True Drama

Wife and Prostitute: Jakob?s worlds collide when Ruth (Caitlin McDonough-Thayer to the left) and Nance (Mary Jane Gibson) meet. Image by luke Norby

Large theaters in 2010 seemed to mostly recycle earlier images of Jews, familiarly corrosive or sentimental (“Angels in America,” “Driving Miss Daisy,” “Collected Stories,” even “The Merchant of Venice”). It was left to smaller theaters to take fresh approaches to modern Jewish life and recent history. David Greenspan portrayed hilarious and hair-raising marital discord in his superb one-man show, “The Myopia,” from the Foundry Theatre; Deb Margolin made something fascinatingly eroticized and religious out of a front-page financial scandal in “Imagining Madoff” at StageWorks/Hudson; the resourceful Flux Theatre Ensemble re-imagined the Old Testament on a shoestring in “Jacob’s House”; in “Lingua Franca” at Brits Off-Broadway, gifted veteran playwright Peter Nichols conjured a sexy German émigré clinging to her anti-Semitism while teaching English in post-World War II Italy; and Vern Thiessen tackled infrequently dramatized Soviet prejudice in his effective black comedy, “Lenin’s Embalmers,” produced by Ensemble Studio Theater.

Closing the curtain on the year were two more productions with ambitions greater than their modest budgets and short runs.

“My Inner Sole,” which played five performances at the Lion Theater on West 42nd St. recently, was a stage piece by a Czech-born visual artist, Zuzka Kurtz. Her work has focused on the experiences of her parents, who survived Auschwitz and then fled the Soviets in Prague before settling in Israel. Her three-foot-tall skeletons dressed in luxurious clothes (with shoes culled from friends and family) express for her the omnipresence of death amid privilege that has shaped and haunted her life. For the theater, Kurtz expanded on the idea with music, dance, and monologues.

The most effective part of the evening was the most prosaic: searing anecdotes of death camp horror effectively related by actress Cynthia Adler (as Kurtz); and, in a brief appearance, Kathryn Grody as a voluble aunt made a persuasive argument for Kurtz getting on with life and getting some pleasure out it. “Memories,” she said, “are the lowest form of intelligence.”

The dance interludes, performed by Pepper Fajans and choreographer Wendy Osserman, contained occasional visual eloquence: Osserman tried to fight free of a sheer, blood-colored linen, as if she were Kurtz, emotionally hobbled by the cruelty her parents faced; Fajans became sensually intertwined with many of the eighteen skeletons on view, as if he were embracing decomposition.

Kurtz deserves credit for trying to portray the plight of the survivor’s child in a symbolic and non-traditional way, even if “My Inner Sole” was ultimately less a piece of theater than a private therapeutic effort, less an examination of an obsession with the Holocaust than a demonstration of it.

Characters are also hopelessly haunted by family misfortune in Tommy Smith’s “The Wife” (which ran at the 50-seat Access Theater downtown), though the committed wrongs were current, local, and sometimes self-inflicted. In this engagingly grim play, the need for connection among characters of different cultures was catalyzed by a crisis in the life of a young Hasidic couple.

Living in an unnamed New York neighborhood, Jakob (Noel Joseph Allain) and Ruth (Caitlin McDonough-Thayer) have lost their son “before he could be named.” Their grief propels them from their Haredi cocoon into the surrounding multi-cultural and hipster area from which they have been cloistered. Jakob begins a double life, rigidly religious on the surface, but engaging in sex with a boozy prostitute, Nance (Mary Jane Gibson), in private. Ruth secretly takes a job caring for the cat of an unstable graphic designer, also named Jake (Jacob H Knoll), in order to earn enough to leave the city and her husband.

Those they meet react to the couple’s formal and foreign-seeming wardrobe, attitudes, and accents with everything from fascination to fetishizing to mockery, revealing a desperate need to crack open their clannish insularity and grow close to them. The designer Jake develops a dangerously delusional crush on Ruth; Nance draws the wife into her underworld of drinking and drugs. As each relationship revolves and evolves into others, the two Jakes end up in disastrous collisions with Nance’s young daughter, Girly (Ayesha Ngaujah).

The idea of strangers from different cultures being connected by tragedy has recently become clichéd through earnest movies like “Crash” and “Babel”; and maybe there should be a year-long moratorium on using child death as a cathartic dramatic device (“Rabbit Hole,” “Mystic River”). Yet Smith’s play offered no hopeful Hollywood endings: in it, mourning caused bad decision-making, intimacy led to catastrophe, and people only get close enough to hurt and even kill each other.

While his structure sometimes seemed schematic and his imagery first draft-ish and unprocessed, “The Wife” also had a raw energy that was engrossing, along with a yearning and disgusted sincerity that haunted even after the surprisingly surreal and (only marginally) hopeful final scene.

The production was also exemplary. Director May Adrales cleverly scattered the action and audience to different areas, immersing us in new worlds as the Hasidic couple was immersed; and all the actors created fine, fully-dimensional portraits. In maybe the most difficult role, Allain managed to be both menacing and pitiable using only the limited amount of expressed emotion his character allowed himself. He served as a symbol for all the doomed attempts at union that dotted this admirably unsentimental play.

While well-funded theaters in New York feature the arrival of angels and interracial handclasps, low-budget venues continue to portray an ethnic and religious world harsher, more real, and truly contemporary. Maybe traveling light and flying under the radar are the real ways to reach a future in the theater.

Laurence Klavan is a playwright and novelist living in New York City. His graphic novels, “City of Spies” and “Brain Camp,” both co-written with Susan Kim, were published this year.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Make a Passover Gift Today!

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Opinion What Jewish university presidents say: Trump is exploiting campus antisemitism, not fighting it

- 4

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Harvard president: As a Jew, ‘I know very well’ that concerns about antisemitism are valid

-

Fast Forward Ben Shapiro, Emily Damari among torch lighters for Israel’s Independence Day ceremony

-

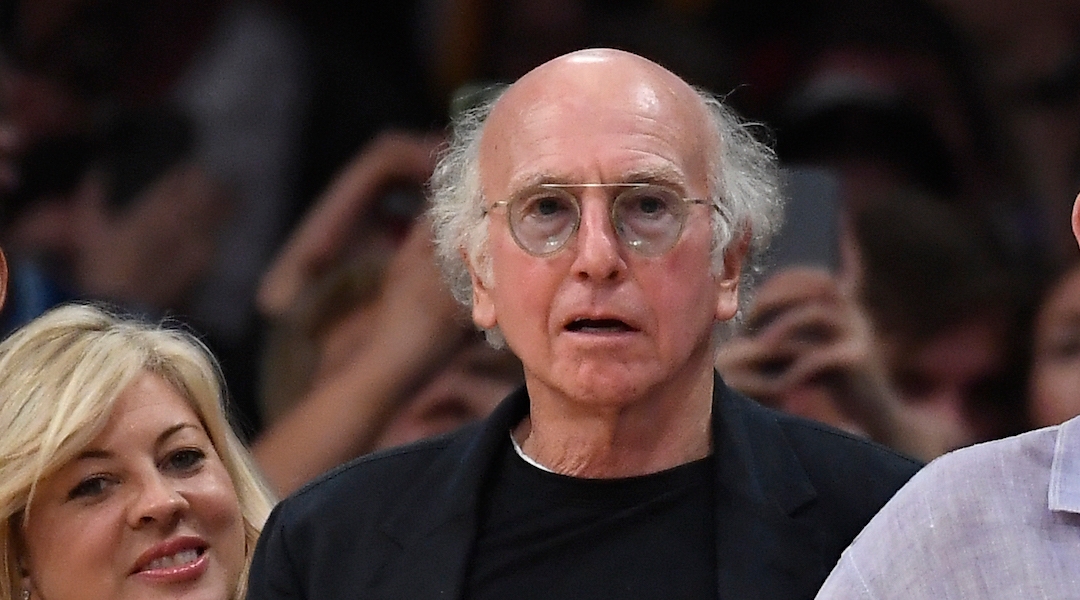

Fast Forward Larry David’s ‘My Dinner with Adolf’ essay skewers Bill Maher’s meeting with Trump

-

Sports Israeli mom ‘made it easy’ for new NHL player to make history

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.