is illogical. If you want to refer grammatically to a Torah reader using the ba’al construction, you have to take the noun keri’ah, “reading,” and say ba’al-keri’ah,— that is, “a master of reading.”

But though ba’al-korei rather than ba’al-keri’ah may be bad enough, this erroneous form is now metastasizing, Gevaryahu complains, to other expressions in the Orthodox world, so that he has been hearing a shofar blower referred to as a ba’al-toke’a, a “blowing-er”; the author of a halachic book as a ba’al-meh.abber, a “writing-er,” and so on. The correct expression for a shofar blower is, of course, a ba’al-teki’ah, for the author of a book, a ba’al-h.ibbur, etc.

I must say that I have never encountered ba’al-toke’a, ba’al-meh.abber or any similar expressions other than ba’al-korei — but then again, I don’t move in the Orthodox circles in which Gevaryahu does. When it comes to why some Jews started saying ba’al korei rather than ba’al keri’ah in the first place, however, I have a theory. It may or may not be right, but you know me well enough by now to know that the fear of being wrong has never kept me from theorizing.

The noun keri’ah in Hebrew actually has two different meanings and two different spellings. Spelled with the letter Alef as dixw, it means, as we have said, “reading,” from the verb for “to read,” lik’ro,exwl. Spelled with the letter Ayin as drixw, it means “tearing,” from the verb for “to tear,” lik’ro’a, rexwl. Furthermore, each of these meanings of keri’ah has a specifically ritualistic sense alongside its more general one. Keri’ah with an Alef refers to the reading of the Torah in the synagogue. Keri’ah with an Ayin refers to the act of tearing one’s garment at the onset of mourning for a close relative — a custom with which anyone who has been to a traditional Jewish funeral is familiar. And therefore, a ba’al-keri’ah can also be one of two things: either a “read-er” of the Torah, or a “tear-er” of his or her garments — that is, a mourner who is obliged to carry out the act of keri’ah.

In Jewish societies in the Middle East, which pronounced the Alef and the Ayin differently, as was done in ancient Hebrew and is still done in Arabic, the distinction between the ba’al-keri’ah who was a Torah reader and the ba’al-keri’ah who was a mourner was clear. In Ashkenazic Europe, however, where the Ayin lost its pharyngeal quality and came to be pronounced just like an Alef, the distinction was lost. Now, ba’al keri’ah a Torah reader and ba’al keri’ah a mourner sounded exactly the same. How was one to distinguish between them?

The solution to this problem was, I propose, to call a Torah reader, quite ungrammatically, a ba’al-korei. This kept him from being confused with a mourner not only because one was now a ba’al-korei and one was a ba’al-keri’ah, but also because even if you performed the same ungrammatical operation on the mourner, you would call him a ba’al-kore’a rather than a ba’al-korei and still hear the difference even in Ashkenazic lands.

That’s my theory, anyway. How upset one should be with new usages like ba’al-toke’a or ba’al-meh.abber is another question. Hebrew purists may want to tear out their hair. The linguistically more permissive, on the other hand, may shrug and say: “So the grammatical rule has changed, so what? If ba’al korei didn’t bother anyone in the past, why should ba’al-toke’a or ba’al-meh.abber bother us now?” As for me, I’ll stay out of it. Let the Orthodox work it out among themselves.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

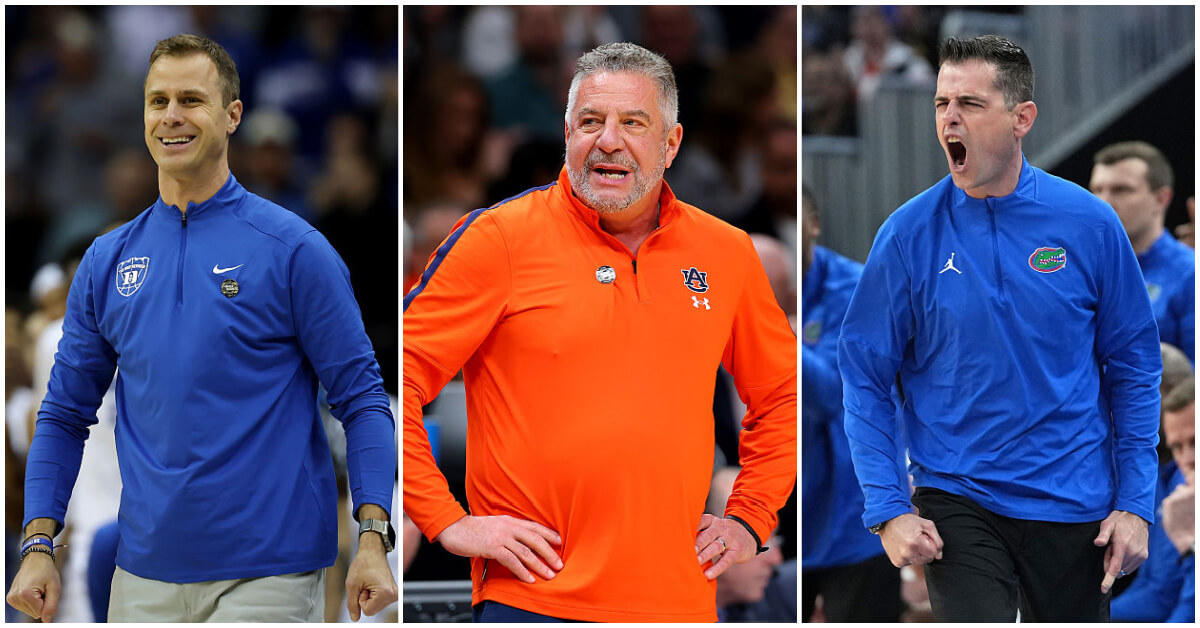

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

News Who would protect New York Jews better? Cuomo and Lander trade attacks on the campaign trail

-

News Rabbis revolt over LGBTQ+ club, exposing fight over queer acceptance at Yeshiva University

-

Opinion In Qatargate fiasco, Netanyahu’s ‘witch hunt’ narrative takes cues from Trump

-

Yiddish די הגדה ווי אַ לעבעדיקער דענקמאָל פֿון אַשכּנזישער פּאָעזיעThe Haggadah as a living monument to Ashkenazi poetry

אַמאָל זענען די פּייטנים, מיסטישע דיכטער־וויזיאָנערן, געווען אויבן־אָן בײַ די פֿראַנצויזישע און דײַטשישע ייִדן.

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.