Obey Civil Law, Say New Orthodox Kosher Rules

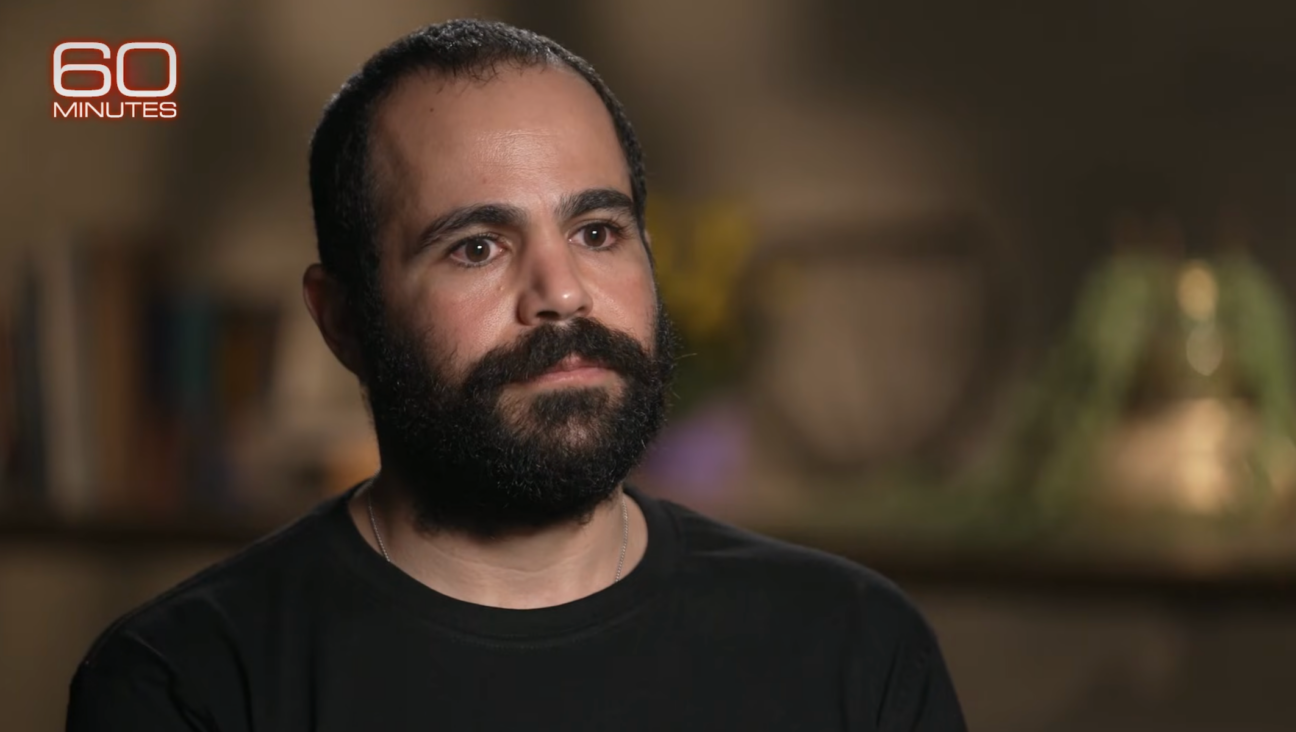

Seal of Approval: Rabbi Morris Allen leads the Hekhsher Tzedek effort. Image by Beth Jacob Congregation

The crimes that brought down the Agriprocessors kosher meat company and could put its owner, Sholom Rubashkin, in jail for life, still reverberate. An echo was heard in the Rabbinical Council of America’s January 21 announcement establishing a set of ethical guidelines for how agencies supervising kosher food production should behave beyond ensuring that the laws of kashrut are observed.

Seal of Approval: Rabbi Morris Allen leads the Hekhsher Tzedek effort. Image by Beth Jacob Congregation

The RCA, representing more than 1,000 Orthodox rabbis and closely affiliated with the Orthodox Union, by far the largest certifier of kosher food, is the latest Jewish organization to respond to the Agriprocessors scandal, which exposed widespread violation of immigration laws, child labor laws and financial fraud.

In a three-page memo, the RCA recommended that agencies involved in supervising kosher slaughter now needed to show “fidelity to both ritual practice and the rule of civil law.”

The new guidelines boil down to one added responsibility to the job of the mashgiach, or kosher supervisor: If federal or state law is being broken, the company’s products will be denied certification. As obvious as this rule might seem, observers say it is a departure for the kosher agencies, which previously saw themselves as concerned exclusively with the halachic intricacies of ritual slaughter and food preparation.

“In the wake of the Agriprocessors debacle, it was clear that everyone’s expectations were all out of alignment,” said Rabbi Asher Meir, chairman of the task force charged with drawing up the guidelines. “What the producers felt was expected of them was in one place. What the agencies felt they were expecting of the producers was in another place. And what the consumers were expecting was somewhere else entirely. It was necessary to make some order and align the expectations and decide what standards should be appropriate and that they be transparent to everybody involved.”

The fact that the new standards are United States law has allowed the RCA’s guidelines to gain wide approval. But others who seek more far-reaching change in the conditions under which kosher food is prepared — though they applaud the move — worry that they do not go far enough.

Meir, however, defended the new guidelines as having been written precisely to avoid overreaching.

“Are we undertaking to supervise something beyond that the food is kosher? The answer is no,” he said. “That’s not what we’re asking people. Are we setting specific guidelines for good conduct? The answer is also no. The standard that is being demanded in the RCA guidelines is law-abiding behavior. We are not making a new standard, a new bar above and beyond what the laws and regulations require.”

But there have been attempts at a “new bar,” most notably the Hekhsher Tzedek program, now embraced by the Conservative movement. Launched in 2007, also as a response to the Agriprocessors violations, a commission of rabbis came up with a set of very specific requirements — from wages to working conditions to health insurance and maternity leave policies — that would earn a company a seal of approval, or Magen Tzedek.

The guidelines were laid out in a first draft that began circulating in September for the sake of eliciting comment. They go far beyond simply adhering to the law and are an attempt to infuse social justice principles into the production of kosher food.

Morris Allen, the rabbi who founded the project, sees the RCA principles as an affirmation of a conversation he says he first started.

“I think it’s an endorsement of our work and it’s a result of our work,” Allen said. “It may not be a direct endorsement. There are clearly nuanced and substantive differences. But ultimately it’s a far cry from people saying two years ago that there is nothing about ethics in the production of kosher food. They said kosher food is just about whether it’s prepared according to the ritual law. We have moved far from there.”

Still, Allen said, he has questions about how the RCA is going to enforce its guidelines. Unlike Hekhsher Tzedek, which demands that producers prove they are in compliance in order to receive the hechsher, or approval, the RCA guidelines are reactive, and their effect will be apparent only when supervising agencies decide that certain misconduct demands withholding certification.

Others interested in putting the ethics of workers’ rights on par with food production also worry that the RCA is not going to positively change the current environment.

Shmuly Yanklowitz is the founder and co-director of Uri L’Tzedek, an Orthodox social justice organization that has focused attention on the condition of workers at kosher restaurants, giving out its own “ethical stamp,” the Tav HaYosher, to those that are free of “abuse and exploitation.” According to Yanklowitz, 30 restaurants have already received the seal.

“I think that the RCA standards help to move the community in the right direction by considering these issues, but we need to move from theory and broad ethical standard to precision and accountability,” Yanklowitz said. “Any standards without accountability and full transparency will carry very little weight.”

Yanklowitz also added that there was a Jewish context for including employee rights as part of the concept of kashrut, pointing out that Jewish law prohibits the oppression of workers.

It is the broadness of the RCA guidelines, though, that has gained it such ringing support from those who had been opposed to more activist efforts like those of Hekhsher Tzedek.

“The Hekhsher Tzedek certification was not about secular law or Halacha at all. It sought to enforce social norms like ‘just wages’ and fair treatment,” said Rabbi Michael Broyde, who wrote critical articles about Hekhsher Tzedek for the Forward and was part of the RCA task force that drew up the new guidelines. “It never focused on American law at all. This proposal is grounded in enforcing American law.”

An even harsher critic of Hekhsher Tzedek was Agudath Israel, the Haredi Jewish communal organization. When the proposed rules for receiving the Magen Tzedek were first discussed in September 2008, the group put out a statement harshly denouncing them as “misguided and misleading” and likely to foster “a distorted understanding of kashrus, and a corruption of the halachic process itself.”

The new RCA ethical principles have been greeted very differently.

Agudath’s view now, according to Avi Shafran, a spokesman for the organization, is, “The guidelines seem a responsible way of addressing nonkashrut-related lapses in the kosher food industry.”

Contact Gal Beckerman at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.