Brandeis Professor Explores ‘Sex and the Shtetl’

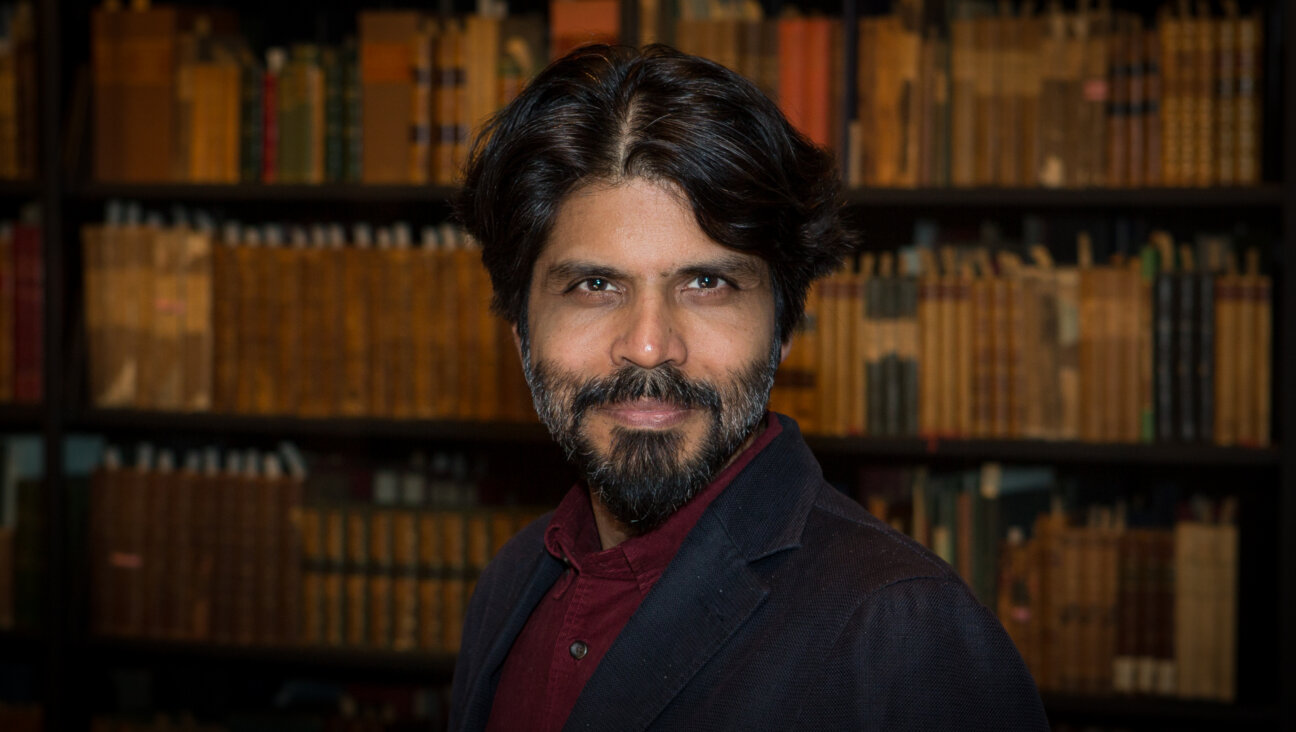

Freeze: Her first book focused on jewish marriage and divorce in Russia. Her next book will further explore sexual norms in the region.

The timing could not have been better. When ChaeRan Freeze completed her coursework toward a doctorate in Russian Jewish history in 1993, it was just as the doors to the archives in Moscow and St. Petersburg were beginning to swing open. As a result, she was among the first to request long-untouched troves of material — material that later formed the backbone of her dissertation: a groundbreaking study of Jewish marriage and divorce in imperial Russia.

Freeze: Her first book focused on jewish marriage and divorce in Russia. Her next book will further explore sexual norms in the region.

But viewed with a little distance — today, Freeze is a Brandeis University professor of Jewish history and is in the middle of a yearlong research fellowship at Harvard University — the timing of her first visits to the Russian archives was but one of the fortuitous twists to have informed a remarkable life and career.

The first came almost two decades before she completed the doctorate work. In 1975, when Freeze (née Yoo) was 5 years old, her father, a doctor, moved the family to Ethiopia from South Korea, thinking he’d spend a year or two offering humanitarian aid; the Haile Selassie regime had just been topped by a Marxist-Leninist junta. But the one or two years turned into 30, and Addis Ababa became ChaeRan’s home base. Though she attended English-language missionary schools, there were relatively few foreigners around — and even fewer Jews. (Not until she left Ethiopia and moved to the United States did she learn of Operation Moses and Ethiopian Jewry.) Nonetheless, it was in Ethiopia that her interest in Judaism took root. At a piano recital, an American diplomat offered her a cassette of Israeli music and suggested that she look at the novels of Chaim Potok and Leon Uris, which she was able to find in her school library. The reading proved life changing.

“I fell in love with the characters,” she told the Forward by phone from her home in Belmont, Mass. “I could relate to the minority culture. Had I found Asian American novels or stories, perhaps I may have taken a different path, but these were the books I found.”

In 1987, Freeze began attending college at the University of California, Irvine. Though she had relatives nearby, campus life was jarring. “I found myself in an uncomfortable position,” she said. “I was immediately seen as Asian American, and I wasn’t. I didn’t relate to that whole culture.” She felt more at home with the campus’s international students — and its Jews. And though the school had no formal Jewish studies curriculum, she began studying Hebrew and sought out Jewish topics in papers she wrote for courses on German and Russian history. As she explored different topics, it became clear to her that an academic career in Jewish studies was the path she wanted to take. After a three-month stay on an Israeli kibbutz, she began graduate work at Brandeis.

Though Freeze was the only non-Jew in the program at the time, she quickly proved herself. “I had a higher bar to reach, and my adviser, Jehuda Reinharz, was very strict,” she said. “I had to work hard to show that I could be a Jewish historian.”

She succeeded. “There are lots of students who have studied Judaica here who are not Jewish,” said Reinharz, president of Brandeis since 1994. “In that sense, she is not an exception. What does distinguish her is that she’s incredibly bright, a very hard worker and has great facility with languages. Whether she’d gone into this field or any other field, she would have been a great success. She’s a scholar’s scholar.”

And her scholarship has been nothing if not provocative. In her first book, “Jewish Marriage and Divorce in Imperial Russia” (2001), she argued that shtetl life was hardly the stuff of myth. Jewish divorce rates in 19th-century Russia, she showed, far outpaced those of the population as a whole. In her second book, which she hopes to complete in two years, Freeze is looking to further explore Jewish sexual norms, bringing to bear information culled from medical pamphlets, advice books, court records — “Jewish neighbors were quite a surveillance tool; they had no qualms about reporting to the courts about all sorts of imagined or real illicit affairs,” Freeze said with a laugh — and the relevant responsa literature from rabbis. The book’s provisional title offers a nod to TV character Carrie Bradshaw: “Sex and the Shtetl.”

After finishing her degree in 1996, Freeze — who in 1994 married Gregory Freeze, a professor of Russian history at Brandeis — taught for a year at SUNY-Binghamton before Brandeis hired her back. Though neither she nor her husband is Jewish, she is raising her two children, ages 8 and 6, to be what she calls “domestically Jewish.” They observe the Sabbath and study some Torah each week.

“I was comfortable with my mixed-up chameleon identity when it was just me,” she said, “but raising children it’s so much more difficult. They’re at an age where they’re questioning. They want the ‘right’ answer, the Soviet answer.”

Conversion is something she has considered. Indeed, scholar that she is, it is something she has probed deeply.

“I teach a whole class on conversion to and from Judaism,” she said. “I’ve taught it three times now. Every year, I get into the halachic debates and the history of conversion. The more I study it, the more daunting it is for me. I’m on a journey. I’d hope that at the end of this journey, I’d be worthy of conversion.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

- 4

Opinion Mike Huckabee said there’s ‘no such thing as a Palestinian.’ It’s worth thinking about what that means

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Film & TV In this Jewish family, everybody needs therapy — especially the therapists themselves

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.