Jerusalem Plans a Hero’s Burial for Long-Deceased Grandson of Herzl

In one of the stranger commemorations planned for Israel’s upcoming 60th birthday, a man’s body will be disinterred in Washington, D.C., and moved halfway around the world to Jerusalem.

The body being moved is that of Stephen Norman, the only grandson of the modern Zionist movement’s founder, Theodor Herzl, and the only descendant of Herzl to take much interest in Zionism.

The move comes after a lengthy campaign by a small group of Washington-area Jews, who wanted to see Norman buried on Mount Herzl, the cemetery for Israel’s national heroes that was named for Norman’s grandfather. The Israeli establishment has resisted these efforts — in line with the country’s larger estrangement with Herzl’s family — but now, for the 60th anniversary, the impossible is set to happen.

“He was the only Zionist among Herzl’s descendants,” said Jerry Klinger, president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. “Bringing him to Israel is significant; it shows that we are one people.”

The reburial is set to take place in November, and while it will make for a feel-good celebration, it will also serve as a reconciliation of sorts between the Zionist establishment and the tragic, long-ignored saga of Herzl’s family.

Herzl himself died in 1904, at the age of 44, leaving behind three children. Pauline, the oldest daughter, died in a French sanatorium at 40, and Hans, the middle child, committed suicide a few days later.

Trude was the only one of Herzl’s children to marry. She and her husband, Richard Neumann, had one child, Stephan, who was sent off to England as the Nazis took over Austria. During the war, the young man (who would Anglicize his name) joined the royal British artillery regiment and was sent overseas.

His travels gave him a chance not only to get acquainted with his grandfather’s writings but also to visit Palestine. The short tour made a deep impression on Norman. In an essay he wrote after the visit, he described with amazement the “normal” younger Jewish generation he found in the land of Israel.

“Whoever they were,” Norman wrote of the children of Tel Aviv, “they had the look of freedom. I thought of the dark, sallow, unhappy Jewish children of Europe. I had seen pictures of their faces; their youthful frames had borne the features of old men and women, and now I saw these little ones who look like children again.”

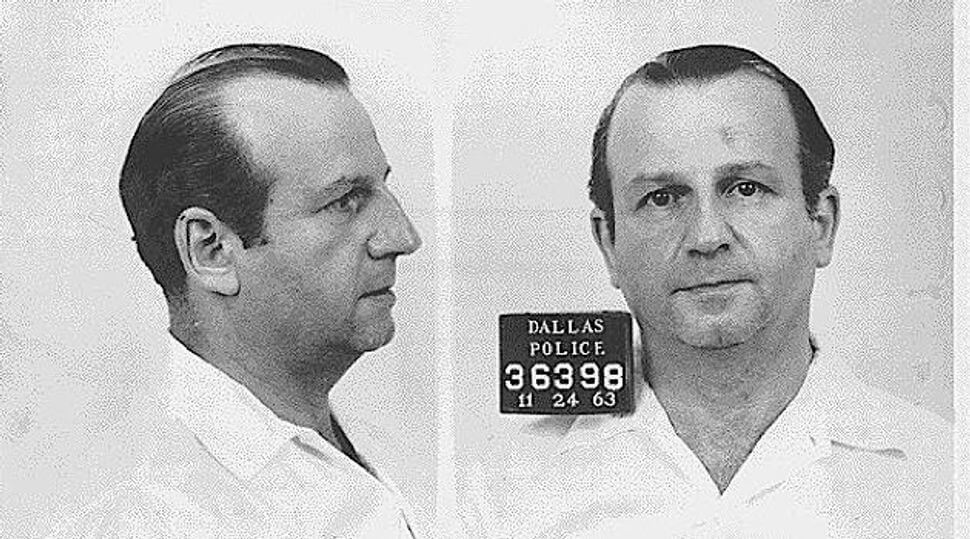

But tragedy was never far away. After the war, Norman was posted in Washington, where he learned that his parents had both been killed in Theresienstadt. Norman walked over the Massachusetts Avenue bridge near the British Embassy and took his own life. The Jewish Agency gave him a quiet burial at the old Adas Israel cemetery in Southeast Washington, where he was largely forgotten for decades.

Klinger, the Washington activist, said that one of the reasons for Norman’s hopelessness was his belief that his grandfather’s dream of a Jewish state would never come true. He died 18 months before the declaration of an independent Israel.

The historic preservation society got involved with the matter five years ago, after Klinger read about Stephen Norman and learned that he was buried in Washington. In 2003 the society began campaigning for his reburial in Israel. Winning over Zionist organizations to the idea, however, proved difficult. Klinger lobbied American Zionist organizations and even schools and summer camps named after Herzl. “Nobody gave a damn,” he said.

In an act of desperation a little over a year ago, Klinger went to Norman’s gravesite in Washington and took a handful of soil. He packed it in his bag, took it to Israel and sprinkled it on Herzl’s grave. Klinger brought back to America some dirt from Herzl’s grave and placed it on Norman’s grave.

The breakthrough came after that, when the World Zionist Agency and the State of Israel arranged for the bodies of Herzl’s children — Pauline and Hans — to be moved to Israel, as Herzl himself requested in his will. The government had taken this action in response to calls from Israeli scholars who raised the issue in 2004, the centenary of Herzl’s death.

In America, the work of Klinger and his fellow activists shed light on the other forgotten descendant — and with Israel’s 60th anniversary, suddenly their effort attracted some notice.

A spokesman for the World Zionist Organization, Michael Jankelowitz, said that the organization, which owns the Mount Herzl cemetery, began to take action on the issue following the rise in interest in Israel and overseas in Herzl’s family.

“For many years, no one showed any interest in Herzl’s children, not to mention his grandson,” Jankelowitz said.

There was one final hurdle to be jumped. Since Norman committed suicide, he is not permitted under rabbinic law to be buried inside the cemetery. Lengthy research into the Herzl’s family history by Klinger and historians in Israel, however, produced a document stating that Herzl and his family suffered from a genetic mental disease known as familial depressive illness.

Norman’s body is to be exhumed in early November. After memorial ceremonies are held in Washington and New York, it will be flown to Israel for final burial at the family plot on Mount Herzl.

For Klinger, the end of the odyssey is also an opportunity to use the Herzl story for getting American Jews closer to the idea of Zionism. He is now trying to promote a program of learning Herzl’s legacy in a similar manner to that being taught in Israel since the Herzl Law was enacted three years ago.

“I suggest that once a year we have an international Herzl Day in which every school, synagogue and organization talks about his legacy,” Klinger said. “Maybe the return of Norman’s body to Israel can be the bridge we need in order to get this started.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO