B’Sha’a Tovah!

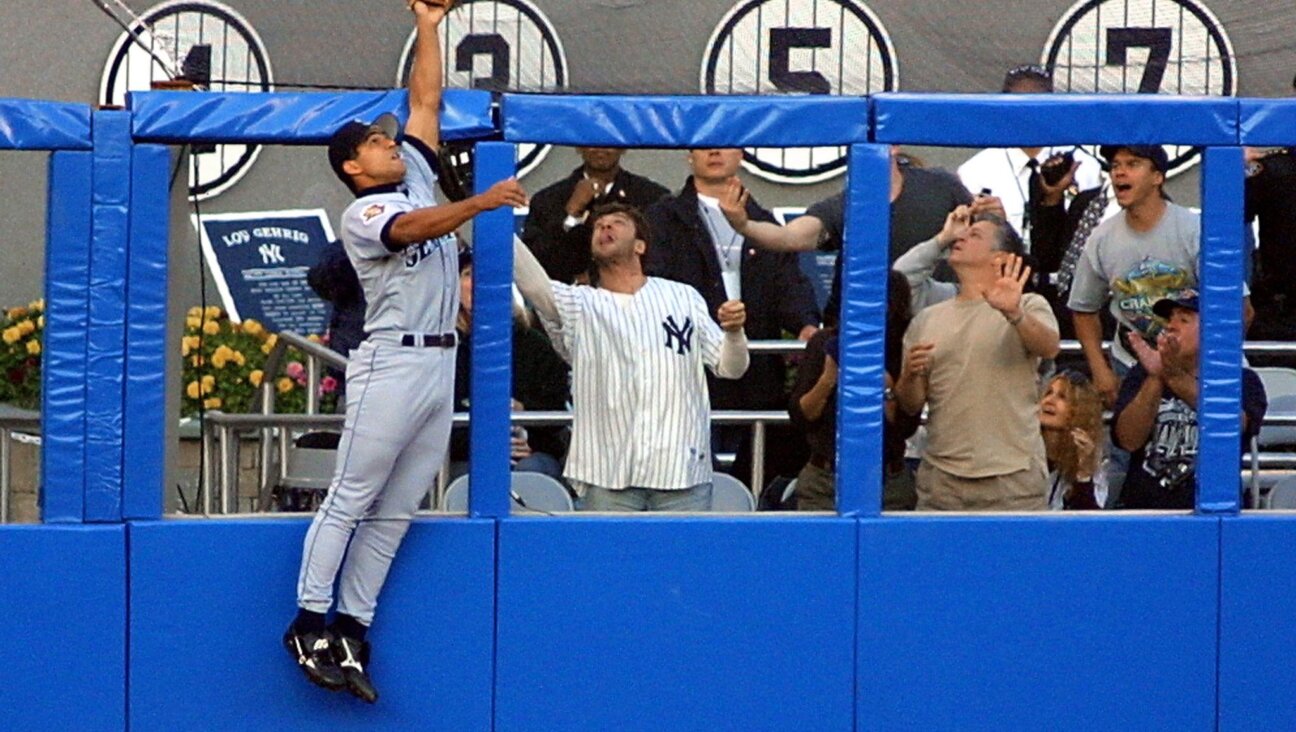

A blessed Event, in Potentia: The Metonic cycle has rolled around once more and the year is pregnant with a new month. Image by IsTOckpHOTO

Congratulations, we’re expecting!

That’s because the Jewish year 5771 that has just started is a “pregnant year,” a shana me’uberet in Hebrew. (Ubar in Hebrew is a fetus or embryo.) In other words, it’s a leap year, one in which the 12 regular months, six of 29 days and six of 30, “give birth” to a 13th to make up for the steady slippage — the “epact,” to use the technical term for it — of the Jewish lunar calendar vis-à-vis the solar one used throughout the world. In English, ibur ha-shana, literally, “the impregnation of the year,” is known as “intercalation.” This is a word that, surprisingly, has nothing to do with “calendar,” which derives from the Latin calendarium, an account book. Rather, it comes from Latin calare, “to proclaim,” since originally, leap years were not scheduled regularly but were periodically announced by public proclamation.

The solar year is 365 days and about six hours, and so needs an occasional leap year, too, an extra 24 hours every four years on the 29th of February. Our English expression “leap year,” however, is moon- rather than sun-born, since the “leap” in it comes from the medieval Latin term for adding days to the lunar calendar, saltus lunae, “a leap of the moon.” This is necessary because, since the monthly lunar cycle is about 29.5 days, a lunar year of 12 months has only 354 days. The result is an 11-day epact, so that, for example, whereas Rosh Hashanah fell this year on Thursday, September 9, it would arrive next year, if nothing were done about it, on Monday, August 29, which would, at the very least, disrupt our summer vacation.

To prevent this from happening, 5771 will be “pregnant” with another month. Adar, the sixth month of the Hebrew calendar, will now become Adar Bet, or Second Adar, and an additional 30 days called Adar Alef, or First Adar, will be inserted before it. Consequently, next year’s Rosh Hashanah will come 19 days — the 30 of Adar Alef, minus the 11 of the epact — later than this year’s, on September 28.

Jewish years are pregnant often — seven out of every 19. When the 19 years are over, we’ll be back where we started, with the lunar and solar dates lined up as they were at the outset, so that in the year 2030, the Jewish year 5790, Rosh Hashanah will again fall on Thursday, September 9. Called in Hebrew ḥokhmat ha-ibur, “the science of intercalation [literally, of impregnation],” this procedure for keeping the moon and sun in sync is better known as the Metonic cycle, after the fifth-century-BCE Greek astronomer Meton, who worked out its arithmetic in detail.

Meton didn’t hit on the Metonic cycle from scratch; he was preceded by the Babylonians, who were apparently the first to realize that 19 solar years, in which there are 6,939.75 days, are almost the equal of 19 lunar years when seven of these are given an extra 30-day month. And yet, almost is not exactly, because 19 such lunar years have only 6,936 days. How to make up for the remaining epact of 3.75 days? The Babylonians realized that the solution was simple: Add an occasional day to one of the 12 regular lunar months. In the Jewish calendar, which ultimately derives from the Metonic cycle, this means periodically turning a 29-day month into a 30-day one, a procedure known as ibur ha-ḥodesh, “the intercalation [or impregnation] of the month.”

We Jews thus have pregnant months as well as pregnant years. The month that gives birth to an extra day is always Heshvan, the second month of the year. Months and years, however, do not get pregnant together. Therefore, in 5769 and 5770, when the year was not pregnant, Heshvan had 30 days; in the year 5771, it will have only 29. The cycle of the 30-day Heshvan is complex, because, to ensure that Yom Kippur never falls on a Friday (in which case it would be impossible to prepare for the Sabbath), the month after Heshvan, Kislev, is sometimes shortened to 29 days from its usual 30, and things are determined by the interplay of the two.

It is the complexity of the Jewish calendar that led the rabbis to speak of sod ha-ibur, “the secret [knowledge] of intercalation,” as something so arcane that it had to be revealed to Moses at Sinai. And yet, as has been pointed out, the Greeks and Babylonians were the ones who first discovered it. Although even in biblical times, Jews must have added months to the year to keep their holidays from continually epacting and losing their seasonal associations (which is what happens in the lunar calendar of Islam, where intercalation is not practiced), they apparently did so on an ad hoc, unsystematized basis until the beginning of the Common Era. This was several hundred years after Meton, who, rather than Moses, laid the basis for our Jewish calendar.

Shana me’uberet tova 5771 to you all!

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]