Bluffing the Bolshoi

Old Comrades: In ?The Concert,? once-great Russian musicians get a last shot at glory. Image by CouRTESY of WILd BunCH

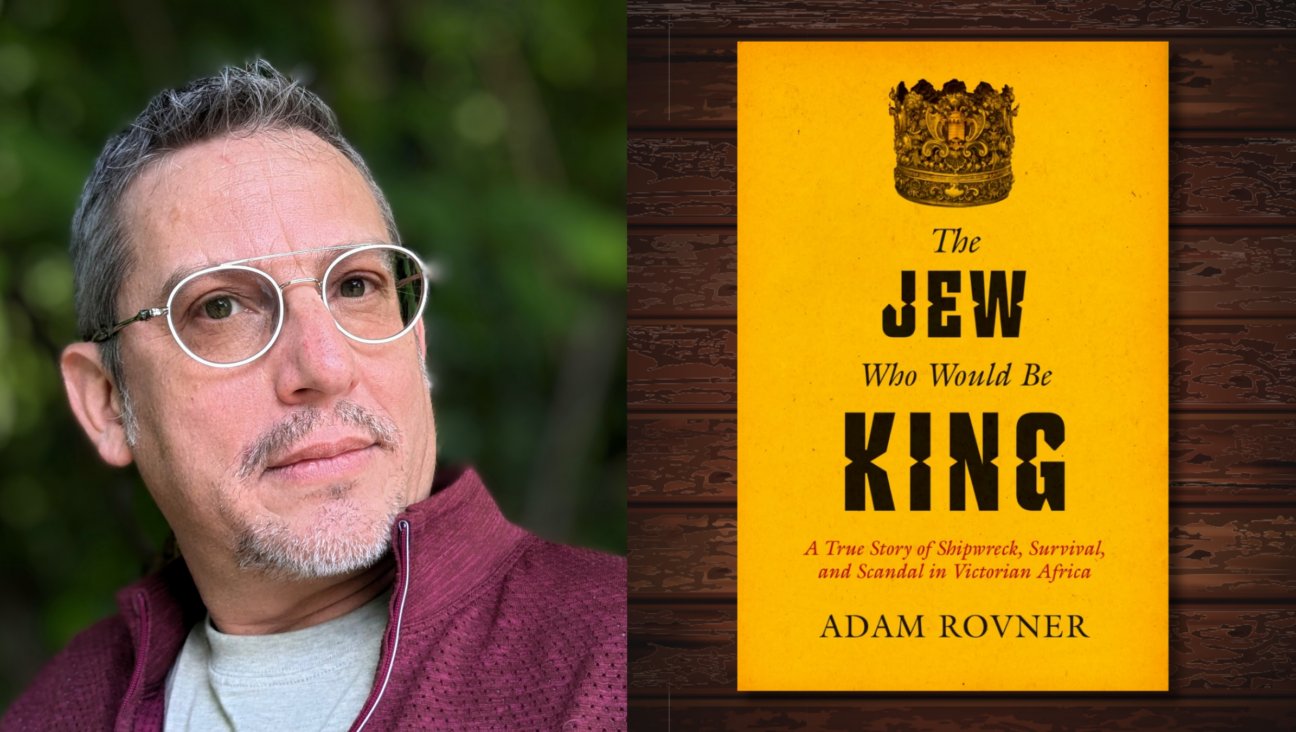

At the beginning of Radu Mihaileanu’s mischievous new comedy film, “The Concert,” we meet an observant Jewish trumpet player in Moscow named Viktor and his son, Moshe, who seems to have no connection to Yiddishkeit. At the end of the movie, Viktor’s yarmulke has been replaced by a cowboy hat, while Moshe has peyes and is dressed in full Hasidic garb. In Mihaileanu’s cinematic storytelling, characters always struggle to escape, survive or forge a new identity.

“I don’t have any more hate for the communists,” Mihaileanu said in a telephone interview from Paris, where he lives. “My revenge was shooting a comedy in Red Square, because maybe all the tragedies I lived and all the tragedies people around me lived came from there.”

Old Comrades: In ?The Concert,? once-great Russian musicians get a last shot at glory. Image by CouRTESY of WILd BunCH

Mihaileanu’s “tragedies” include his 1980 escape from Romania and the communist Ceausescu regime. His father, a Jew born Mordechai Buchman, was also something of an escape artist. Buchman fled a Nazi labor camp and emerged as Ion Mihaileanu with the help of fake identity papers. A communist under the Nazis, he became an anticommunist under the communists.

Radu Mihaileanu, now 52, seems to have inherited these “outsider” genes. After leaving Romania for a brief visit with his grandfather in Israel, Mihaileanu moved to France, where he had to start his career from scratch. As a Jew he was an outsider in Romania, and as an immigrant he was an outsider in France.

So, it’s no big surprise that outsiders populate his films. In “Train of Life” we meet a village of them during the Holocaust, and they try to escape the Nazis by building a train and disguising themselves as guards and prisoners who are being deported. In “Live and Become,” Mihaileanu introduced us to an Ethiopian boy who passes for being Jewish in order to be saved by Operation Moses. And now, in “The Concert,” we are presented with a Russian janitor who hijacks an invitation for the Bolshoi Orchestra to perform in Paris. It’s the latest in Mihaileanu’s tales of people who deceive for a higher purpose.

The janitor who masquerades as the conductor of the Bolshoi Orchestra was at one time its actual conductor. He had been fired 30 years earlier, for refusing to discharge the Bolshoi’s Jewish musicians. Here the higher purpose is to take revenge on the communists who sent conductor Andrei Filipov and his Jewish virtuosos packing. Although largely fictitious, there may be a kernel of reality in this tale. Mihaileanu claims that the idea for the film initially came from a real plot to bring a fake Bolshoi Orchestra to China in 2001. And he insists that Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev forced out the great Russian conductor Evgeny Svetlanov for refusing to rid the State Symphony Orchestra of Jewish musicians.

The dramatic tension in “The Concert” arises out of the unwillingness of the motley crew of Russian classical musicians to rehearse or cooperate once they get to Paris, where they are scheduled to play with beautiful soloist Anne-Marie Jacquet (Mélanie Laurent) at the renowned Théâtre du Châtelet. Filipov (Alexei Guskov) had rescued them from unglamorous day jobs as taxi drivers and flea market vendors so that they could do the hijacked gig in France. But rather than dedicate themselves to art once again, the once-great orchestra musicians are totally preoccupied with making money. So, their performance of Tchaikovsky’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra arrives — without rehearsal for a conductor who hasn’t conducted in 30 years, and with a renowned guest soloist who has never played Tchaikovsky.

“In a way they are losers, because their destiny was broken 30 years ago,” Mihaileanu says of the sacking by Communist Party officials. “But they are wonderful losers who have a wonderful energy from the past. Then they wake up and they become the gods they were 30 years ago. I don’t judge them, because they were broken so much.”

Another reason for Mihaileanu’s reluctance to judge them may be that he relates to their status as “wonderful barbarians coming from East to West. I consider myself a barbarian. I don’t have maybe all those wonderful behaviors from the people in the West. But maybe people in the West… managed to lose the vital energy, that Slavian soul and that crazy energy.”

Mihaileanu may have been lacking “wonderful behaviors” when he arrived in the West, but he surely brought with him a deep-seated desire to create, something that he shared with his father. Ion Mihaileanu wrote for a cultural newspaper in Romania called Contemporanul, but was frustrated that censorship by the Ceausescu regime prevented him from writing what he wanted. He urged his son to flee Romania before authorities imprisoned him for his theatrical work, which included directing an amateur theater group and acting with a Yiddish theater troupe in Bucharest.

Mihaileanu says that his father’s struggles — and his own — inspired the message of “The Concert.”

“People have to dream… because they try to be free,” he said. “The condition of a human being is, for sure, not kneeling. It’s always standing. That’s part of my life. I always dream to stand again, not to kneel.”

He is currently at work on his next feature film — a riff on Lysistrata, but in Arabic. The women in a tiny village go on strike and won’t make love to their husbands until the men fetch drinking water from the top of a mountain. Mihaileanu’s contrarian absurdities continue.

Jon Kalish is a Manhattan-based radio reporter and podcast producer.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 3

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

- 4

Fast Forward How Coke’s Passover recipe sparked an antisemitic conspiracy theory

In Case You Missed It

-

Film & TV In ‘The Rehearsal’ season 2, is Nathan Fielder serious?

-

Fast Forward Pro-Israel groups called for Mohsen Mahdawi’s deportation. He was arrested at a citizenship interview.

-

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

-

Opinion This Nazi-era story shows why Trump won’t fix a terrifying deportation mistake

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.