Free Services Are the Ticket To Continuity

A s the High Holy Day season draws to a close, let us face the reality that many Jews, in particular young ones, are going to show up at a synagogue only on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur — and some will not show up at all.

It is ironic that we American Jews, who are so worried about our shrinking numbers, close our synagogue doors to those who actively seek us out at this intensely Jewish time of year, just because they have not purchased tickets. What sense does it make to create programs all year long to reach out to disaffected Jews, but then bar them from entering at High Holy Day time? It is precisely at this time that we should open our doors as wide as possible.

We behave in this self-contradictory manner because we cannot free ourselves from thinking the way we did generations ago. Back then, when the Jewish community was more cohesive, any Jew who would not buy a costly ticket for High Holy Day services was considered a freeloader and kept out.

The searching young Jews who are showing up today, by contrast, generally still feel connected to things Jewish.

If we deny them admission to High Holy Day services, they may drift away, never to return. But if we capitalize on their desire to spend time with us, we might just be able to hold on to them.

We need to create separate services for them that are geared toward their needs: where along with the cantor’s chanting, the rabbi explains what is going on and imparts nuggets of Jewish wisdom; where the congregation is taught the High Holy Day nusach, or recurring melody, and is encouraged to sing it together with the cantor; where the prayer book contains transliteration of all key prayers so that people who cannot read Hebrew can still join in; where people are asked to actively discuss the Torah reading in small groups in between aliyot; where a light lunch follows the Rosh Hashanah service and a break-fast follows Ne’ilah so that people can shmooze with each other.

But we should not stop there. We need a service where there is no solicitation of funds; a free service so that people who would not spend money on a ticket will choose to attend; a walk-in service so that people can make up their minds at the last minute that that is how they want to spend time on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; a full service, and not an embellished yizkor service.

Back in 2004, with these ideas percolating in my mind, I experimented with such a service. I encountered reasonable success, and have repeated the experiment each year since.

A long time ago

we lost 10 tribes.

It is now time

to find them.

This year, the project, called Ohel Ayalah, attracted 300 people to a Rosh Hashanah service, 550 to two back-to-back Kol Nidrei services, and 150 to Ne’ilah. About 75% of those who attended were in their 20s and 30s. Other community services, with somewhat different philosophies, have also attracted large numbers.

What these figures show is that if you offer young people a service aimed at them — one that does not create in them the feeling that they are not Jewish enough but instead accepts them for who they are, one that has as its sole goal keeping them connected Jewishly — then they will flock to it.

Are such free services undermining synagogues? Not at all. By warmly welcoming these young Jews in their interim years — the time between graduating college and settling down when many do not choose to join a synagogue — such services will augment membership later on.

We need to spend our communal funds on establishing such services in a wide variety of places, beginning with the metropolitan areas where many young Jews live. We need to hire community rabbis, ones unattached to any particular synagogue, who would work on such projects. And since young Jews get their information electronically, we need to create Web sites advertising these services.

We cannot afford to live with the attitudes of the past. Every Jew is precious; every Jew is worthy of our attention. A long time ago we lost 10 tribes. It is now time to find them.

Rabbi Judith Hauptman, a professor of Talmud and rabbinic culture at the Jewish Theological Seminary, is the founder of Ohel Ayalah.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

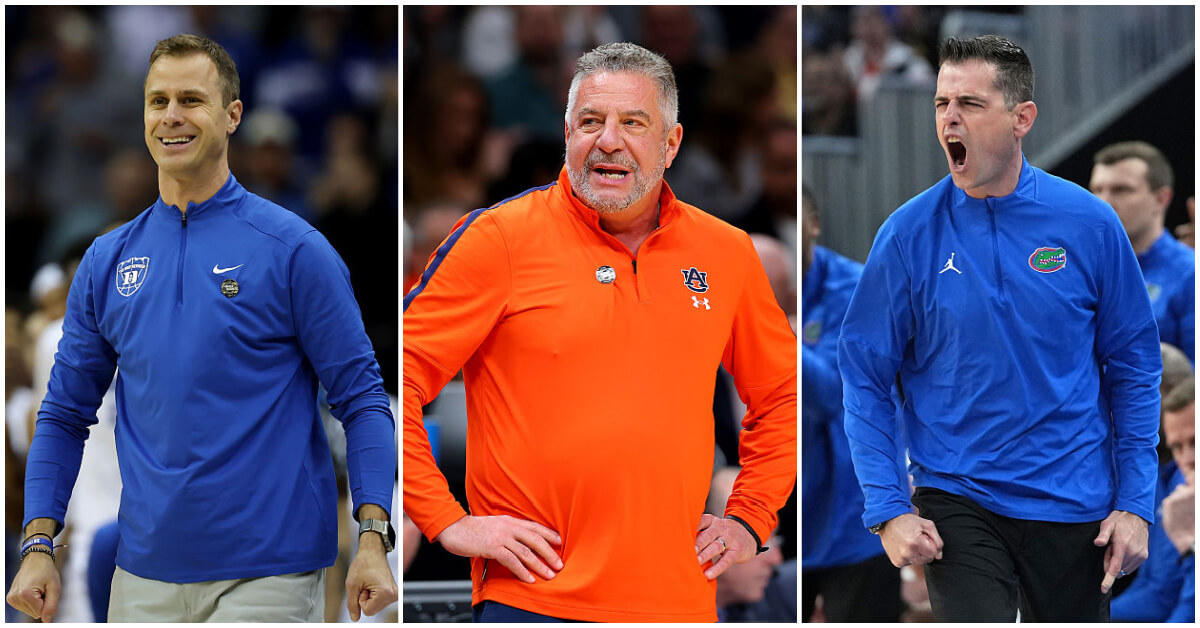

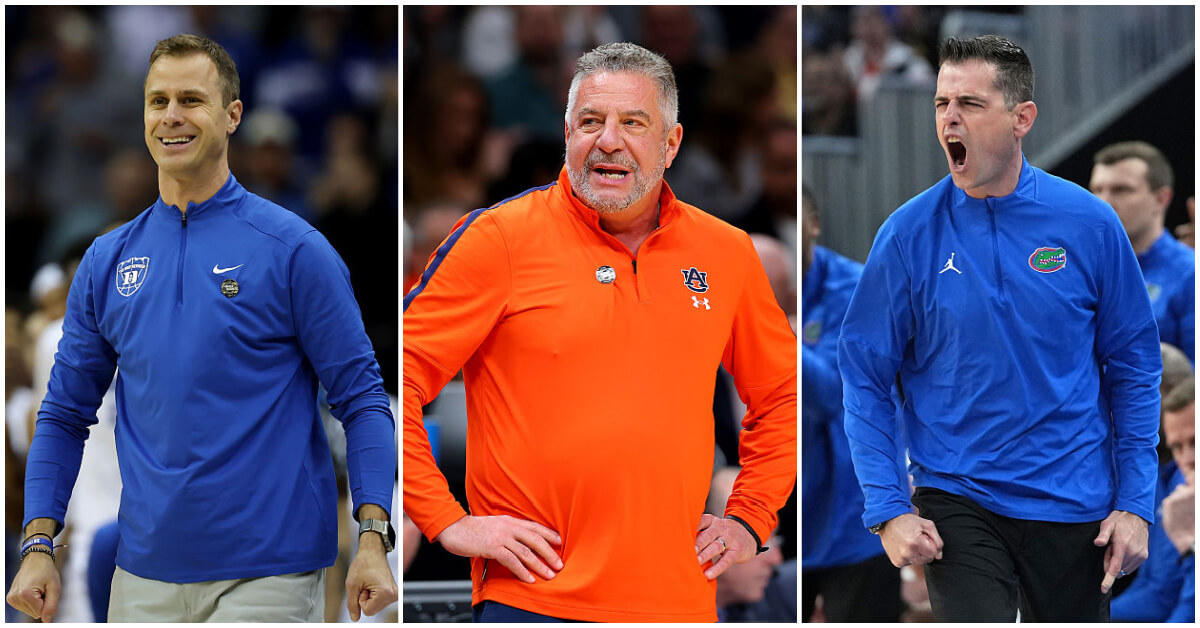

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.