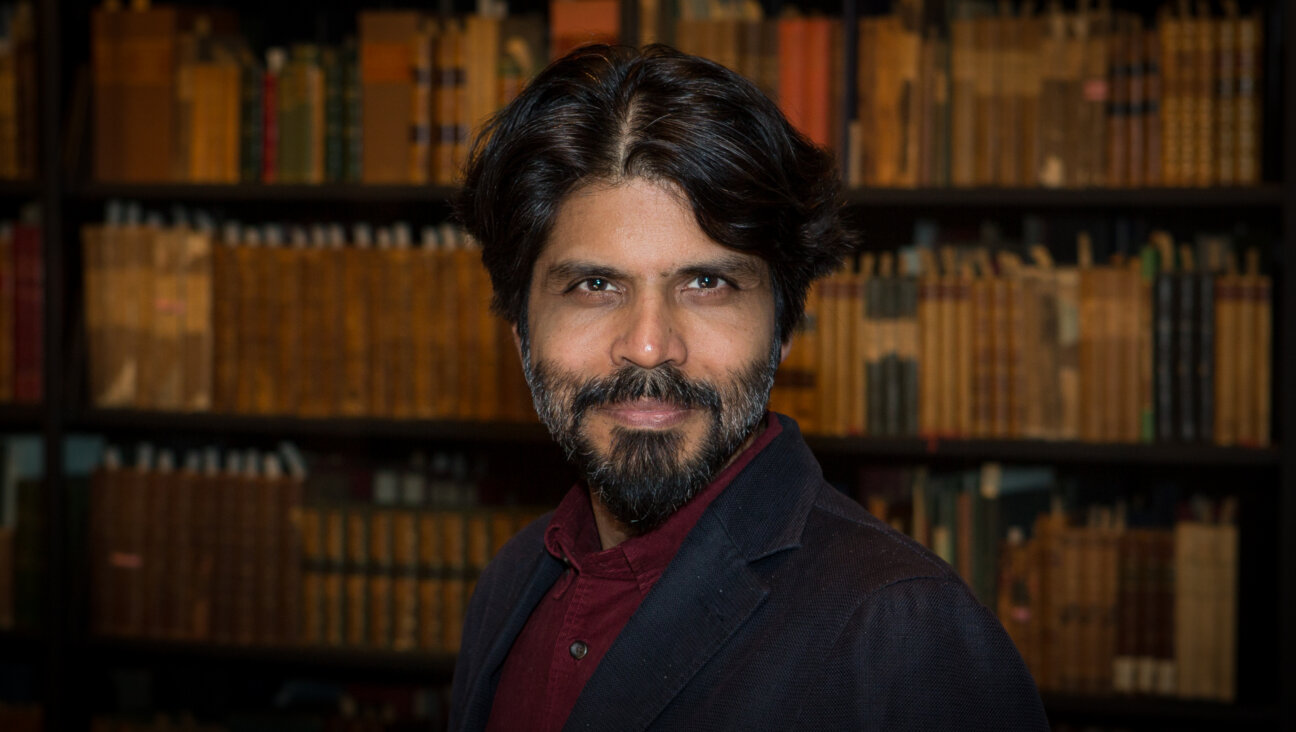

The Virtues of the Unaffiliated

It’s all about the unaffiliated. Ask anyone who runs a Jewish not-for-profit, and she’ll tell you: Success is measured in terms of how many “unaffiliated” Jews you get to “affiliate” — whether with Jewishness, Judaism or, at the very least, the latest program, trend or synagogue-outreach initiative. Organizations that don’t focus on the unaffiliated have a lot of trouble getting funded; those that do, even if they do so in highly debatable ways, often find generous supporters.

But what if the unaffiliated are right?

The usual narratives of The Unaffiliated Jews (that is, everyone except that minority of Jews who join synagogues or other institutions, from the merely apathetic to atheist children of mixed-faith couples, rebellious X-Os — ex-Orthodox — to parents who quit synagogue after their kids’ bar mitzvahs) run like this: They didn’t have the right education; they haven’t been shown an enthusiastic Judaism; they haven’t been to Israel. And as a result of these privations — unaffiliated Jews are defined by what they lack — they don’t join our clubs.

But many unaffiliated Jews are actually quite affiliated. Instead of merely associating with their Jewish community, they’ve joined cultural organizations, political organizations, professional organizations — not to mention other religious groups and, dare we admit it, the mainstream of American society. They’ve become Leonard Bernsteins and Lisa Loebs, Michael Bloombergs and Barbara Boxers. They are cosmopolitan Jews, outward facing, caring less about the tribe than about the wider world.

And maybe they’re right.

Of course, many unaffiliated Jews simply haven’t been exposed to what Judaism has to offer, except perhaps for the most risible of clichés and ossified rituals and dogmas. But let’s consider those who have — and have simply chosen otherwise. Isn’t it fair to question whether a strong sense of “identity,” particularly one connected with religion and ethnicity, is such a good idea in the multicultural 21st century? Is the best way for us all to get along really for each of us to take special pride in an aspect of the self that separates and differentiates? Sure, in the best-case scenarios, it’s possible to rejoice in one’s own ethnicity/religion/nation/peoplehood while not denigrating others; this is the idea of the “gorgeous mosaic” as opposed to the melting pot. But more often, any line that divides begins to conquer.

Now, as with Jewish anti-nationalists who just so happen to focus on one of the most vulnerable nations on the planet, one certainly could argue that while identity should be cast aside, or at least diluted, let’s not start with the embattled, disappearing Jews. Fair point. But one also could argue, as professors Jonathan and Daniel Boyarin have, that Jews are uniquely situated to construct a post-“identity” identity, because we’ve been doing so for the past 300 years. Jews have arguably created post-national identity, post-ethnic identity and post-religious identity. We even, at our mystical best, create a post-personal identity, as well, as the ani (I) merges with the ayin (Divine emptiness). So, if not us, whom?

Second, isn’t it often the case that by building a sense of “Jewish identity,” we turn our backs on some of the personal and social richness of being a cosmopolitan, 21st-century, net-surfing, iPod-mixing postmodern citizen of the world? When we choose familiarity over quality, aren’t we often settling for mediocre parochialism? Sure, the real, crazy, boundaryless world is de-centering, dizzying and sometimes bewildering. But it’s also exhilarating. I love hearing Senegalese music, Amerasian poetry, and talk of post-colonial politics — preferably all at the same time. And while I also love contributing my queer, Jewish, Buddhist, law-professor-kabbalist-poet flavors into that mix, I don’t want to shut out other ingredients in order to put mine in. In today’s world, sometimes affiliating carries its own costs.

Third, maybe the unaffiliated are seeing through our community’s well-financed publicity games, and seeing that there’s no there there. Jewish organizations are now tripping over themselves to repackage, market, dilute and otherwise sanitize Judaism for mass consumption. There are, of course, many others who are serious about meaningful learning, engaged community, personal transformation, social justice and spiritual growth. But because each of these is a niche play, all of them tend to lose out to Jewish Wal-Marts, which sacrifice depth for breadth — or, worse yet, Jewish cheerleaders whose hoorays for our tribe/state/religion/social class fall on increasingly deaf ears. Maybe if we gave our unaffiliated audience a little more credit, we’d look a little less desperate, a little less eager to hawk our latest wares. But we don’t do that, usually; we’re told that the best way to sell Judaism is the way we sell dishwashers: Keep it Simple, Stupid. Well, maybe the unaffiliated are too smart for us.

But most of all, what I like about the word “unaffiliated,” even though I have no right to claim it for myself, is how it suggests a certain kind of nonstickiness — a lightness, perhaps, that befits both our cultural moment and the spiritual virtues of openness, surrender and compassion. On such a path, identities, Jewish and otherwise, are as much obstacle as aid. Unaffiliated-ness, on the other hand, is nimble. As a semiprofessional Jew, I understand that nimbleness does not a continuous community make; I have seen the numbers, and I get it. But in my own heart, I’m ambivalent about the implications of being “affiliated.” Connected, yes; nourished, often; not to mention inspired, provoked, informed and reminded. But if I had to choose, I think I affiliate more with the unaffiliated.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 3

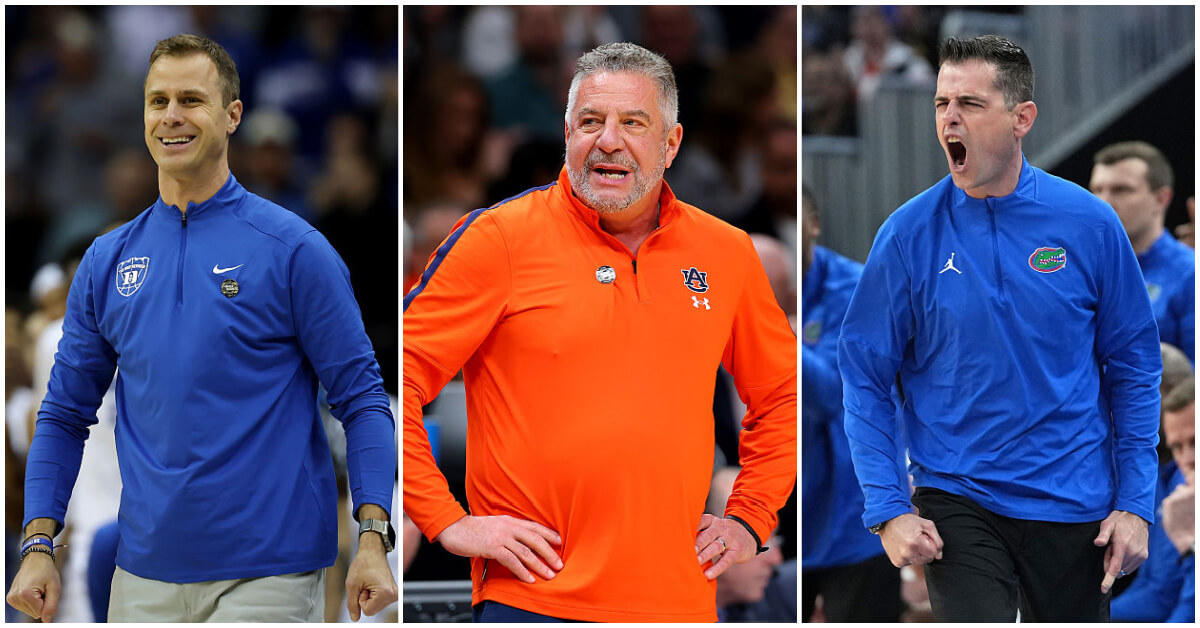

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Marine Le Pen may be headed to prison — antisemitism and xenophobia still roam freely

-

Fast Forward Israel announces new offensive to seize ‘broad territories’ of Gaza Strip

-

Film & TV Val Kilmer was the voice of my generation’s Moses (and God)

-

Fast Forward Cory Booker spoke at a synagogue on Yom Kippur. Its rabbi says Jews should learn from his 25-hour Senate speech.

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.