The Parody’s Over: Whither Our Era’s Mickey Katz or Allan Sherman?

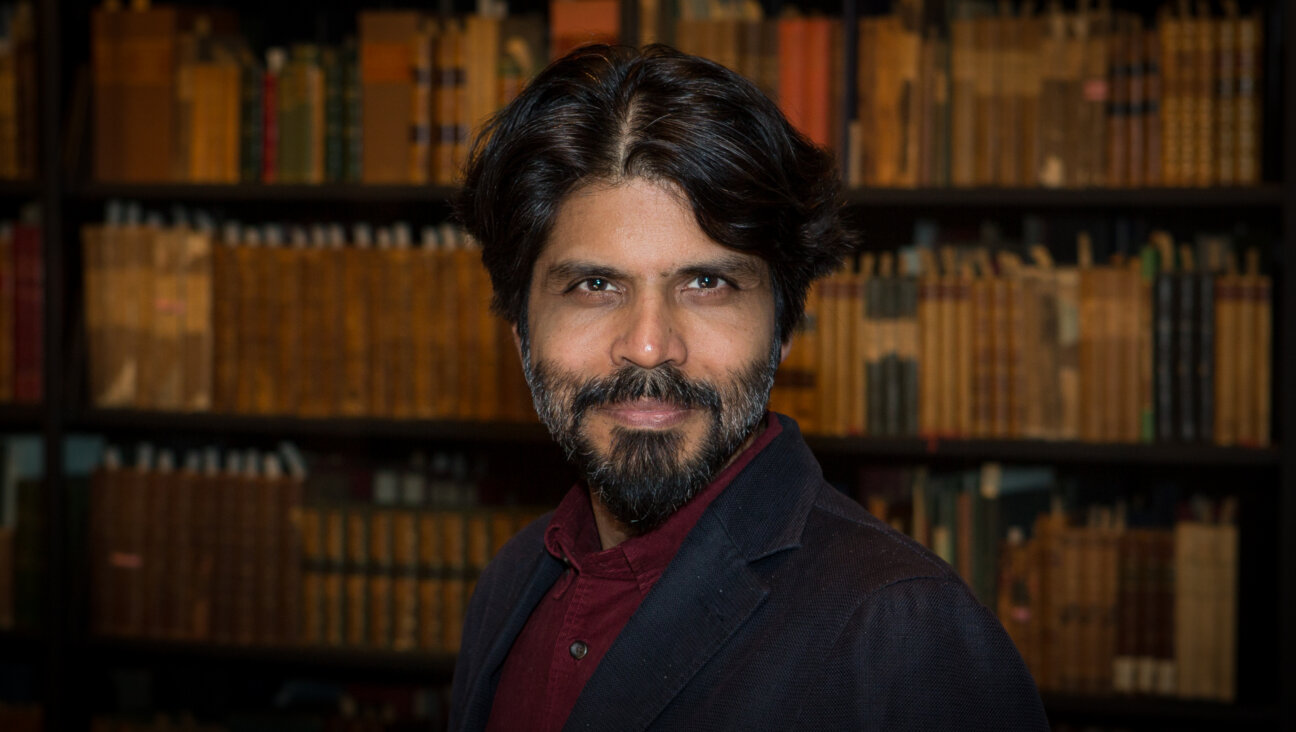

Allan Sherman

In the 11 months since it was released on YouTube, Leah Kauffman’s parody of Justin Timberlake, “My Box in a Box,” has been viewed more than 4 million times. Her “I’ve Got a Crush…on Obama” — out since June 2007 — has been hit close to 5 million times.

Allan Sherman

Like Kauffman, Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, “Reno 911” and “The Simpsons,” bless them, have done what they can to restore parody to its once prominent position in American comedy. Nevertheless, their welcome success cannot hide the fact that at the movies, on television and on the radio, parody is just not as big as it was. While there is a lot of funny stuff going around these days, there just isn’t as much good, old-fashioned parody.

Especially Jewish parody. I’m sensitive to this, because my house, on the other hand, is loud with Jewish parody, old Jewish parody. My older daughter (age 6) likes Allan Sherman; my younger (age 3) likes Mickey Katz. Although my girls don’t get most of the jokes, they do sense, with the unsettling insight of children, that something pretty interesting is going on.

I’ll admit that I didn’t discover Katz until late in the game. In 1983, I found a copy of “Borschtcapades” in a secondhand store on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. My folks would never have gone for anything so overtly Yiddish, but they did buy other things. I remember three records from the early 1960s: Vaughan Meader’s great parody of the Kennedys, “The First Family”; a Harry Belafonte collection, and Sherman’s “My Son, the Folksinger.” The calypso kick didn’t last very long, and “The First Family” got shelved quickly after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. But I must have listened to “My Son, the Folksinger” a lot, because 40 years on, I still know the lyrics by heart. And needless to say, I also grew up on Mad magazine.

My kids are therefore the children of a child of what seems — from this distance, at least — like the golden age of Jewish-American parody, a period whose arc begins somewhere around the Marx Brothers’ wonderful travesty of “Il Trovatore” in “A Night at the Opera,” and comes to an end in the early 1980s with “Airplane!” and “Naked Gun.” It is not limited to film, of course, but occurs in all genres and media — in cartoons, in music, in stand-up and on TV. Mostly irreverent, usually relevant (or topical, at least), classic Jewish-American parody milked that hyphen for all that it could: It played the Jewish off the American and, when it could, the American off the Jewish. Sometimes, the Jewish won.

If puns are the lowest form of wit (and they’re not), then parody is the lowest form of humor (and it isn’t). The distinction between wit and humor is a little rough, but at least it’s serviceable: Wit is about intelligence and language play; humor is about personality and identity, about self-delusion and foible. A witty joke involves an unexpected turn of phrase and invokes intelligence; a humorous one involves verbal pratfalls and lampoons shortsightedness. Some jokes, of course, are witty and humorous all at once.

Parody seems simple. You take an established genre or, better still, a well-known song or poem or plot, and you rewrite it. In the process, you make use of its most recognizable traits to make fun of it, usually by revealing its pretensions. Jewish-American parody is no different. In the type of parody that I grew up with, non-Jewish forms are stuffed full of Jewish content with complicated, amusing results.

Sherman took “Frère Jacques” and turned it into “Sarah Jackman,” a clipped and oddly endearing telephone conversation about the achievements and tsoris of a large Jewish family (“How’s your brother Bentley?/Feeling better ment’lly/He’s nice too/He’s nice too”). The tune remained the same, but the ambience certainly changed. Katz took Davy Crockett, the backwoods Cold War hero of Disney fantasy, and turned him into “Duvid Crockett, King of Delancey Street.” Again, same melody, different intent. Disney’s Davy is anything but a schlemiel: Katz’s is nothing but.

Katz’s usual shtick began with something that seemed quintessentially American, like the myth of the West or something that was too obviously faddish. He then loaded it up with Jewish food and exploded it with klezmer. Katz showed — in his language, in his musical style and in the narratives he transposed with a laugh — that Jews lie just outside full Americanization. They talk funny, they eat funny and they listen to funny music.

Sherman was up to something else: He celebrated Americanization. He did this implicitly in his biggest hit, “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh” and explicitly in numbers like “Harvey and Sheila.” The latter is an ode to Jewish upward mobility, and ends patriotically with “This could be/Only in the USA.” Here, Sherman reversed the usual procedure of Jewish-American parody by stealing the tune, not of an American hit, but of “Hava Nagila.” He thereby turned the theme song of Zionist youth groups into a paean to the American dream and into a pitch for the Diaspora. Even at his most Jewish, Sherman’s Yiddishkeit was limited to some Yiddishisms (“How’s by you?”), some cracks about food and frequent nods to lower-middle-class Jewish preoccupations. The Jews in Sherman’s songs are not all that different from other Americans, and it’s not surprising that Sherman was remarkably successful in non-Jewish markets: He was reassuring, and he showed assimilation at work.

In the end, classic Jewish-American parody — whether it’s Katz or Sherman, Mel Brooks or Woody Allen — is the flip side of assimilation. Both parody and assimilation come down to mimicry: Assimilation is mimicry that dares not speak its name. Parody is mimicry that not only admits what it is but also makes a virtue of doing it badly.

In its fractured reflections on what it takes to be mainstream culture, classic Jewish-American parody patrolled the boundaries of identity and tested the rights and the rites of entry. That’s why Mad had such appeal; it recast the particularly Jewish predicament of Americanization as the general plight of adolescence. Mad’s spoofs were the products of Jewish cartoonists who thought like prematurely cynical, wise-ass 12-year-olds. Though the magazine zeroed in on the oddities and inconsistencies of the adult world and not on the idiosyncrasies of the goyish one, Mad threw in the occasional Yiddish word just to make sure you got the point.

At its best, classic Jewish-American parody transformed its audience’s dilemmas into sheer manic energy. Unlike the spritz of the Jewish stand-up or even the harmless insults of a Henny Youngman and a Don Rickles, the touchstones of Jewish parody are not particularly aggressive. Their anger, such as it is, is usually masked by the tummler’s goofiness. Listening to Katz’s inspired insanity, you would not guess that at some level, “Duvid Crockett” betrays a marked ambivalence about assimilation. Nor would “Harvey and Sheila” immediately strike you as having anything to do with the odd but often-noted contradiction of mainstream American Zionism: the fact that we live here, not there. The conflicts and psychological costs of Americanization might have generated classic Jewish-American parody, but they got expressed more clearly elsewhere — in that great shande far di goyim, “Portnoy’s Complaint.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that classic Jewish-American parody really didn’t survive into the 1980s. The ragged edge of the assimilating process had largely disappeared by that point, and so this particular flavor of parody lost its mediating purpose. Interestingly enough, though, Sherman’s work has recently been re-released, and Katz has come back, too, particularly for those who are working to rediscover the Jewish difference that Americanization tried to neutralize. Perhaps, then, Kauffman’s parodies come at us from the other side of assimilation. Despite the gauzy scrim of nostalgia that still envelops it, the golden age of Jewish parody looks like it could offer a path back to the kind of secular Yiddishkeit whose loss forms the bass note of Sherman’s and Katz’s work.

For my daughters, however, none of this is a problem, at least not yet. They are hearing something different and much livelier in the silly voices and bumptious humor of their favorite singers. They are getting a hint of the sanctioned tumult, the wild rumpus of anarchism, which, as Gershom Scholem claimed, lies at the very heart of Judaism.

David Kaufmann teaches literature at George Mason University.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.