Israel’s Naked Truth

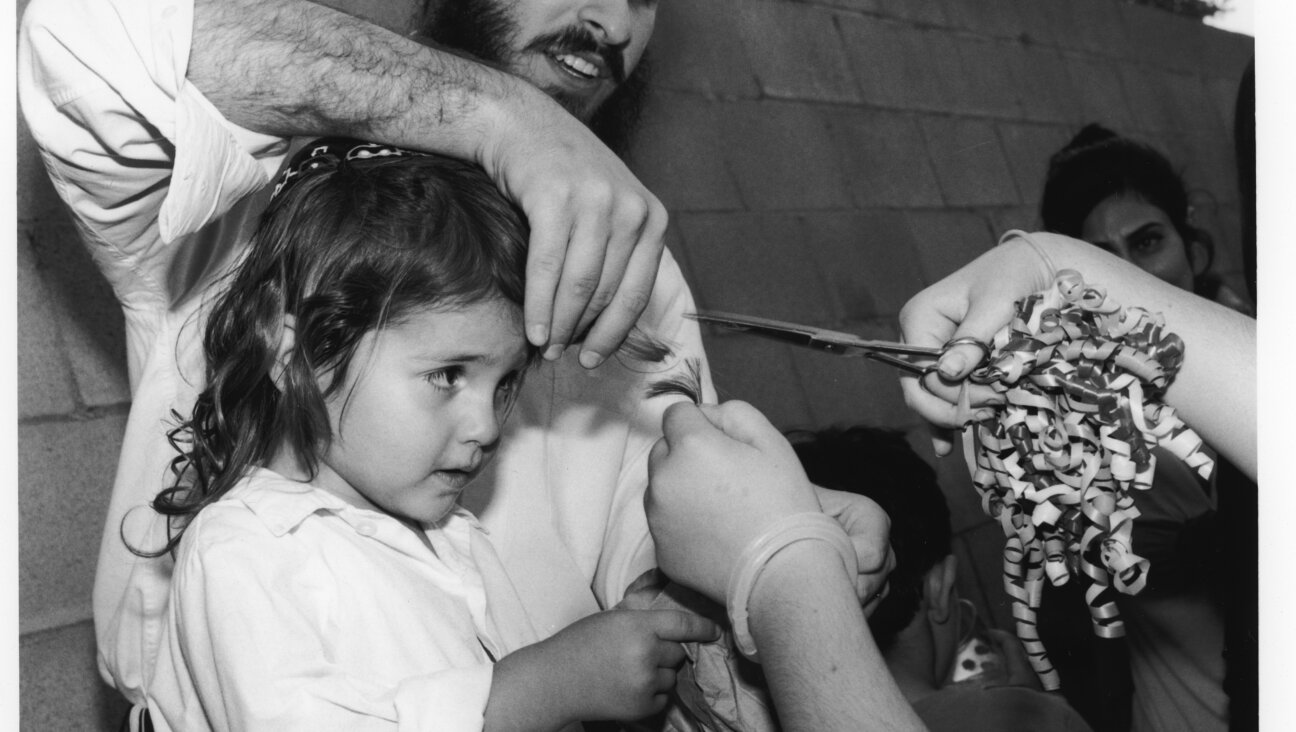

King of Achziv: Eli Avivi discusses his life, loves and photographs (such as the one at top) in his own independent kingdom. Image by COURTESY OF THE ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL

Image by COURTESY OF THE ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL

Documentary film is a sprawling, big tent of a genre. Any topic could, conceivably, be made into a documentary. But I’ll venture a semi-controversial opinion: It shouldn’t.

What do I mean by that? Well, not everything is best said within the visual, dynamic medium of film. A good, if not great, documentary will intrigue and captivate its viewers. But a bad documentary, one that bores viewers, does a spectacular and gratuitous disservice to both the viewers’ time and the subject at hand — assuming, of course, that the subject is worthwhile and lends itself to filming in the first place.

King of Achziv: Eli Avivi discusses his life, loves and photographs (such as the one at top) in his own independent kingdom. Image by COURTESY OF THE ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL

Despite those cautionary words, most of the documentaries at the Israel Film Festival, being held in New York City through December 13, get it right. Three documentaries, in particular, should not be missed by viewers interested in engaging filmmaking on quintessentially Israeli subjects.

“The Shakshuka System” is a damning film about the tangled and interwoven interests of big money and Israeli government. Director Miki Rosenthal, a well-known Israeli investigative journalist, focuses on the affluent Ofer brothers, who bought privatized assets from the government in highly profitable yet highly suspicious transactions. The film’s factual expositions are cleverly handled in interstitials made to look like a Monopoly set, all while clearly conveying that the statewide, systemic problems detailed in the movie are anything but a game.

It would be easy to deem Rosenthal the Israeli Michael Moore, but to do so would be wrong. Yes, it’s true that Rosenthal’s combative, in-quarry’s-face-with-camera style will seem familiar to viewers of such films as Moore’s “Roger & Me.” Similarly, Moore and Rosenthal share the somewhat arrogant demeanor of a boorish crusader who sees himself as a modern Jeremiah, prophesizing and filming in a righteous attempt to expose society’s blemishes.

The analogy fails, though, because of the terms of scale. Rosenthal’s work is much more gutsy than Moore’s, because the Land of Israel is so damn small. Being a Hebrew-speaking investigative journalist inherently limits your audience and job prospects. But the audience becomes all the more limited when your documentary’s subjects buy the television channel that employs you while you are making a movie about them. If pissing off the big fish in the big pond is bad news, then surely pissing off the big fish in a small pond should make you consider flying lessons. Rosenthal is holding fast, though, despite lawsuits currently filed against him by the Ofer brothers. The film’s appearance in this festival is somewhat shocking in light of these facts, and should be seen on principle in order to support free journalistic inquiry in Israel. But it happens to be a genuinely intriguing film, shining a light on dubious activities in a way that I’d argue is crucial to the future of journalism in Israel, if not to free inquiry in Israel itself.

The second good film, “Achziv, A Place for Love” illuminates an Aquarius-like time and place in Israeli history. Eli Avivi, a young Israeli, opted out of the get-a-haircut-and-get-a-real-job scene just after the state’s independence in order to become the self-appointed ruler of Achziv, a former Arab village turned free-love kibbutz of sorts. With ample hashish, nude photography and (surprise!) sex, Achziv became an oasis of lascivious decadence in a country of comparatively straight-laced mores. Prominent Israeli writers Yoram Kaniuk and Yehuda Amichai spent formative time in the throes of its joys and (ahem) natural beauty in the days before AIDS. Avivi, a photographer, has a vault of thousands of artistic photographs of naked young Israeli women. (Hey, it’s good to be the king!) The film, directed by Etty Wieseltier, confronts the past with the present, as 50- and 60-something men and women look at the people they used to be. It’s a jarring counterpoint to the more conventional Zionist narrative, and it’s pleasantly and decadently human as a result.

The third recommended documentary is comparatively sexless (“Achziv” is a tough act to follow, in fairness). Nor does Regev Contes’s film deal with big business, like Rosenthal’s. Instead, its subject is a three-man insurance company, memorably deemed by Contes to be “The Worst Company in the World.” He should know: The company belongs to his dad, Karol Contes. Run from Karol’s apartment, the company’s three men sit around and goof off all day, and are then shocked when they’re headed toward bankruptcy. Karol’s two employees are his brother, Latzi, whose genius has been enlisted to shred documents, and Moshe, whose incompetence extends to everything except a remarkable propensity for narcolepsy. Enter Regev, who decides to take some time off from directing commercials and help them get the company back on track — making a highly amusing film along the way.

The film is “The Office” plus Israeli guys with attitudes: a winning combination. “Employees” spend more time plying the office cat with coffee, taking him to his vet visits and cooking authentic Czechoslovakian mashed potatoes than making sure that insurance policies are filed on time. But what catapults the film to near excellence from fun is the conflicted, love-tainted amusement and sadness of Regev, who also serves as the narrator, for his subject: his father. There’s nothing detached about this film, nor should there be: It’s about as un-objective a documentary as could be made. And as a result, the film is not only about what makes a company fail or succeed, or what makes men ambitious or lazy. This film is about what makes us love our parents regardless of who they are, or perhaps even despite it.

That idea brings me, inevitably, to a discussion of one more film, and my own mother.

I watched “Voice of Jerusalem,” Yehoram Gaon’s exposition of the bleak future of Israel’s capital city, over the Thanksgiving weekend, when Horn family members tend to congregate. Hence, my mother watched the film with me.

It should be noted at this point that my mother is neither a cineaste nor a diplomat. At first she kept her thoughts, though accompanied by ample eye rolling, to herself. After 15 minutes, she started muttering audibly, “This movie is so long.”

“Mom, it’s not that long.” (For the record, it’s 68 minutes.)

“It sure feels long.”

Silence. Two more minutes.

“This whole film needs an editor,” she opined as yet another Gaon interview went long, sprawling, undirected, into the unforeseeable future. “Does this film even have an editor?”

“In all likelihood, yes, Mom.”

“Well, that person didn’t work very hard, because aren’t you sitting here like me, thinking, ‘Stop talking!’” she gestured to poor, unsuspecting Gaon on my flatscreen.

“I’m trying to hear what he’s saying,” I said.

“Well, good for you,” she said to me. “Because I’m thinking more along the lines of, shut up already!’”

Mom’s not going to the Cannes Film Festival anytime soon, but her point exemplifies my earlier one about documentaries. When portraying as well trodden a subject as Jerusalem, for example, you should avoid using footage that looks like it was taken from a traffic helicopter, as well as clichéd school-filmstrip music. Instead, do as the previous three films did: Use something genuine, heartfelt and original, and ask good questions in interviews, which are then edited for effect. If you don’t have good footage and sound, then perhaps you should be making something other than films from your material.

Mom listened to a section of Gaon’s argument to an angry Palestinian that Gaon’s family belonged in Jerusalem (one of the few genuine and provocative moments of the film).

“I’m ready to kick this narrator guy out of Israel myself,” she said, and stood up to leave.

“And yes,” she said to me, preemptively. “Feel free to quote me.”

And I did.

Jordana Horn is a lawyer and writer at work on her first novel.

Watch the first few minutes of “Achziv, A Place for Love”:

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

- 3

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 4

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Survivors of the Holocaust and Oct. 7 embrace at Auschwitz, marking annual March of the Living

-

Fast Forward Could changes at the FDA call the kosher status of milk into question? Many are asking.

-

Fast Forward Long Island synagogue cancels Ben-Gvir talk amid wide tensions over whether to host him

-

Fast Forward Trump mandates universities to report foreign funding, a demand of pro-Israel groups

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.