Histories Again Collide On the Hills of Jerusalem

Ancient View: The Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan (right) sits next to the Mount of Olives. Image by NATHAN JEFFAY

Silwan — known in biblical times as Shiloach — is a sprawling neighborhood a five-minute walk from the Western Wall at the southern entrance to the Kidron Valley. Today it is home to 55,000 Palestinians and 450 Jews who are concentrated in the section of the neighborhood closest to the Old City, Wadi Hilwah. Clashes between the two populations are common, but perhaps even more bitter than the physical violence is the narrative war taking place between them.

On the main street in Wadi Hilwah, less than 50 yards apart, are the entrance to the City of David, through which 500,000 visitors walked last year, and the Wadi Hilwah Information Center, an advocacy center run by local Palestinians. Each represents a claim to what is perhaps the most sacred historic basin on the planet, and their conflicting accounts highlight the greater tensions in Jerusalem today.

Dueling Narratives: Visitors begin a tour organized by Elad, a not-for-profit that seeks to emphasize the Jewish historical links to the disputed area. Image by NATHAN JEFFAY

The latest flashpoint occurred June 21, when Jerusalem’s Local Planning and Construction Committee approved a plan to demolish 22 illegally built Palestinian homes in Silwan. The objective is to make way for an archeological park and tourist center adjacent to the City of David that will be called the King’s Garden, a nod to the belief that the area was the garden of ancient Israelite kings. Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat strongly defends the plan, contending that it will bring development and order to a long-neglected part of the city. In an interview with the Forward, he also stressed that “Ir David [the City of David] is not part of Silwan.”

But the plan is drawing critics from within Israel and without, both on substance and on timing. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said that the plan was “contrary to international law” and “unhelpful” to efforts to restart peace negotiations, the Obama administration said it “undermines trust” and even Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak questioned the timing of the announcement, saying that it “lacked common sense.”

On the basis of findings from the past decade, the City of David is widely believed to have been where King David first established Israelite Jerusalem. The City of David Foundation — a not-for-profit better known by its Hebrew name, Elad — stresses the ancient Jewish links to the area, and argues that by extension, Jewish residence today is desirable and Israel should not withdraw from there in any future peace deal. Excavations, though undertaken by the Israel Antiquities Authority, are heavily funded by Elad — an issue of contention among some Israeli archeologists.

Rafael Greenberg of Tel Aviv University wrote last year that Elad mixed “religious nationalism with theme-park tourism. As a result, conflict with local Palestinians occurs at the very basic level of existence, where the past is used to disenfranchise and displace people in the present. The volatile mix of history, religion and politics in the City of David/Silwan threatens any future reconciliation in Jerusalem.”

In the movie theater a few yards inside the tourist entrance to the City of David, there is no such worry. “Welcome to the place where it all began,” the narrator booms, before going on to tell visitors that the beginnings of Israelite Jerusalem are not inside the Old City walls but rather there, where archeological findings suggest that David established his kingship, and where they can see newly uncovered sites mentioned in the Bible. The Jews living there today are portrayed as reviving that original Jerusalem.

That version of history is contested at the Wadi Hilwah Information Center. According to pamphlets at the center, “findings that prove unequivocally the existence of King David and his city remain to be found.” They accuse Elad of editing out of the site the history of other cultures. Guides “focus almost exclusively on King David and the Jewish periods,” and signage “tells the Jewish narrative of Jerusalem while neglecting the stories of many other cultures whose part in the city is no less important than the Jewish one.”

Center director Jawad Siyam claims that Elad is manipulating archeology to make a political argument for Jewish control of East Jerusalem. “What Elad is trying to do by controlling the archeological site is to make a Jewish agenda and trying to destroy the history of others,” he said.

But at the City of David, this accusation is dismissed. Eli Alony, a recent immigrant from New York and the organization’s director of strategic development, said that Elad simply presents archeological finds to the public, along with a narrative based on those finds. Artifacts relevant to Islamic history would be displayed if found, but they are rare, as the area was uninhabited through much of the Islamic presence in Jerusalem. He argued that the only reason Palestinians object to Elad’s presentation of the finds and the conclusion it draws from them is that the clash with their own narrative. “The ground speaks for itself,” he said, arguing that findings vindicate claims of the Jewish connection to Jerusalem and “prove the authenticity of the Bible.”

He said: “What you have today is a problem to Islam: In recent years, you have an attempt to rewrite history, saying that Jews were never in Jerusalem and that the Temple never existed. This worked for a while, but then there were these finds saying that Jews were here 3,000 years ago.”

Siyam insists that Palestinians have no desire to deny Jewish history, but he sees the running of an archeological site and funding of excavations by an ideological body as unacceptable. “There is no place in the world where an organization with a political agenda like Elad could control an archeological site,” he said, calling for the government to assume direct authority.

Siyam also criticizes Elad’s role in bringing Jewish residents to Wadi Hilwah, claiming that Elad has a “transfer agenda” in that it wishes to see Palestinians leave Wadi Hilwah. “Elad is using all methods in order to make a Jewish majority in Wadi Hilwah,” he claimed, questioning the morality of some of the methods used to acquire properties, including the Absentee Property Law, according to which Israel can seize the property of Arabs who fled to enemy countries after the 1948 and 1967 wars.

But Elad is insistent that all properties it has helped Jews to inhabit were ethically acquired, and Alony said the organization believes that “Muslims, Christians and Jews have the right to live where they wish in Jerusalem.” He claimed that Elad is actually righting an ethical wrong in some cases, as some of the properties acquired under the Absentee Property Law were actually Jewish-owned before Jordan took control of the area in 1948.

“We want to show that we firmly believe in the democratic process,” Alony said. “This is not a right-wing settler organization that believes that Jews and only Jews should be living in Jerusalem. That’s a smoke block that clouds the beauty of the results of our archeological finds.”

Contact Nathan Jeffay at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Arson suspect attacked Shapiro over pro-Israel stances, search warrant says

-

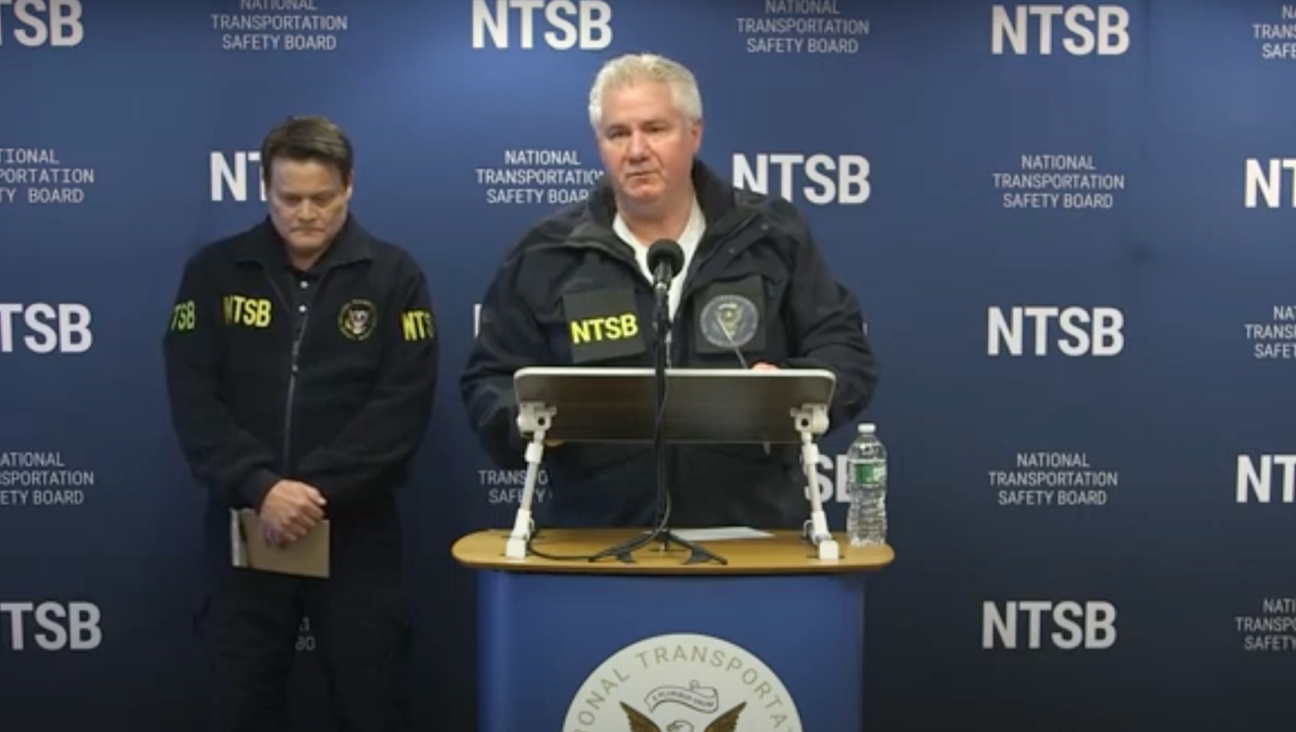

Fast Forward Jewish family killed in New York plane crash

-

Fast Forward Israelis can no longer enter the Maldives after Palestinian-solidarity ban goes into effect

-

News Harvard is defying the Trump administration — after its own crackdown on academic freedom

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.