For Reform Judaism, Change Is the Constant

Two hundred years ago, in the small Westphalian town of Seesen, the latter-day court Jew Israel Jacobson built a small synagogue intended mainly for the impoverished boys in the vocational school he had founded there. What made the “Jacobstempel,” as it became known, unusual was that it contained an organ; the bimah was at the front of the sanctuary, rather than in the traditional center; and, along with edifying sermons from the pulpit, vernacular hymns were sung during services conducted in an atmosphere of worshipful decorum.

Jacobson was not a conscious “reformer” of Judaism; he merely wanted to bring its externals up to date. Yet the July 1810 dedication ceremony of that temple is now being celebrated as Reform Judaism’s starting point. Reform Jews around the world are referring to this year as their movement’s bicentennial.

Some might see a certain irony at work here. In recent years, after all, the Reform movement has become ever more traditional in its worship style, reversing some of the reforms advanced by its founders and extended by proponents of so-called Classical Reform. So how can the Reform movement claim the establishment of the Seesen temple as its genesis moment even as it backs away from some of Jacobson’s innovations?

Perhaps we can find an answer to this question by examining a second significant bicentennial that Reform Jews have reason to celebrate this year: the 200th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Geiger, the rabbi and scholar from Frankfurt who gave intellectual substance to Jewish religious reform a generation after Jacobson.

A brilliant scholar of Judaism in the new critical vein known as Wissenschaft des Judentums (the scientific study of Judaism), Geiger anchored Judaism firmly within history. Judaism, he argued, had developed from stage to historical stage: Rabbinic Judaism differed from biblical, medieval from rabbinic. Each new phase represented religious and moral progress, each an adjustment to the changing conditions of Jewish life.

Based on this historical understanding of Judaism, Geiger could argue that adaptation in the past justified adaptation in the present. Religious reform was not an aberration but tied to the main line of Judaism’s religious history.

Although his basic conceptions lent themselves to radical implications, Geiger was himself an observant Jew whose prayer book retained traditional elements such as resurrection of the dead and whose congregants sat in synagogue separated by gender. His “Liberal Judaism,” an approach somewhere between American Reform and Conservative Judaism, became dominant in a German Jewry that sought to maintain maximal communal unity.

It was primarily in America, toward the end of the 19th century, that Reform Judaism took on the radical character that we today call Classical Reform. It drew on both the aesthetic sensibilities that received early expression in the Seesen temple and the ideology of Abraham Geiger and other German rabbis.

Classical Reform attracted German-Jewish immigrants who sought a universalistic faith even as, socially, discrimination kept them apart from non-Jews. America was their Zion. They believed that excessive ritual was likely to detract from a proper expression of a Judaism that consisted of prayers, almost entirely in the English language, and sermons — generally half an hour or more in duration — intended to teach and edify. Their reason for remaining Jewish had nothing to do with ethnic identity, but rather with a “mission” to propagate an ethical monotheism that, religiously and morally, stood prior to and above all other faiths.

By the 1930s, with the influx of a bit of Eastern European yiddishkeit and a darkening situation for Jews in Europe, Reform Judaism started to reverse course. By 1937 the movement had officially endorsed Zionism, and shortly thereafter it began gravitating toward increasing traditionalization of the Reform prayer book and of the ambience of the Reform synagogue.

Today, even as these trends continue, a reevaluation of the Classical heritage has begun to take place. In a recent sermon, the Union for Reform Judaism’s president, Rabbi Eric Yoffie — himself a proponent of the turn toward greater emphasis on Jewish tradition — called favorable attention to the early reformers’ intellectual rigor, universalistic ethics, compelling sermons and majestic music.

But for the most part, Reform Judaism, 200 years after its symbolic origins, is a quite different entity. In some respects it has become more radical than its earlier historical manifestations, with its complete religious equality for women and gay, lesbian and transgender Jews; its full-throated embrace of patrilineal descent; and its greater willingness to include within the Reform community non-Jews who are committed to raising their children as Jews. Yet in most respects it is far more traditional than in its Classical days.

What, then, is the scarlet thread that binds Classical and contemporary Reform Judaism together? One can glimpse it in Geiger’s principle that Judaism is a historical entity, that change is endemic to its character and essential for its survival. Sometimes that change has been in the direction of tradition and sometimes toward novelty. Seen in retrospect, Reform has always been a matter of harmonizing Torah with contemporary life. Over the course of two centuries, all that have changed are the points along the spectrum between tradition and modernity where that harmonization takes place.

Michael A. Meyer is the Adolph S. Ochs Professor of Jewish History Emeritus at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati. He is the author of “Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism” (Oxford University Press, 1988).

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

- 2

Opinion Trump’s Israel tariffs are a BDS dream come true — can Netanyahu make him rethink them?

- 3

Fast Forward Cory Booker’s rabbi has notes on Booker’s 25-hour speech

- 4

News Rabbis revolt over LGBTQ+ club, exposing fight over queer acceptance at Yeshiva University

In Case You Missed It

-

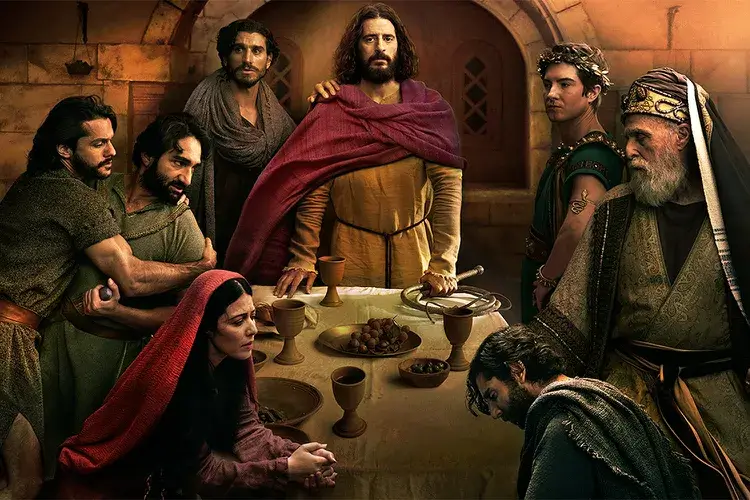

Culture The only good Jews in this hit Christian TV show are the ones who follow Jesus?

-

Books The golden age for American Jews is over — and wow was it short

-

Fast Forward AIPAC attacks Democrats who voted to stop arms sales to Israel

-

News How your matzah gets made: A peek inside the Streit’s factory

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.