Wanting To Connect, Israelis Find Religion

NEWCOMERS: Sarah Sela-Herman, a 47-year-old doctor from Israel, at her bat mitzvah in Los Angeles in January of this year.

Los Angeles – For Sarah Sela-Herman, an Israeli doctor, it took moving to Los Angeles from Haifa for her to finally undergo one of contemporary Jewish life’s most prominent rites of passage: a bat mitzvah.

NEWCOMERS: Sarah Sela-Herman, a 47-year-old doctor from Israel, at her bat mitzvah in Los Angeles in January of this year.

Sela-Herman, a 47-year-old pediatric gastroenterologist who celebrated her bat mitzvah in January, is among a growing group of Israelis who have moved to L.A. in recent years and found themselves far more involved in Jewish life and practice than they ever were in the Jewish state.

“I’m much more active in Jewish life here,” Sela-Herman said. “In Israel, either you’re Orthodox or you’re secular, but there’s not much in between.”

Los Angeles is home to one of the largest Israeli expatriate communities in the world. With an estimated 30,000 Israelis living in L.A., recent studies suggest that the city accounts for about one-third of the total number of Israelis who reside in America. While it has long been believed that Israeli immigrants do not affiliate with American Jewish institutions, including synagogues, anecdotal evidence indicates that at least in L.A., an increasing number of Sabras are becoming entrenched in American Jewish life.

According to Pini Herman, Sela-Herman’s husband and an L.A.-based Jewish demographer who performed the 1997 Los Angeles Jewish Population Survey, Israelis in L.A. are far more involved with Jewish life here than is widely perceived. “There’s a myth that Israelis don’t participate in the American Jewish community,” he said. “They’re actually overrepresented in participation.”

In L.A., Herman said, where an estimated 520,000 Jews live, one in every 40 people in the room at a Jewish communal event should be Israeli. “But if you look around at any communal event, you’ll find one in 10, or one in five — a much higher percentage.”

The differences between religious life in America and in Israel are stark. In America, synagogues across the denominational spectrum play a vital role in Jewish communal life. In Israel, however, synagogues — which are for the most part Orthodox, though branches of the Reform and Conservative movements there are growing — tend to be places where people go to pray, not places where average citizens go to drop off their kids at school or attend a lecture.

“In Israel, we don’t have the sense of community that synagogues have here,” explained Gilad Millo, L.A.’s Israeli consul for media and public affairs. “In Israel, synagogues are where people meet to pray on Fridays.”

Millo is a member of Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills, an 800-family Reform synagogue that claims about 50 Israeli family units. He also sends his two children to the synagogue’s day school.

In L.A., observers note, synagogues play a particularly central role in Jewish life, which could explain why some Israelis become more involved in communal life when they move here. Given the city’s sprawl, people tend to feel isolated. As a result — and in the absence of strong Jewish community centers that exist elsewhere in the country — synagogues offer an array of classes and groups in which people can participate. “It’s how you conquer the loneliness of L.A,” said Ed Feinstein, who is a senior rabbi at Valley Beth Shalom in the San Fernando Valley.

Within L.A., the Valley is home to the largest concentration of Israelis. That high concentration is reflected in the membership of Valley Beth Shalom, which is in Encino; about 10% of the synagogue’s membership is Israeli, according to Feinstein. He suggested that some Israelis living in L.A. have developed stronger connections to Jewish life as a response to the challenges of living in the diaspora.

“In Israel, Jewish life is largely unconscious,” Feinstein said in an e-mail. “That was the Zionist dream — make Jews and Judaism ‘normal.’ Normal means unconscious. Here, they discover that Jewish identity must be constructed and reinforced.”

Roy Zu-Arets, an Israeli composer and musician who moved to L.A. from New York almost three years ago, joined a synagogue for the first time in his life when he moved to Southern California. Zu-Arets, 39, joined Temple Emanuel — where he now performs at a monthly musical Sabbath service known as Shabbat B’Yachad — and enrolled his two children in the day school there. “It’s the first time I understand the meaning of being part of a community,” he said.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 3

Fast Forward How Coke’s Passover recipe sparked an antisemitic conspiracy theory

- 4

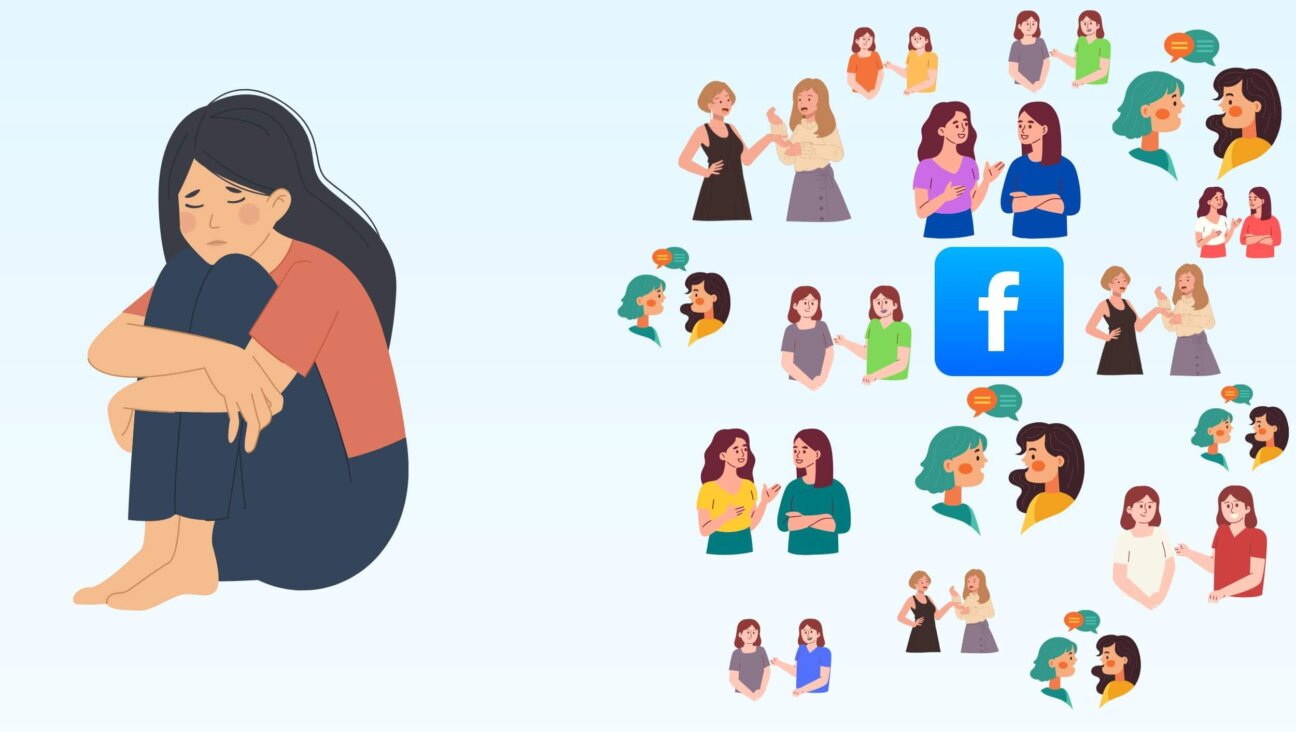

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion This Nazi-era story shows why Trump won’t fix a terrifying deportation mistake

-

Opinion I operate a small Judaica business. Trump’s tariffs are going to squelch Jewish innovation.

-

Fast Forward Language apps are putting Hebrew school in teens’ back pockets. But do they work?

-

Books How a Jewish boy from Canterbury became a Zulu chieftain

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.