Obama Administration Presses Palestinians To Enter Direct Talks With Israel

From The Top: Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas received a letter from President Obma, encouraging direct talks. Image by GETTy IMAGES

State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley strove hard to hit the right note August 2 in describing the Obama administration’s recent effort to push the Palestinians into direct peace talks with Israel.

“There are consequences to failing to take advantage of this opportunity,” Crowley said of the Palestinians’ reluctance to enter direct talks, as reporters peppered him with questions regarding what was widely seen as American pressure on Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas. But then he quickly added that his statement was “not a threat,” making clear that the United States is “not picking a fight with anybody.”

Behind the laundered language used by American officials to describe the state of relations with the Palestinian Authority stands an American attempt to tread a thin line. On the one hand, the administration, according to both its public statements and the private messages that it relayed to the parties, believes that it is critical to enter direct talks before Israel’s settlement freeze expires in late September. On the other hand, the administration wishes to avoid being seen as pushing Abbas beyond his political comfort level, thus potentially losing its key ally on the Palestinian side.

But as the Middle East peace process takes on a new theme, one in which Israel is praised for its forthcoming approach and the Palestinians are seen as obstructing the administration’s goal of launching direct negotiations, it is clear that the heat is now on Abbas.

On July 16, President Obama sent Abbas a letter urging him to enter direct talks with Israel and making clear that if the Palestinians wish to see progress toward achieving a two-state solution, direct talks are the only way.

The White House did not make the content of the letter public, but administration officials disputed accounts in the Arab media claiming the letter threatened that American-Palestinian relations would take a hit if the leadership in Ramallah does not give its consent to direct talks.

“It is flat-out wrong,” said a State Department official who asked not to be named.

“We are having an open and frank exchange with the Americans,” Maen Areikat, head of the Palestine Liberation Organization delegation in Washington, told the Forward “It never reached the point in which pressure was exerted.”

According to Areikat, differences with the Obama administration focus on the Palestinian demand to set clear terms of reference and timelines for direct talks, and to ensure that Israel does not expand settlements while negotiations take place.

But although the United States declined to use the term “pressure,” Palestinian officials and Israeli diplomatic sources briefed on talks with the P.A. said the administration had a clear message. Abbas and his negotiators were told by Obama and by Middle East special envoy George Mitchell that direct talks are the only game in town and that any expectation for Israeli concessions could be realized only after entering talks.

In comparison with the treatment that Israel’s government received when it refused to accept America’s demands, the pressure on Abbas seems minor. Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, had to endure a cold shoulder in Washington and public scolding from top administration officials after deciding to build in East Jerusalem. For Abbas, also known as Abu Mazen, harsh language, if any, was kept away from the public eye.

But experts argue that this comparison is not valid. For the Palestinians, some say, even the slightest hint of displeasure from Washington could be devastating. “Abu Mazen is in an extraordinarily weak position,” said Philip Wilcox, a former American diplomat who negotiated with Palestinians. “He has nowhere else to turn.” Wilcox, who heads the Foundation for Middle East Peace, a Washington think tank devoted to promoting a two-state solution, added that Abbas’s main asset is that he has ties with the

United States, and so he cannot afford to resist the administration’s demands.

“The administration has more leverage with the Palestinians than with any other group of people in the world,” added Hussein Ibish, senior fellow at the American Task Force on Palestine. According to Ibish, the Palestinians’ only card is the administration’s belief that solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is in America’s national interest. Abbas, he said, would ultimately compromise, if for no other reason than a fear of the United States losing interest in the issue. “The Palestinians didn’t get all they wanted, so they’re whining a bit now, but at the end of the day, they will agree,” Ibish predicted.

When dealing with Israel, the administration chose to use open criticism, hoping — futiley, it turned out — that it could bypass the leaders and reach the Israeli people. But when it came time to pressure Palestinians, the United States preferred using friends and allies to deliver its message. The administration held quiet talks with European leaders and with moderate members of the Arab League, urging them to tell the Palestinians that there would be no compromise on the demand for direct talks. These talks eventually resulted in an Arab League resolution allowing Abbas to decide whether to enter direct talks, a step viewed by the Obama administration as a strong signal to the Palestinian leader that it was time to say yes.

Convincing the Palestinians to join talks also entailed offering them incentives, according to sources close to talks sources close to talks between the U.S. and the Palestinian Authority. These included openness to discussing Palestinian demands for setting terms of reference once an agreement to attend negotiations is delivered.

On the symbolic side, the administration agreed to allow the PLO mission in Washington to fly a Palestinian flag, an act that previously had been forbidden. Areikat said the gesture had nothing to do with the expectation of the United States that Palestinians enter direct talks.

The flag, however, has not yet been raised over the PLO mission’s office in Washington’s Dupont Circle. It took 16 years to receive the State Department’s permission to raise the flag, but now the Palestinians are waiting for permits from the building’s management.

Contact Nathan Guttman at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Make a Passover Gift Today!

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion What Jewish university presidents say: Trump is exploiting campus antisemitism, not fighting it

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Harvard president: As a Jew, ‘I know very well’ that concerns about antisemitism are valid

-

Fast Forward Ben Shapiro, Emily Damari among torch lighters for Israel’s Independence Day ceremony

-

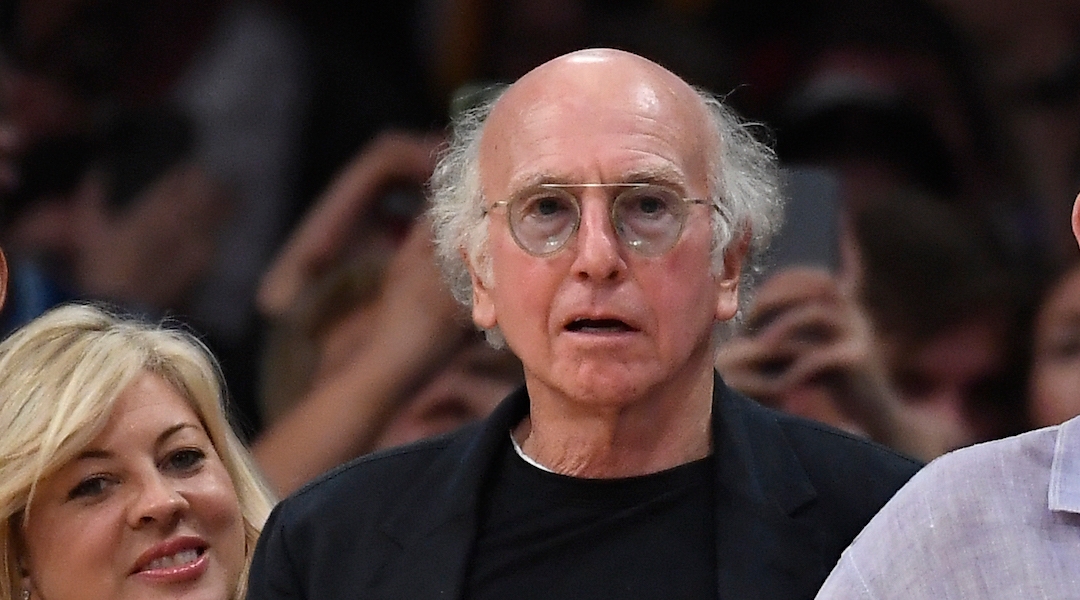

Fast Forward Larry David’s ‘My Dinner with Adolf’ essay skewers Bill Maher’s meeting with Trump

-

Sports Israeli mom ‘made it easy’ for new NHL player to make history

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.