Schnorientalism: The Tao of Jews

As even the most tenuous speaker of Chinese can tell you, travels in that country mean having the same Inevitable Conversation over and over. And over.

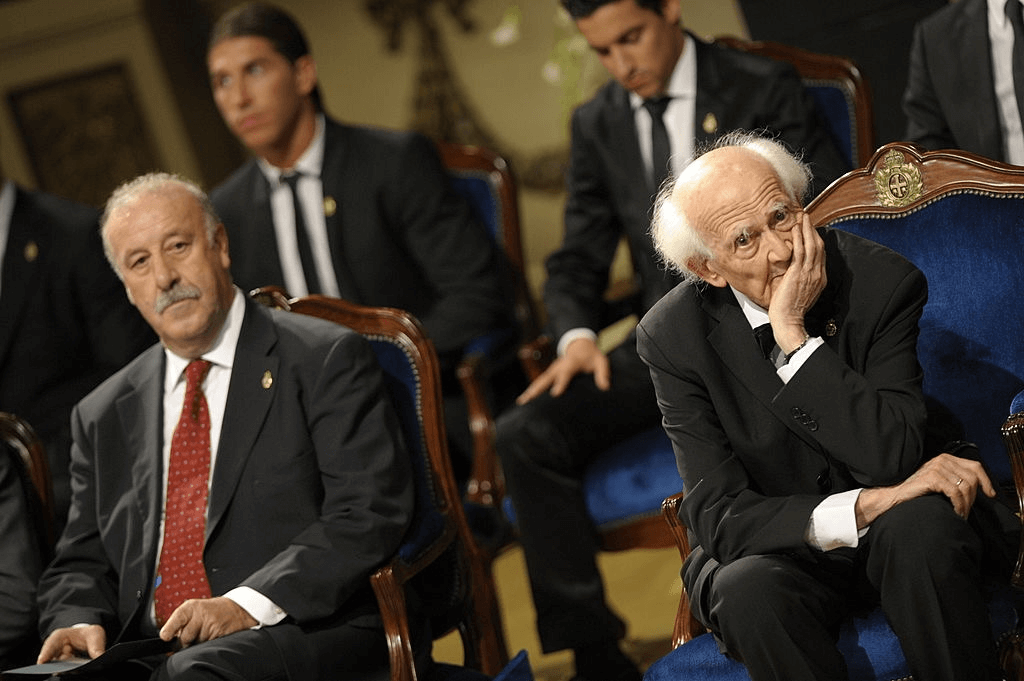

Mao and Friend: Joining the Chinese Communist Party as a foreigner required direct approval of the Politburo's highest-ranking members. Sidney Rittenberg, above right, was among the few outsiders who joined the party.

Bridge Position: The Jews of Kaifeng are the only remaining link to China's distant Jewish past. Above, a model of the Kaifing Synagogue, which was built in 1163.

“Oh!” the locals will pretend to swoon. “Your Chinese is excellent!”

“No, no,” comes your polite or honest reply. “It’s really nothing.”

“Where are you from?” “What is your salary?” “Are you married?” “What do your parents do?” “What are you doing in China?”

Of the literally hundreds of times I’ve gone through this routine, one exclamation — usually around the “Who are your ancestors?” part of the conversation — has come up often enough to raise an eyebrow: “Oh, Jewish! Very clever! Very good at business!” So nu?

Full disclosure: I am not, strictly speaking, Jewish. Not that my Chinese interlocutors care; I can explain all I want about a New York upbringing, guilt, bagels and Reform recognition of patrilineal descent, but such nuances often get lost in a response as deafening as it is sudden: “Very clever! Very good at business!”

“But,” I protest, “those are other Jews. Really! I’m terrible at business! I’m not here to despoil you from my position at the apex of the world economy! I want to study history and —”

“So clever!”

“No, Woody Allen — ”

“So good at business!”

“But Trotsky — ”

“Very clever!”

“Sigh.”

Nor are the Chinese alone. During World War II, a cabal of Japanese generals styled as “Jewish experts” designed the secret (and ultimately unrealized) “Fugu plan” to harness the Jews’ financial sorcery by rescuing refugees from Europe and resettling them in China’s occupied northeast. (The arms of the Japanese were never entirely open to begin with: The plan took its name from the Japanese blowfish, the delicacy that is lethal if incorrectly handled.) On a Mongolian train, an inquisitive Buddhist gentleman pointed to my brain with an effusive thumbs-up.

This much is clear: Most of Asia lacks the “killed our Savior” chip so firmly lodged on Western Christendom’s shoulder, and shares such values as education and prosperity. “Controlling the world’s banks,” the thinking goes; “What’s wrong with that? We would if we could.” Money might be part of the explanation: It’s certainly true that many East Asian well-wishing phrases for holidays heavily emphasize “wealth” and “prosperity,” where Westerners might invoke “love” and “happiness.” But in China, Jewish cachet seems especially pronounced, and there’s a good deal more to the Jewish story in China, and the Chinese stories of Jews.

Anecdotal evidence abounds for some strange Jewish-Chinese cultural axis across the ages. Unprompted, an ethnic Chinese woman in Vietnam compared her people to the Jews; another in Thailand did the same. Within China itself, the city of Wenzhou’s business-savvy reputation has led to such book titles as “The Fearsome Wenzhounese: China’s Jews,” a sentiment echoed in my Beijing classroom and in casual conversations beyond. Bookstores abound with “Financial Success the Jewish Way” and similar titles. Even back in the States, a Chinese friend en route to a lecture referred to the speaker as “some Jewish guy.” “Well,” I asked, “how do you know that?”

“He has a Jewish name.”

I bristled: “What do you know from Jewish names?”

Her response was as irritating as it was bulletproof: “Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, Solomon Brothers….” Sigh.

Moreover, it seems like my friends were more or less correct that their Chinese diaspora constitutes the “Jews of Asia.” From Hanoi to Bangkok to Jakarta and beyond, the merchant classes are overwhelmingly peopled with well-educated ethnic Chinese whose connections to the homeland and each other — the “Bamboo Network” — constitute a huge business advantage. They are also, like the Jews, periodically expelled (from Vietnam), repressed (under Indonesia’s Suharto) and rioted against (in Malaysia, Thailand and really everywhere else). Like Jews, they are fiercely proud of their heritage, assimilating somewhat while maintaining temples that assert identity. With so many similarities — which extend to the immigrant clichés of “Eat, Eat,” and demanding that their sons become doctors — it shouldn’t be too surprising that Chinese people find a certain resonance vis-à-vis the Jews with whom they come into contact. And with so many roving Jews over the past few millennia, the odds were decent that at least a few would wander into one of the world’s most powerful and ancient civilizations. And wander in they did.

The first recorded settlement of Jews in China dates from the ninth century, when some Silk Road merchants schlepped into the Song Dynasty capital of Kaifeng and settled down. Intermarriage led to near-total assimilation, and the synagogue was lost to the sands of time (and floodwaters of the Yellow River), but despite the loss of nearly all Judaic languages, books and customs, some in Kaifeng still consider themselves Jews. China’s reasonably benign policies toward statistically insignificant and politically low-profile minorities (for example, not Tibetans) have even led a dozen or so descendants to file for official minority status, which brings special protections and exemptions.

The next notable Jewish jaunt in China came with the 1840s, when a Baghdad-born Sephardi named Elias David Sassoon moved to Shanghai from British Bombay. The Sassoons made a fortune in matzo — just kidding! It was opium — and invested in the Shanghai real estate market, then better known as “rice paddies.” By the early 20th century, patriarch Victor Sassoon was throwing bashes, building a world-class hotel and quipping with the best of them: “There’s only one race greater than the Jews, and that’s the Derby.” His chutzpah notwithstanding, anyone who laid eyes on Shanghai’s opulent waterfront architecture would be hard pressed to disagree. Other Sephardic families, like the Hardoons and Kadoories, also dominated business in Shanghai, leaving a dizzying array of real estate and business interests whose footprint remains, despite the past few years’ redevelopment frenzy.

Pogroms and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 brought floods of Jewish and/or Russian refugees to Shanghai’s open port, with a similar flow passing through the far northeastern city of Harbin (the childhood home of Ehud Olmert’s father). Later, as the Holocaust engulfed the Jewry of Europe, a few courageous Chinese and Japanese consular officials defied orders from home and granted desperate Jews passage to Shanghai. The city’s Japanese occupiers interned some 20,000 Ashkenazic Jewish arrivals in a ghetto but refused requests from their German allies to kill or hand them over, owing perhaps to the ultimately unsuccessful Fugu plan. With the war’s end in 1945 and the approaching communist takeover of 1949, Shanghai’s Jews began to leave the country. The wealthy Sephardic Jews fled for British Hong Kong (which sports a Kadoorie Avenue to this day), while the Ashkenazic refugees mostly left for England, Australia, the United States and the emerging State of Israel.

Over these near-dozen decades of heavy Jewish presence in Shanghai, not a few ethnically Chinese Jews were sired. (Among these is my nonobservant Jewish step-grandfather’s London acupuncturist, a fact that bore the following exchange: “What time shall we say next week, Dr. Chang?” “Sorry, Mr. Cohen, it’s the High Holy Days.” “What?”). But by the mid-1950s, there was scant remainder of Shanghai’s disparate but flourishing Jewish community besides a handful of Chinese Jews in the outlying district of Hongkou — that and one of Asia’s earliest and most dramatic skylines, a testament to the Sephardic Jews’ ruthless business prowess and a powerful symbol of what Jews meant to the Chinese collective memory.

Besides businessmen and refugees, China has played host to another Jewish paradigm: the radical bourgeois intellectual. Joining the Chinese Communist Party as a foreigner required direct approval of the Politburo’s highest-ranking members (Mao Zedong and friends) and among the few outsiders who joined the party, became Chinese citizens or were permitted to live in China, the Jewish presence sticks out like a sore thumb. Sidney Shapiro, Sidney Rittenberg and Israel Epstein were the best known, and while none of these lefty expatriates was particularly influential either as a Jew or a communist, their mere presence in Beijing reinforced a panoply of clichés enunciated in everything from Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” to Allen’s wife. (Rittenberg, who now runs a corporate consulting firm, seems to have lost some of his Red zeal, though that probably has as much to do with his 16 years in solitary confinement as with his Jewish business acumen.) While the foreigners were comfortably put up in the Beijing Friendship Hotel (or, depending on the political winds, doing hard time), the Chinese people suffered one catastrophe after another, so impoverished and battered by half-baked economic schemes and destructive political campaigns that when Mao’s death finally ushered in market reforms, moneymaking was ready to swing back into fashion. Kvelled Deng Xiaoping, “To get rich is glorious”; with China’s opening, legions of foreign investors — including you know whom — poured in.

Interesting enough — but how, you might ask, does this all connect to the “very clever” routine? Or, for that matter, Jews’ own clichéd predilections for mah-jongg, mu shu and the odd Asian girlfriend?

Throughout Chinese history, the actual Jews were sufficiently few and high profile that they’re not hard to trace. Chinese conceptions of Jews today — and vice versa — aren’t always as clear. One important concept in Chinese society is diwei, or status, and it is expressed by forms of address, protocol in table manners and myriad other everyday social interactions. Besides chatty curiosity, the purpose of the Inevitable Conversation is to gauge your diwei through the normal indicators (salary, education, marriage status). Intelligence and moneymaking ability are highly respected, and if Chinese people know that you’re Jewish — even if you insist you’re here to study literature or observe rare tree ants or overthrow capitalism — it may nonetheless give your diwei a boost.

Challenge this all you like, but they’ll just shrug: “Well,” they say, “I was simply always told that Jews are smart and good at business.” And indeed they were; moreover, it’s a prejudice irrelevant to their everyday lives, not to mention that any Jews whom an average Chinese might meet are liable to be students or businessmen — not exactly the demographic to subvert the “Clever! Good at business!” stereotype.

Said students and businessmen, moreover, are illustrative of the disconnect between China’s Jewish past — littered with scholars and schnorrers, rich and poor, roustabouts and refugees, colorful types like Morris “Two-Gun” Cohen — and China’s staid Jewish present. The modern Jewish population is largely severed from the past: almost entirely expatriate, secular, and indistinguishable from other foreigners. Visible assertions of Jewish identity are generally restricted to the odd Chabad House or event at the Israeli Embassy, while China itself — pork juice in your vegetables, sir? — is not very hospitable to observant Jewish tourists. Outside of a few major cities, you won’t find a minyan for hundreds of miles in any direction, unless you count Israeli backpackers, who are probably too stoned to pray anyway.

The Jews of Kaifeng are the only remaining link — a tenuous one — to China’s more distant Jewish past. And they weren’t even known as such; instead, the Chinese called them “Blue-Hatted Hui,” or just another type of Chinese Muslims (not such a stretch when you consider that both groups eschew pork, worship one God, wear tiny hats and are Abraham-affiliated).

As China’s modern Jewish landscape is fairly barren, so are historical sites just that: historical, with scarce culture or community that can claim direct descent back to the earliest Jews in China. Players of the “Oh, is he/she/it Jewish?” parlor game will find anecdotes galore — Kaifeng, Shanghai, Rittenberg, “We’re the Jews of Asia!” and more — but you can’t connect the dots. If you weren’t playing the Jewish parlor game, you likely wouldn’t notice a thing, except a Shanghai synagogue or two.

Skepticism firmly in mind, a friend and I stumbled across the Shanghai Jewish Studies Center. We could hardly believe what we found: a Hebrew-speaking Chinese girl, a recent college grad, with an interest in Judaism that tended irresistibly toward fetish. The conversation was Manhattan-meets-Brooklyn, Upper West Side vs. Crown Heights:

“Hi! Thanks for coming! Sorry, my English isn’t so good. How’s your Hebrew and Yiddish?”

“Uh,” we stammered, dumbfounded, “we… don’t… speak…”

“I’ve been to Israel twice. How many times have you been?”

“Actually… we’ve never…”

Before we could steer the conversation back to Trotsky, Freud and Heeb magazine, she had already revealed her ambitions to marry a Jewish guy and move to Israel, and as we perused the contents of the office, she explained how she had learned Hebrew at the only university in China that teaches it. Seeing a Chinese with such an acute interest was equally informative and mystifying; because, really, what the hell? Here we’d been trying our best not to read too much into anecdotes, to avoid the “Who’s Jewish?” parlor game myopia, and then this girl hit us in the face with so many inverted stereotypes that we were rendered nearly speechless (too speechless, in retrospect, to get her phone number).

So what’s really going on here? Lifetimes of research and the writing of weighty tomes should precede any final pronouncement, and it would surely be a disservice to two of the world’s most ancient cultures to render a crude summary. But here goes: Jewish history in China is interesting but not too special; after all, Jews scattered all over the world and did all sorts of interesting things. Taken together, the parallels and encounters are undoubtedly striking; but, the connection between China’s Jewish past and Jewish present is dubious. The American Jewish love affair with mah-jongg and mu shu — to say nothing of the famous lefty Jews living in Mao’s Beijing — lacks any meaningful connection to Kaifeng or Shanghai. The Jewish clichés of preordained doctor or lawyer careers are common to many American immigrant cultures, to say nothing of “Eat! Eat!” So nu? I’m not sure — but, if the Jewish parlor game is your thing, you can certainly do worse than China. In fact, you may want to visit anyway: The chow mein is excellent, and there’s mah-jongg every night.

Nick Frisch is a writer in Taipei. He studied Chinese language and history at Columbia University.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Opinion Stephen Miller’s cavalier cruelty misses the whole point of Passover

- 3

Opinion I co-wrote Biden’s antisemitism strategy. Trump is making the threat worse

- 4

Opinion Passover teaches us why Jews should stand with Mahmoud Khalil

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture Jews thought Trump wanted to fight antisemitism. Why did he cut all of their grants?

-

Opinion Trump’s followers see a savior, but Jewish historians know a false messiah when they see one

-

Fast Forward Trump administration can deport Mahmoud Khalil for undermining U.S. foreign policy on antisemitism, judge rules

-

Opinion This Passover, let’s retire the word ‘Zionist’ once and for all

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.