Opening Minds on Campus

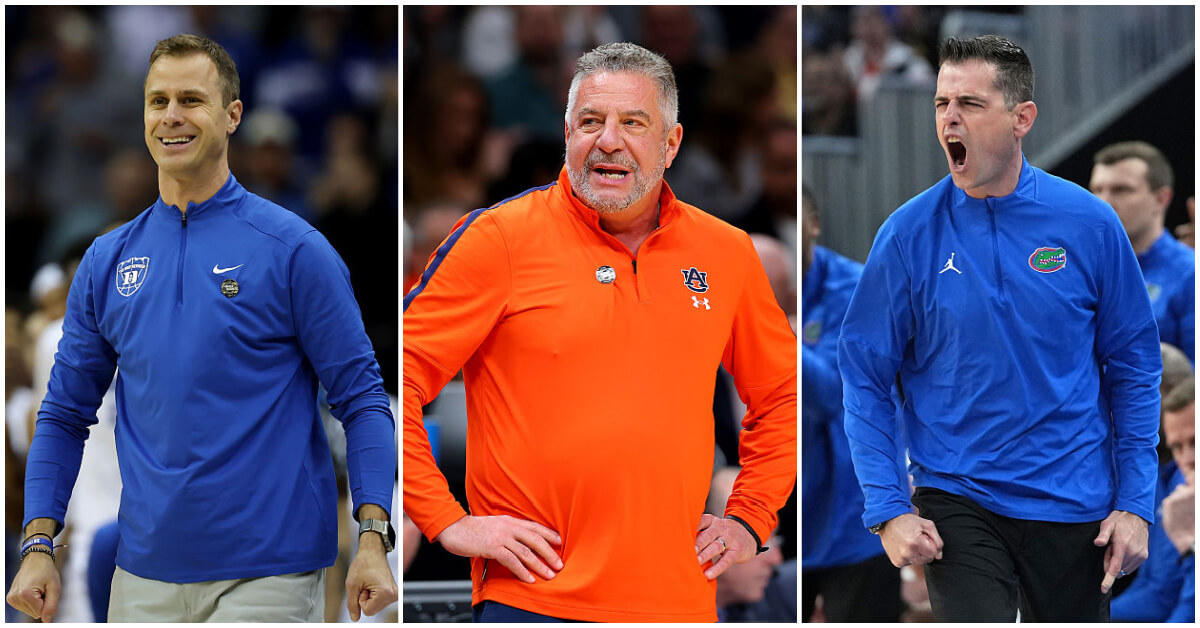

The Handbook: Duke freshman Imran Hafiz this summer promoted the Muslim teen guide he wrote with his sister and mother. Image by COURTESY DILARA HAFIz

We are a brother and sister of Pakistani descent who grew up in Arizona and are now enrolled at two of America’s finest universities. We are passionately interested in Jewish-Muslim dialogue because we believe the only way to decrease religious tensions is through engagement on a personal level. At college, we’ve found a lot of opportunity for such engagement — and a few challenges, as well.

The Handbook: Duke freshman Imran Hafiz this summer promoted the Muslim teen guide he wrote with his sister and mother. Image by COURTESY DILARA HAFIz

In Imran’s first week of college, he immediately had someone to hate. Or at least his dorm neighbor thought so. “Wait, Imran, why are you going to Shabbat this Friday?” he asked. “I thought Muslims hated Jews.”

As Imran quickly, sadly discovered, confusion about his involvement with the Freeman Center for Jewish Life at Duke University abounds — because he is an American Muslim. This reaction was just the latest example of how 9/11 drastically changed the experience of living as a Muslim in America for us, siblings raised by banker parents in suburban Phoenix.

Bullying, ignorant remarks from both teachers and students, nasty emails and an almost constant flow of negative media coverage on Islam shaped our development as adolescents.

We had hoped that college would bring a change. Ideally, college is a place for all students to challenge their conceptions of self and others. Yet once again we were encountering the damaging assumption that Muslims and Jews are inherently incompatible. While it is true that for many years, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has generated tension and mistrust between Muslims and Jews, we must remember that historically, these peoples have also supported each other, celebrating similarities such as an Abrahamic heritage and a focus on education and close family ties.

The larger problem is that we make generalizations about other people based on their religion, and while it is not appropriate for our friends to assume that we are anti-Semitic due to our religion, it is sadly understandable. Forward-thinking Jews and Muslims have not given the American public much to consider about how we feel about each other. It is time for that to change.

How do we take advantage of the unique opportunity that college provides to build a respectful dialogue of acceptance? Interfaith work needs to be more than feel-good rituals in order to effect the lasting social change necessary to build real understanding. At many college campuses, “solidarity” between different faith groups is encouraged and facilitated; for instance, in volunteer programs, young Muslims and Jews package food for the homeless or clean up parks together.

As worthy as these group efforts are, they can never be as successful as person-to-person engagement. Rather than letting others speak for us, even well-intended intermediaries, we should interact directly with each other.

At Yale University, flyers for Jewish lecturers are posted side-by-side with posters about Muslim speakers. Yasmine has happily lived with a Conservative Jewish roommate for the past two years, even attending the occasional Shabbat dinner. Her inbox is filled with emails from groups and clubs, including a weekly newsletter from JAM — Jews and Muslims at Yale. Discussions about religion abound on campus, and even issues such as Palestine/Israel are presented in an academic manner, as people usually attempt to avoid becoming mired in emotion, an approach which leads to a higher level of meaningful discourse.

Speaking up against injustice is crucial, regardless of what group is being maligned. J Street U, a national network of student activists committed to peace in the Middle East (associated with the larger J Street organization), started a petition in response to the Park51 controversy. Called “Stand Strong Against Islamophobia,” it states: “American Jews in particular are acutely aware of their own history of persecution as a religious minority, and our legacy commands us to fight for the rights of other religious minorities as resolutely and passionately as we fight for our own.”

We as Muslims should follow this brave demonstration of pluralism and find our united voice to stand shoulder to shoulder with other students of all faiths. We should not be afraid to open our hearts to the struggles of those who have preceded us.

September 11 was a painful, tragic, horrifying day. However, it made us realize that tragedies should unite us, not divide us. In order to protect our nation as a pluralist society, minorities in particular must reach out to each other, especially at university. How else can we hope to step out of our college gates into a more understanding world?

Imran and Yasmine Hafiz are the co-authors, with their mother Dilara, of “The Muslim American Teenager’s Handbook” (Atheneum, 2009).

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

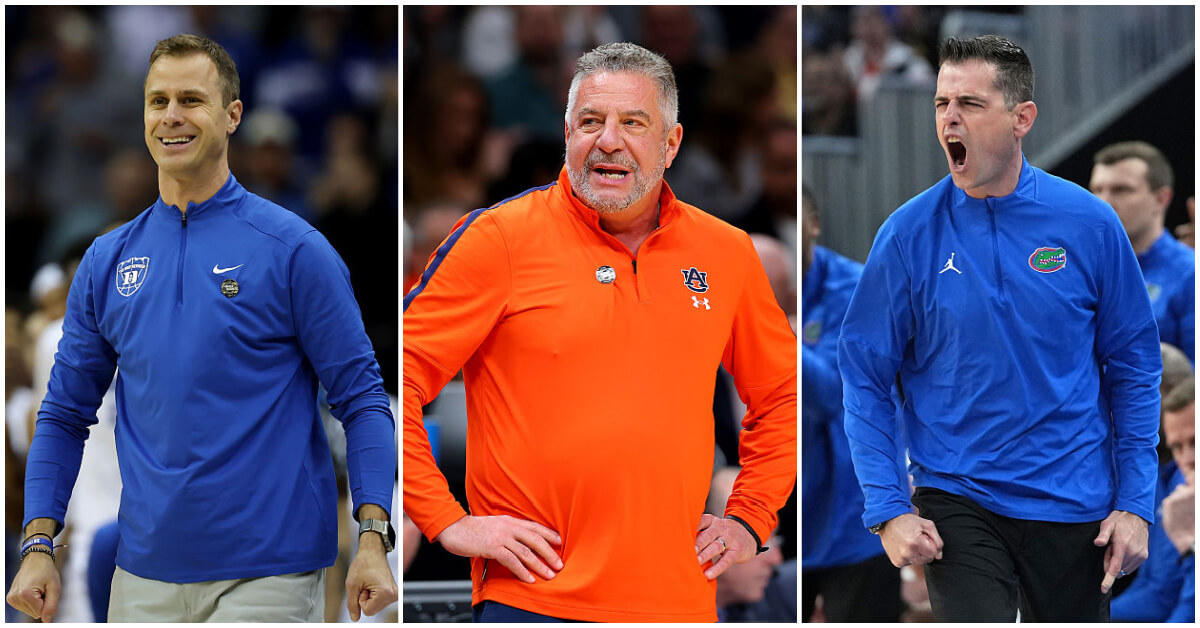

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.