A Ghostly Trace of the Jewish Occult

A Prayer: A text fragment from a ceremony held in the 18th or 19th century and recovered from the Cairo Geniza. Image by Courtesy of The University of Manchester

A newly discovered piece of stained, wrinkled paper conjures up the details of a Jewish exorcism that appears to have been performed sometime in the 18th or 19th century.

A Prayer: A text fragment from a ceremony held in the 18th or 19th century and recovered from the Cairo Geniza. Image by Courtesy of The University of Manchester

The ghostly document details the prayers that were performed on Qamar bat Rahmah to try to rid her of the spirit of her dead husband, Nissim ben Bonia. According to the handwritten but well-preserved Hebrew text, the rabbis asked the ghost to “leave this woman, Qamar bat Rahmah, [and forgo] all authority and control that it has over her; and Nissim ben Bonia shall have no more authority and control whatsoever over Qamar bat Rahmah in any form or manner at all.”

The 150-word text provides a haunting insight into the often forgotten world of the Jewish occult. While exorcisms are frequently described in Jewish texts from the Middle Ages on, this appears to be the first text that provides the prayer used in a specific exorcism.

“It has names, and you can kind of speculate as to some sort of story lurking behind the names,” said Yossi Chajes, an expert on Jewish magic and mysticism at the University of Haifa who was not involved in the unearthing of the text. “It’s an unusual document.”

The document fittingly comes from the abandoned recesses of the Cairo Geniza, a storeroom attached to a Cairo synagogue in which hundreds of thousands of ancient texts were left because of the Jewish prohibition on destroying religious documents. The storeroom and its contents were discovered in the late 19th century and were made famous through the scholarly work of Solomon Schechter.

Some of the geniza’s collection made its way to the University of Manchester, in England, where the exorcism text was found while Renate Smithuis, a researcher, was cataloguing the 11,000 items there. When she shared the text with an Israeli colleague, Gideon Bohak, who is an expert in Jewish dybbuks, or spirits, she realized the significance of her discovery.

“We got a bit excited because we realized that people have collected lots of dybbuk stories, but our fragment describes a real event, where you see how they come together and pray in order to exorcise the ghost from a widow,” Smithuis said.

The prayer makes a number of things clear. At the time of the exorcism, Qamar bat Rahmah is married to Joseph Moses ben Sarah and is bothered by the spirit of her late former husband, Nissim ben Bonia, and the “control that it has over her.” The prayer is respectful to ben Bonia’s spirit and asks that when it leaves his widow’s body, it “shall go and reunite with his [vital] soul, his spirit and his [rational] soul in the place which is appropriate for them.”

The document is evocative, with its wavy handwriting, and its brown smudge on the bottom — but it does not contain much information to determine where or when it was used. The documents found in the Geniza came from a span of more than a thousand years (including original documents written by Maimonides).

Smithuis and Bohak believe that the exorcism of Qamar bat Rahmah probably took place in the 18th or 19th century because most of the documents that ended up in Manchester are concentrated in that time period. In addition, Bohak found that the incantation on the document matches up almost exactly with a prayer recited by Rabbi Shalom Shar-Abi, the famous Jerusalem kabbalist, which was recorded in a book published in 1843.

Chajes, the Haifa scholar, said that exorcisms of dead spirits became particularly prevalent in the Jewish world after the 16th century thanks to the popularity of Kabbalah, with its discussion of reincarnation and the transmigration of spirits. In Egypt and the rest of the Mediterranean, Chajes said, most exorcisms went through a number of common steps. They would begin with a minyan of men reciting psalms, before moving onto the blowing of a shofar and the incantation of prayers written to coax the ghost out. While in Eastern Europe, a ghost was often referred to as a dybbuk, in Sephardic lands a ghost was more commonly referred to as a ruach, or spirit.

“The bottom line is that these

things were generally done according to an established pattern,” Chajes said. The primary curiosity for Chajes in the new finding is that it contains little distinctively mystical or kabbalistic phrasing.

Smithuis and Bohak have written an article about the finding that is set to appear in an upcoming book from Oxford University Press about the Geniza collection in Manchester. Smithuis said that of all the documents she has combed through, this one has a special hold on her.

“I can just imagine the widow being still quite sad about the loss of her first husband, and then maybe, I don’t know, being considered deranged by her new husband,” Smithuis said. “I don’t quite know how to think about it psychologically, but obviously it makes you imagine all kinds of things.”

Contact Nathaniel Popper at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

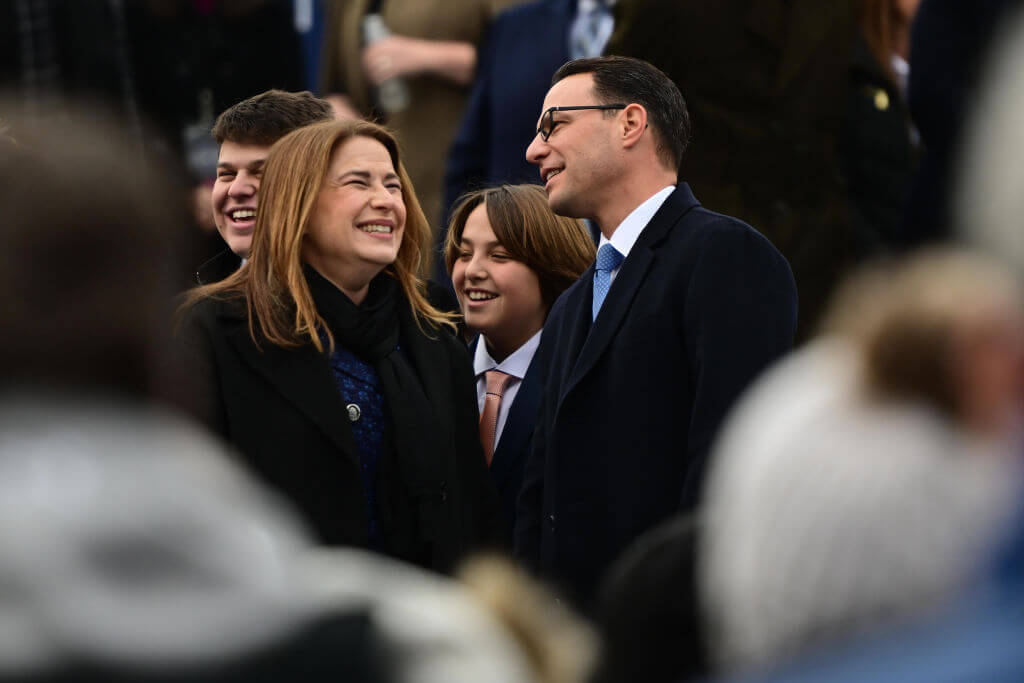

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Jewish family killed in New York plane crash

-

Fast Forward Israelis can no longer enter the Maldives after Palestinian-solidarity ban goes into effect

-

News Harvard is defying the Trump administration — after its own crackdown on academic freedom

-

Opinion The Passover attack on Josh Shapiro was terrifying. But don’t assume it was antisemitic

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.