The Sieges of Gaza

Siege 1: Israeli sources are in perfect accord: The flotilla was a provocation, intended less to bring humanitarian aid to the people of Gaza, more to break Israel’s siege. The people on board the vessels made no effort to disguise their intentions. Accordingly, Israel knew in advance that it would be faced with a more difficult challenge than simply intercepting six boats and turning them away from Gaza and toward Israel’s port at Ashdod.

Now, however, Israel seeks to have it both ways: If it knew in advance that a provocation was intended, why was it surprised when its commandos, boarding the ship one at a time as they rappelled from helicopters, were assaulted? Did the Israeli authorities imagine that the provocation would be limited to the singing of “We Shall Not Be Moved?” that they were dealing with people trained in and committed to passive resistance? That cannot be: Israel has a full dossier describing one of the main groups involved in the flotilla, the Turkish Foundation for Human Rights and Freedom and Humanitarian Relief. Israel believes that the IHH, as it is widely known, is a radical Islamist group masquerading as a humanitarian agency, even claims it is sympathetic to al-Qaeda.

Now, if Israel knew all this beforehand, why did it choose to play directly into the hands of the provocateurs? Why did it accept its assigned role in a drama so frontally evocative of memories of British commandos taking over ships laden with Jewish refugees, survivors of the Holocaust bound for what was then still Palestine? Is the Israeli leadership so amnesiac that it failed to see the obvious connection? And is it so dense as to have been unable to understand the consequences of the probable downside to its operation, or so smug because it is now a member of the OECD and has all those miracle drugs in the works and all those tantalizing startup high-tech companies? What universe do these people inhabit?

Those questions are not entirely rhetorical. The response they require goes to the question of alternatives. What, if anything, might Israel have done to avoid being sucked into the role of villain in a script carefully prepared by others? In 2002 and again in 2009, Israel boarded ships carrying arms for Hamas without firing a shot. The difference this time, presumably, was the presence of so many — some 600 — passengers aboard the ship. But that is exactly the point.

Perhaps a formal independent inquiry will explore what alternatives there were, will not limit itself to the tedious excuses put forward by the Israeli government and its parrots in the American Jewish community. But even if it does go beyond explaining — or explaining away — what in fact transpired, it is unlikely to confront the underlying issue, the issue that has now, all the excuses notwithstanding, provided so signal a victory to the murderous gangsters of Hamas.

That issue, of course, is the siege of Gaza.

That siege is ostensibly meant to prevent the introduction into Gaza of materiel and equipment that Hamas might use to attack Israel. Given Hamas’s record, it is entirely reasonable for Israel to respond with stringent control over what may be imported, whether by land or by sea.

Siege 2: But something more is plainly going on here. While the list of permitted imports is arbitrarily re-arranged with some frequency, it is rather difficult to accept the military uses to which cilantro, potato chips, nutmeg and notebooks, a small sampling of prohibited goods, might be put. Toilet paper yes, fabric for clothing no; lentils yes, dried fruit no. And so forth.

Plainly, the nature of these lists — their precise content is incomprehensibly a military secret — indicates something more than, and more sinister than, a straightforward attempt to limit the military capability of Hamas, Israel’s sworn enemy.

We do not have to look far for an explanation. In 2006, even before Hamas defeated Fatah for control of Gaza and before Hamas took the young Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit, captive, Israel’s policy was summed up by Dov Weisglass, an adviser to Ehud Olmert, the Israeli prime minister: “The idea is to put the Palestinians on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger,” he said. The restricted diet was intended to turn the residents of Gaza against Hamas. Now four years, many rockets and a war later, with Shalit still in prison, it has become clear that the continuing punishment of Gaza’s people by Israel has, if anything, strengthened Hamas, and intensified the bitterness toward Israel of Gaza’s population. In short, the siege in its current form is not working. It has neither weakened Hamas nor liberated Shalit. And, because its immediate target is a civilian population, it must be defined as a form of collective punishment.

Now, collective punishment is defined as a war crime by the Fourth Geneva Convention, adopted in 1949 and accepted as part of customary international law in 1993. But what the international community had in mind in employing the term were actions far more draconian than are here at stake, actions such as murder and torture, albeit also corporal punishment. Partisans may claim that the “diet” of Gazans is a form of corporal punishment, but it is not my intention here to assert a legal category. I intend, instead, a common sense definition: When innocent people are systematically deprived of benign available goods by a hostile power, we are witness to collective punishment.

Israel’s perfectly reasonable refusal to allow the importation of war-related materiel and equipment is sapped of its legitimacy and moral status by Israel’s overreach, by its essentially frivolous, hence abusive, exercise of power. A world that would likely readily accept the legitimacy of blocking the import of arms does not and will not accept the legitimacy of putting the people of Gaza on a diet.

Under the circumstances, including the Mavi Marmara episode, Israel will not be able to persuade the world that its actions are meant to enhance its security unless it radically restates its intention and radically changes the nature of its blockade. In effect, that is what the international community is now demanding, more or less stridently. It is altogether too easy for Israel to shrug its shoulders and complain that it is being judged by a double standard, that the whole world is anyway against it. It is considerably harder to explain why cilantro is not permitted.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

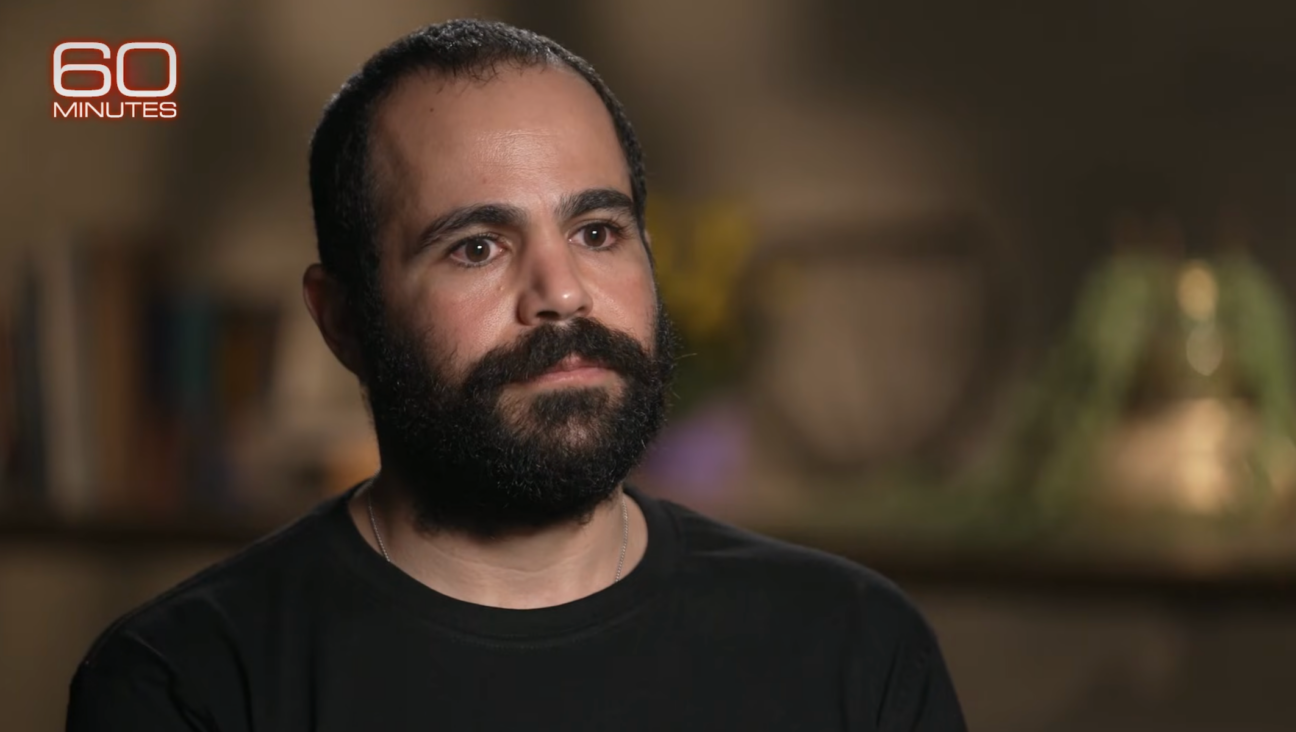

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.