Setting Celan To Music

The distinguished literary critic George Steiner once described the Romanian Jewish poet Paul Celan as “almost certainly the major European poet of the period after 1945.” That pronouncement has been repeated often over the past decade, as Celan’s poetry has come to greater attention in the United States through a fresh clutch of translations from the original German — translations that have inspired musical settings by various composers.

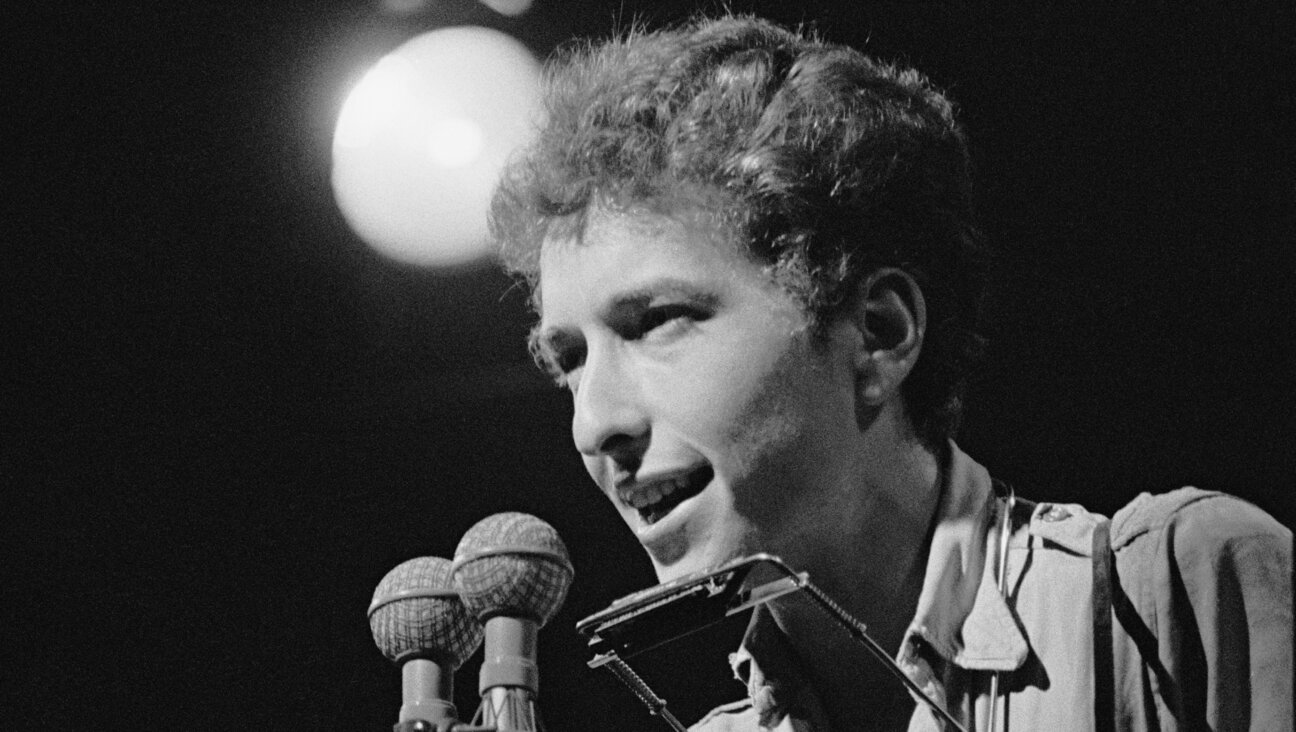

The most recent of these, “Force of Light” (Tzadik) by New York guitarist Dan Kaufman and his band, Barbez, calls to mind something else that Steiner once said: “The most important tribute any human being can pay to a poem or a piece of prose he or she really loves is to learn it by heart. Not by brain, by heart; the expression is vital.”

By that standard, “Force of Light” is an exemplary reading of Celan’s dark and deeply allusive work. And that is true even during those instrumental passages, when Celan’s words are left unspoken and Kaufman’s notes do all the talking.

First, some background: Celan was born Paul Antschel in Bukovina, a Hapsburg province that passed first to Romania and then later to the Ukraine. Both of his parents died in the camps — his father of typhus, his mother of a gunshot wound — where Celan himself spent nearly two years. After the war, he traveled to Bucharest and began publishing poetry in German under an anagram of his Romanian surname. He eventually settled in Paris, where he married and, in 1970, drowned himself in the Seine.

Celan was quickly recognized as one of the leading German-language poets of the postwar period. Yet his work remained relatively unknown in North America for many years, in part because comprehensive translations of his oeuvre were late in coming, and in part because of the notoriously difficult nature of his poetic language.

Despite his early work’s references to concrete objects and to historical events, there is also a great deal of wordplay and abstraction. His most famous poem, the chilling “Todesfuge” (“Death Fugue”), explicitly evokes the Holocaust. Yet Celan was extremely prolific, and much of his writing — especially his later poems, which grew increasingly spare and enigmatic — remains obscure.

All this appealed to Kaufman as a composer. Introduced to the poet in the 1990s by a former girlfriend, Scottish playwright and poet Fiona Templeton, Kaufman became transfixed by Celan’s work and began imagining a musical language that might capture the emotional wallop of his poetry.

In 2004, saxophonist and composer John Zorn invited Kaufman to produce an album for Tzadik’s Radical Jewish Culture series. Kaufman proposed a Celan homage, and Zorn, who had dedicated his own 1997 composition “Shibboleth” to the poet, readily agreed.

The resulting CD bears all the hallmarks of a classic Kaufman/Barbez production. There are starring roles for theremin and mallet percussion, rapid shifts in tempo and energy, and an enviable balance between compositional rigor and hard rockin’. But it is, understandably, more austere than anything the group has previously committed to disc.

“That wasn’t an intellectual choice,” Kaufman said in an interview with the Forward. “I wasn’t necessarily thinking of honoring the pain and suffering in a particular way, but it sort of came out that way. There are moments of straight rock, but there are other tracks that are very quiet. In a way, I think that was Celan’s last step — reaching toward silence.”

Given the ambiguity of Celan’s language, Kaufman decided to focus on the emotional resonance of his poems rather than trying to represent specific images through musical means. The result is a pervasive solemnity that runs like a dark thread through the entire album, from the elegant flourishes of classical guitar on the opening, “Shibboleth,” and the sober instrumental colors of “Corner of Time” to the coruscating theremin line on “The Sky Beetle.” Kaufman has Templeton herself declaim Celan’s verses sporadically throughout the CD, and deploying the poet’s terse images so sparingly only intensifies their impact. There is no singing per se — vocalist Ksenia Vidyaykina is no longer with the band — but Pamelia Kurstin’s quavering theremin more than fills that gap. The ethereal, otherworldly quality of her instrument — what Kaufman calls its “human wail” — perfectly suits the mood of the material.

Capturing the essence of Celan’s writing was not easy. “Force of Light” took three years to complete, and even now, Kaufman regards Celan’s poems as inherently resistant to any final or decisive interpretation.

“The more you come back to them, the more you can see them from six different angles,” Kaufman said. “I’m sure I’m misunderstanding things, but that’s the nature of art.”

Alexander Gelfand is a writer living in New York City.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO