Of Folk, Faith and Famous Father-in-Law

Peter Himmelman is an eclectic musician who has earned critical accolades for everything from his television show scores to his folk-rock albums. His work scoring the TV series “Judging Amy” garnered him an Emmy nomination in 2002, and just a few months ago, his latest children’s album, “My Green Kite,” was nominated for a Grammy. “The Pigeons Couldn’t Sleep,” Himmelman’s 10th studio album, was released last summer. If that all sounds like enough, it isn’t: Himmelman is currently scoring the Fox series “Bones” and ABC’s “Men in Trees.”

The 48-year-old Santa Monica resident grew up in Minneapolis, where he began his musical career while still in high school. One of his earliest collaborations, the new wave band Sussman Lawrence, recorded two albums before Himmelman went on to a solo career. Since then, Himmelman has successfully navigated the waters of multiple, often wildly different, genres and come out rocking in all of them.

Oh, and he also happens to be Bob Dylan’s son-in-law.

Himmelman recently fielded some questions from the Forward.

Why did you decide to expand into children’s music?

I have four children of my own, and so as they were growing up, it was very natural to me to sing for them and make up songs and stories for them. At one point, a company in the Midwest contacted me and asked if I’d be interested in making a record for children. As every artist knows, there’s nothing more motivating than a deadline and a fee, and so when I got both those things, my first kids’ record, “My Best Friend Is a Salamander,” came into being. I’ve since made four more.

What are the challenges of writing in so many different genres? Does it ever get musically confusing, so to speak, or do the different genres inform one another?

As a rule, I thrive when I’m doing several different projects at once. It doesn’t get confusing for me because I’m able to focus my attention to whatever task is at hand. It’s difficult to explain, but there is a radically different feeling when I go about making music for children as opposed to making music for adults. The same truths are existent in each, but perhaps similar to the way one talks to a child versus the way he would speak with an adult, the metaphors, expressions and context need to be appropriate for each. A third facet of what I do — aside from performance, which is its own unique universe — is composing for film and television. It’s another perspective, which really requires me to adopt a service mentality. That is to say, when I’m making my records, they are really expressions of my personal vision. When I’m composing to picture, I’m primarily serving the needs of the director or the producers. The structure created by helping another person achieve their goals can be very liberating.

How would you define your level of Jewish observance?

I’m not too comfortable with labels in general, but I suppose you wouldn’t be far off if you characterized me as an Orthodox or observant Jew.

Have you always maintained a high level of observance? How were you raised?

I was raised in a home that was very Jewishly aware. My grandma spoke Yiddish, we were very Zionistic and I attended Hebrew school. We went to a Conservative shul in a suburb of Minneapolis. I started becoming more observant in 1986 while living in New York City.

How does your religious observance affect your music?

Since I write mostly about my observations — as opposed to fictional accounts — the prism through which I see the world most definitely affects the music I make.

How has it affected your career?

There have been many missed opportunities to further my career. I’ve turned down several “Tonight Show” engagements and some major tours, but it’s important to remember that nobody forced me to turn these things down. I did it all of my own volition, and though there was a price to pay, I believe that the rewards I continue to get from having success on my own terms have been well worth any short-term sacrifices.

Does being an observant Jew in any way conflict with your role in pop culture? Can they co-exist peacefully, so to speak?

I don’t think I have a role in pop culture. All my roles are played out in my family life and in my community. It would be disingenuous of me to say that I have any role in or any allegiance to pop culture. In fact, it’s something I try to protect myself and my family from. If you mean to ask, can an observant Jew be an artist and make a living creating things, the answer in my opinion is yes, of course. There is no conflict in that.

What do you think of the Matisyahu phenomenon?

I like Matisyahu both as a musician and as a person. I think he’s an extremely talented person who, like any real artist, is on a quest. I’m always anxious to see where it leads.

Given that your father-in-law is Bob Dylan, has he been a particularly influential figure in the development of your music? Has that relationship affected your work?

Every musician from St. Louis to Botswana has been influenced by him. Why would it be any different for me?

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

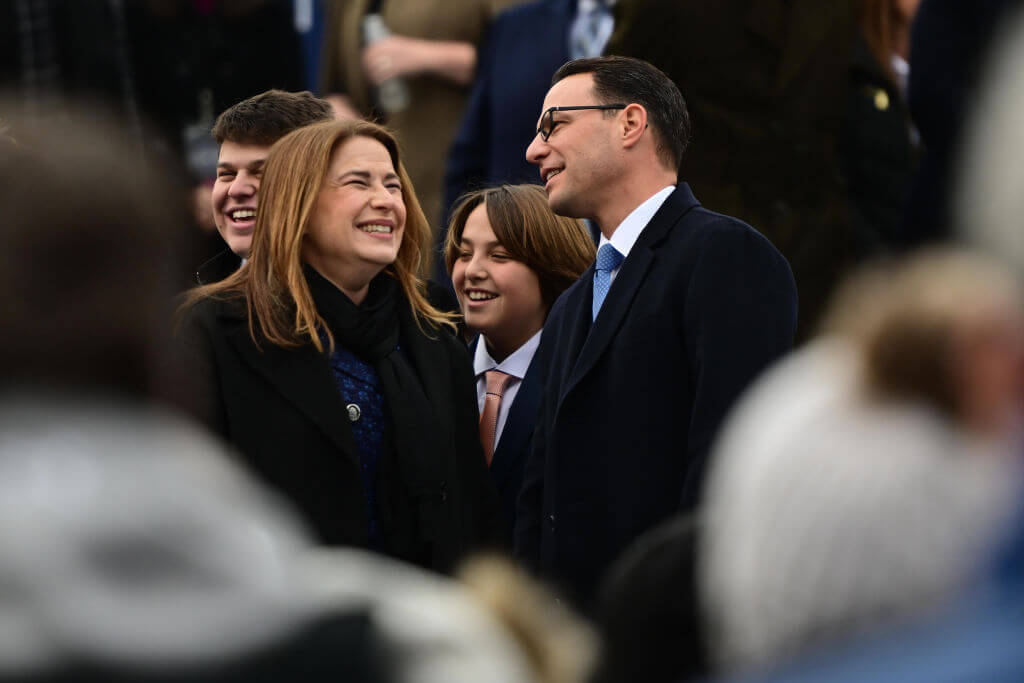

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Shapiro house fire suspect targeted Jewish governor over pro-Israel stances, search warrant says

-

Fast Forward Jewish family killed in New York plane crash

-

Fast Forward Israelis can no longer enter the Maldives after Palestinian-solidarity ban goes into effect

-

News Harvard is defying the Trump administration — after its own crackdown on academic freedom

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.