It’s Off to the Races With a Jockey Named Cohen

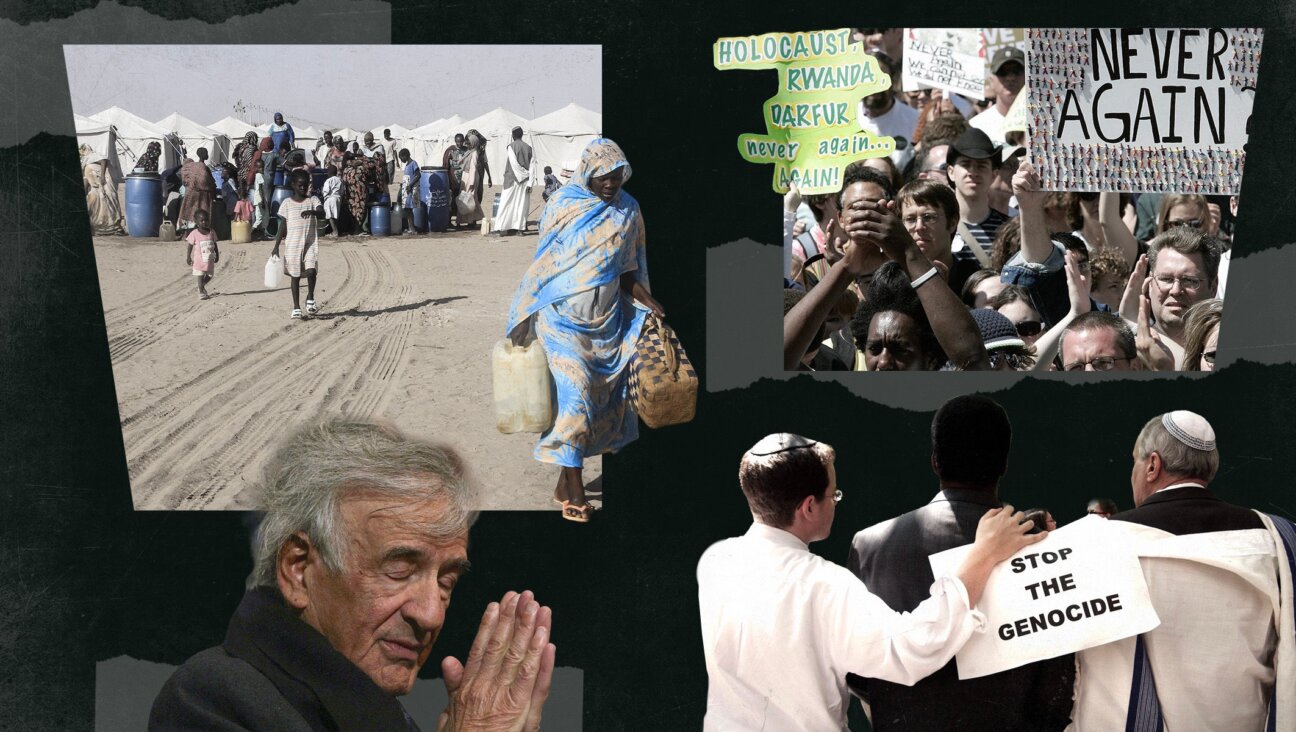

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Not Horsing Around: David Cohen, one of only a few Jewish jockeys, rides Malibu Moonshine to the starting gate at Aqueduct Racetrack. Image by John Barnes

It’s the sixth race at New York’s Aqueduct Racetrack, and David Cohen is rounding into the home stretch on the back of a black filly named Beautiful Pear. He is crouched over her, the both of them gray from splattered dirt, his whip slapping furiously at the filly’s right shoulder as they battle toward the grandstand.

The pair is game, but the horse fades, finishing 13th in a 14-horse field. It’s but a momentary setback for Cohen, 25, a Jewish jockey who has made his name on minor tracks and now hopes to prove himself on the New York circuit.

So far in 2009, Cohen has ridden to victory more times than all but three American jockeys. After dominating a six-month meet at Delaware Park in Wilmington last summer, he and his agent have decided to take on some of the best jockeys, trainers and horses in North American thoroughbred racing at Aqueduct Racetrack.

“It’s a big jump to go from riding in a place like Delaware to coming here,” said Andy Serling, a racing commentator for the New York racing circuit’s on-track TV channel. “In what I’ve seen with him coming here, he’s got a lot to learn.”

Serling’s skepticism notwithstanding, Cohen has acquitted himself well during the first weeks of the Aqueduct fall meet. He has eight wins in 61 starts, placing him among the track’s top seven jockeys.

One recent Thursday morning, Cohen arrived at Aqueduct’s sprawling barn complex, home to 480 horses, at 6:25 a.m. Cohen rides as many as six horses per morning, sometimes seven days a week, in the hopes that

the trainers will ask him to race their mounts in the afternoon. As he was boosted into the saddles, trainers asked Cohen to take the horse a certain distance in a specific amount of time. He was off by no more than a second.

Accompanying Cohen was his agent, Bill Castle, 45, who spends his days building Cohen’s racing schedule, making sure his dance card is filled with the right sorts of matches. While Cohen galloped, Castle watched from the backstretch rail with a trainer named David Jacobson. As Cohen rode by, he greeted the trainer, shouting: “Mr. Jacobson! Shalom!”

All three men are Jewish, but none seems eager to make a big deal of it. They aren’t hiding their faith, but it’s clear that casual antisemitism plays a role on some tracks. Jewish jockeys are rare here, but not unheard of. Horsemen often mention Walter Blum, a Hall of Fame jockey who won the Belmont Stakes in 1971, and Cohen says he once attended a dinner for retired Jewish jockeys, but these are exceptions.

Surprisingly, the New York circuit is also home to Maylan Studart, a 20-year-old Brazilian-born Jewish jockey. Before coming to New York, Studart rode at Florida’s Calder Race Course, where being Jewish helped her develop relationships with trainers. “We used to kid around that I had the Jewish connection,” she said.

Chest-high in their multicolored silks, some jockeys resemble skinny munchkins. Cohen, on the other hand, who is 5 feet 6 inches tall and 115 pounds, has the finely controlled limbs of a dancer. The faint impression of wispiness is dispelled by his handshake, which is like that of a Marine.

Cohen was introduced to racing by his father, an owner and breeder in Southern California, and learned to ride horses by “breaking babies” — training his father’s young thoroughbreds to take a rider. He started his career as a jockey when he was 19, riding throughout California. This year marks his first foray into New York racing.

Throughout the morning, Castle keeps an iPhone to his ear, writing frantically on a ream of paper carried under his arm. While some of the agents hanging around the barns look like classic horsemen with ruined fedoras and grizzled faces, Castle retains shades of the stockbroker he was until four years ago. After an illness, Castle left Wall Street to dedicate himself to what he calls “the game.” There’s a hint of Allan Sherman in his round and jovial face, but he’s all business when selling his jockey.

“David’s just physically strong,” Castle said.

Cohen thrives in the last few seconds of the race, when the horses need to be convinced to keep up their speed as they head for home. “When they get tired and they’re no longer strong, you got to pick up that 1,200 pound animal and get him to the wire,” Cohen said. “You got to literally pick his head up and push it.”

Cohen also holds himself as a master in the art of the whip, a 30-inch-long cushioned crop with a “popper” at the end. He said he knows “how to hit a horse properly, when to mix it up… going left hand, going right hand, back left, flagging him by his face, shoulder.”

To maintain his weight, Cohen eats carefully. He learned weight management from a retired jockey named Laffit Pincay Jr., who ate a single peanut for breakfast every morning. Pincay taught Cohen to speed-walk rather than run in order to avoid putting on too much muscle.

At 9:30 a.m., when his workouts are done, Cohen heads to Long Island’s Atlantic Beach, where he has rented a home for the duration of the meet. The day’s racing will not start for three more hours, so he uses the time in between to feed his pit bulls and see Maria Charles, a jockey with whom he has a 2-week-old baby boy. On an empty trackside road on the way to the highway, Cohen drives his Lexus like a jockey: really, really fast.

New York’s racing circuit consists of three major thoroughbred tracks, which take turns hosting racing meets throughout the year. “All the best jockeys in the world come out to Saratoga,” the circuit’s premiere track, said Dan Silver, director of communications and media relations at the New York Racing Association. Belmont Park also draws top talent, although it competes for the biggest jockeys with other major meets that coincide with its run.

Aqueduct, so close to John F. Kennedy International Airport that landing planes interrupt conversations, is far from Saratoga’s Gilded Age splendor and Belmont Park’s easy grace. The track’s decrepit and cavernous grandstand — built, expanded, and renovated between 1959 and 1985 — looks cobbled together and forgotten. The racing here, which runs straight through from late October until April, isn’t at the level of the other two New York tracks. Top trainers, horses and jockeys are drawn elsewhere during the winter months, leaving New York to the hungry and hearty jockeys willing to brave subzero morning workouts and freezing racing days.

Cohen will be staying behind, hoping to make his mark. He seems nonplussed by the pressures of Aqueduct. The young father has spent the past five years working toward this meet. “There’s plenty of time in life to have fun and party,” he said. “Right now, you got to focus.”

At times, however, he exudes a certain wistfulness about the life he’s missing. “I’ll probably always like horseracing, but there are a lot of other things I like about the world,” he said. “I’d like to own a restaurant. Something like that. A nice Jewish deli.”

Still, he has no plans to quit. “Right now, this is making money and paying the bills, and I definitely have a true passion and love for it.”

Contact Josh Nathan-Kazis at [email protected].