EnviroJews Avant La Lettre

Woodbine, N.J.: Fifteen Acres and a Shul. Residents of the settlement in 1910. Image by COURTESY OF PHILADELPHIA JEWISH ARCHIVES CENTER IN URBAN ARCHIVES OF TEMPLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

When it comes to talk of sustainable agriculture and eco-Judaism, the history of American Jewry’s attempts to create an equally sustainable class of Jewish “agriculturists” has gotten lost in the shuffle. That’s a shame, because the story of how largely urban immigrants from Eastern Europe found themselves harvesting beans and cultivating chickens is a whopping good yarn, as well as a heartening tale of social uplift.

At a time early in the 20th century when thousands of impoverished immigrants sought a toehold in the New World, philanthropically minded organizations such as the Baron de Hirsch Fund made a point of getting them onto the land. Tilling the soil, it was widely believed, would not only relieve the congestion of the immigrant neighborhood, but also transform the neighborhood’s “alien” residents into able-bodied, hard-working Americans at one with the natural order. An experiment in social engineering designed to stand on its head the widespread notion that a Jew with a hoe was an unnatural creature, the efforts of the Baron de Hirsch Society and its offshoot, the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society, seemed so novel, so downright improbable, that the contemporary, non-Jewish press had a field day, filling its pages with detailed accounts of life on the farm.

With barely contained amusement, it wrote of the “well-ordered” and “cleanly” characteristics of Jewish farming communities, of “rosy children everywhere” and of the absence of Yiddish signage — a pointed contrast to Manhattan’s Lower East Side in virtually every respect.

Eager to make the case that farming was a “peaceful way of life,” the Baron de Hirsch Fund set its sights on Woodbine, N.J. That rural and southernmost part of the state “for some occult reason, has been the site of an unusual number of social and sociological experiments,” The New York Times reported in 1902. But the reason for establishing a farming community or “colony,” as it was commonly called, in that neck of the woods was not too hard to find: Woodbine was bound to the affluent seaside communities of Atlantic City and Elberon, N.J., as well as to the greater metropolitan area by train — the West Jersey and Seashore branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad — making it easy to get its bushels of grapes, corn, cabbages and fruits to market.

From that perspective, Woodbine made good economic sense. But the well-intentioned folks at Baron de Hirsch — no farmers, they — didn’t reckon with the sandy, swampy and inconsistent soil or, for that matter, with the swarms of mosquitoes that tormented the locals every summer. (“The mosquito output is simply beyond the power of measurement,” an eyewitness related in 1912.) They also didn’t reckon with the fierce show of independence demonstrated by Woodbine’s feisty residents, who were quick to complain about this, that and the other thing. The community’s archives, which can be consulted at the American Jewish Historical Society, are filled to the brim with laments: about the weather, lackluster crops and the officious ways of the colony’s administrators. Chafing under the latter’s heavy-handedness and elaborate web of rules, residents sometimes took matters into their own hands. In 1909, when the

Baron de Hirsch Fund nixed the idea of showing movies, fearful lest their putatively salacious content undermine Woodbine’s moral integrity, disgruntled residents, signing their names in Yiddish, got up a petition in protest. Ultimately, the powers that be bowed to the “wishes of the people” and agreed to hold occasional movie screenings, provided that a committee composed of both locals and administrators would vet the films’ content.

In the end, the farming life was no match for the movies and other perquisites of modernity. Despite the “homely blessings that agriculture bestows on its votaries,” as one enraptured champion would have it, the Jewish agriculturist was unable to keep his offspring down on the farm for too long. City life, and its manifold possibilities, beckoned alluringly, rendering most Jewish farming colonies a one-generation phenomenon. All the same, Woodbine and thousands of its counterparts throughout the nation deserved their day in the sun. While they lasted, these enterprises not only contributed materially to America’s bounty, but also underscored the Jewish community’s commitment to improving the lives of its members, and its collective belief in the regenerative possibilities of the soil.

Click here to see images from the Philadelphia Jewish Archive’s exhibit “Woodbine, Jew Jersey: Fifteen Acres and a Shul”

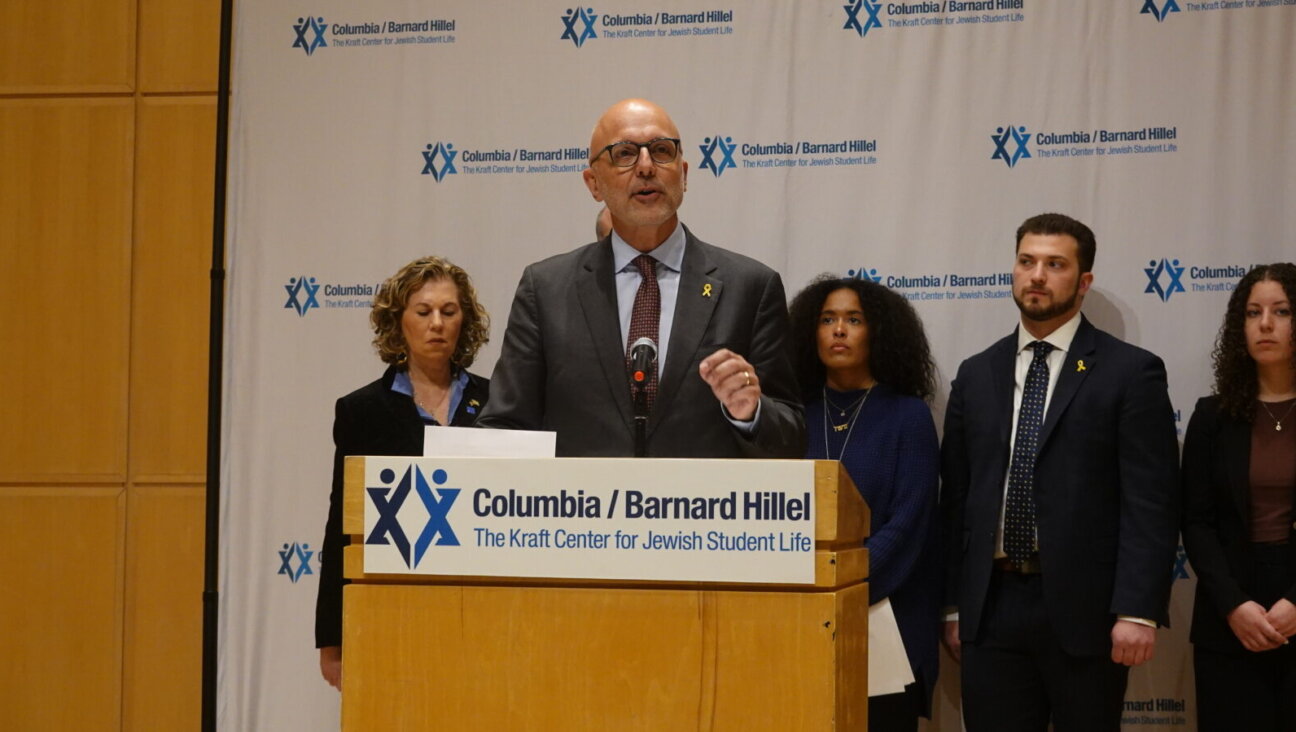

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30