Progress Seen in P.A. Crackdown On Incitement by West Bank Imams

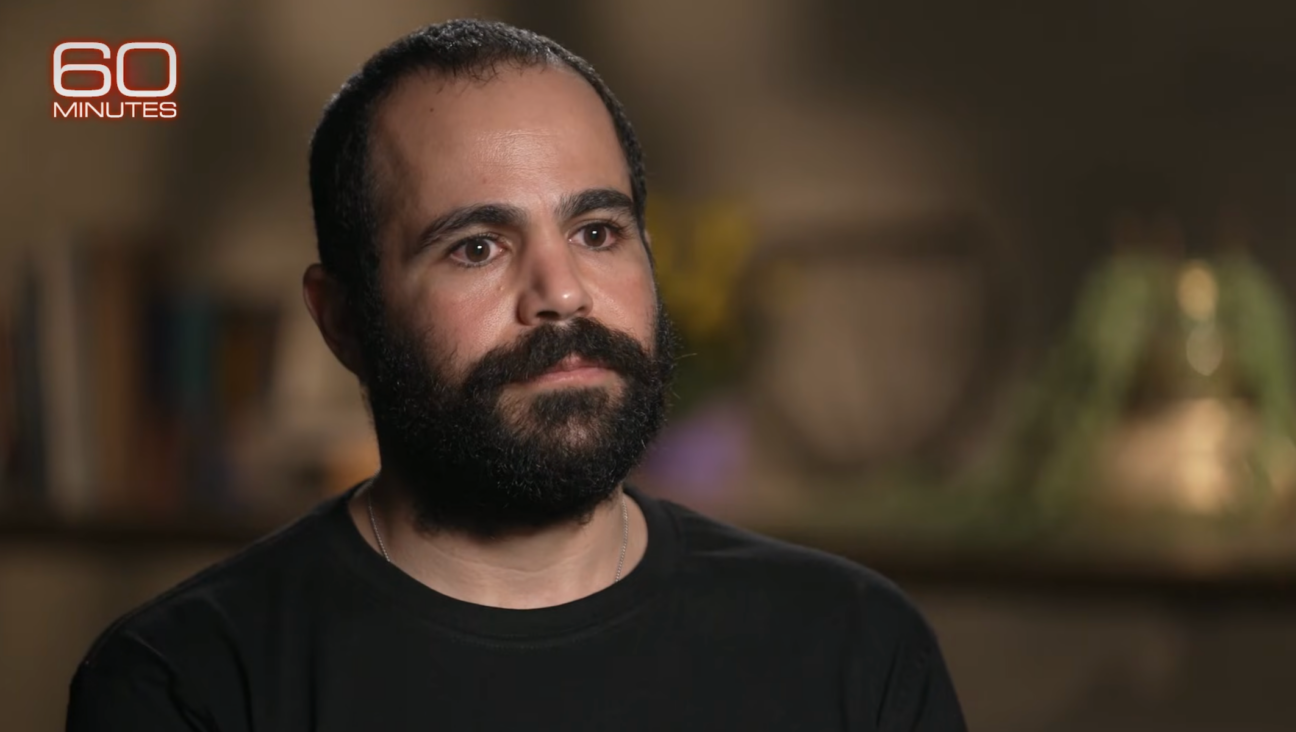

Abraham Foxman: ?It?s better than it was but still far from where it needs to be.? Image by Getty Images

With reporting from Nathan Jeffay in Israel and Nathan Guttman in Washington.

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process has seen its ups and downs, but one issue has remained constant: the crusade by Israel and American Jewish groups against incitement to violence. Israelis raise the issue time and again when negotiating with Palestinians, and American Jewry has adopted the struggle against incitement as a key item on its advocacy agenda.

Abraham Foxman: ?It?s better than it was but still far from where it needs to be.? Image by Getty Images

But now, as the Palestinian Authority moves to crack down on mosques and to remove imams preaching violence, some believe that the Palestinians deserve credit.

“We need to acknowledge the steps they have taken and encourage them to take further steps,” said David Makovsky, director of the Project on the Middle East Peace Process at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, which is a think tank widely seen as supportive of a two-state solution and is also home to many pro-Israel scholars. “There is no doubt that we are looking at a qualitatively different approach compared to the Arafat era,” he added, stressing that despite progress, Palestinians still have a long way to go.

Attitudes toward the issue of incitement split largely along political lines. Supporters of the Palestinians highlight the mosque program as a sign of progress, while Israel advocates cite a recent report sponsored by the P.A., denying any Jewish connection to the Western Wall, as evidence that nothing has changed.

But amid all the debate, what is most striking is the absence of any clear, agreed-upon definition of what constitutes incitement. Little consideration is given, as well, to Israel’s own anti-incitement obligations, as outlined in the Middle East Roadmap for Peace, accepted by both Israeli and Palestinian leaders.

“The debate is completely disconnected from the facts,” said Nathan Brown, a George Washington University political scientist who has researched the issue of incitement in the Palestinian press and textbooks. “Therefore, it will not go away, no matter what the Palestinians do.”

The key achievement Palestinians offer in response to claims of incitement is the clampdown on Friday sermons in West Bank mosques. These sermons, documented by watchdog organizations, were known to include hateful speech about Jews and Israelis, calls for jihad, and praise for terror and violence.

“Wherever you are, kill the Jews, the Americans, who are like them, and those who stand by them,” declared one preacher at the Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahayan mosque in Gaza in an October 13, 2000 sermon highlighted by the Middle East Media Research Institute, a pro-Israel group that translates public discourse in the Arab world into English. It is but one of many examples the group has offered.

In a process that began three years ago, the P.A., which is controlled by the Fatah faction, put the mosques under supervision of its Ministry of Waqf & Religious Affairs. The ministry, in turn, began to screen imams and basically removed those who did not adhere to the Fatah line. The P.A. also launched courses for the training of new imams and continues to put out guidelines for sermons.

“I’m watching these things 24 hours a day, and I don’t see any incitement in the mosques in the West Bank,” said Bassem Eid, founder and director of the East Jerusalem-based Palestinian Human Rights Monitoring Group and a frequent critic of the P.A. Eid said he is “very satisfied” with the speeches imams now give on Fridays.

Most experts following the issue agree that Fatah, as the P.A.’s dominant component, was motivated to clamp down on West Bank mosques in order to curb the influence of Hamas, its political rival, and not necessarily to uproot incitement. Ghassan Khatib, director of the P.A.’s Government Media Centre, agreed with this analysis but said that the wish to end incitement and to adhere to previous agreements with the Israelis also played a role.

But improvement is, to a great extent, in the eyes of the beholder.

Critics of the P.A. say the change is limited, that imams were replaced in only high-profile mosques and in those where the sermons are carried live on TV. Also, they say, even the new rhetoric used by imams is far from promoting peace.

Yoram Meital, chairman of the Chaim Herzog Center for Middle East Studies and Diplomacy at Ben-Gurion University, said much of the new language in mosques now focuses on the issue of Jerusalem, and has included claims that Israel plans to demolish the Al-Aqsa mosque.

“It’s a shift from incitement against Jews and Judaism to something that is much more specific, much more difficult to control as it connects up with the [P.A.] political discourse,” Meital said.

The issue of incitement was first raised in the 1993 Oslo Accords and has been present ever since on the Israeli-Palestinian agenda. The 1998 Wye River memorandum called for the establishment of a joint Israeli- Palestinian committee “to monitor cases of possible incitement to violence and terror.” The committee was short lived, and the idea was revisited several times later but never produced results. The 2003 roadmap for peace requires both Palestinians and Israelis to end incitement against the other side by official institutions, as part of the first phase the plan offers toward a two-state solution.

Citing this commitment, Palestinians say that their own complaints about incitement from the Israeli side are all but ignored, or quickly dismissed as passing aberrations.

Husam Zomlot, deputy commissioner of the International Relations Commission of Fatah, the ruling party in the P.A. government, pointed, among other examples, to long-standing positions advocated by Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman calling for Israel to swap land containing large numbers of Palestinians to the P.A. in negotiations that are expected to include land exchange arrangements. This would effectively strip hundreds of thousands of Palestinians of their Israeli citizenship.

“It is a form of incitement when talking about exchanging populations because you do not want [a certain population] in the state,” he said.

And in a kind of reversal of Israel’s charge that Palestinians deny the existence of Israel and the Jewish people’s historic ties to Jerusalem, Zomlot noted that Israel’s Ministry of Tourism continues to publish maps that depict the occupied territories as part and parcel of Israel itself.

Part of the problem is that none of the international plans calling for the ending of incitement offer a clear definition of the term.

For Palestinians, according to Khatib, incitement means “any behavior or statement or position that would encourage hatred, hostility and violence.”

Israel’s current definition of incitement is much broader. It includes not only encouragement of violence, but also denial of peace education, demonization of Israel, denial of Israel’s right to exist as the nation state of the Jewish people, denial of Jewish links to Jerusalem and glorification of terror, a term relating to the naming of streets and squares after terrorists.

This definition was formulated by the Strategic Affairs Ministry’s deputy director-general, Yossi Kuperwasser, who is in charge of the issue of incitement. Kuperwasser recognizes that Israel’s far-reaching definition, in contrast to the more limited definition of incitement used by the P.A., puts large parts of the mainstream Palestinian narrative in the realm of incitement. In his view, the mainstream narrative does contain incitement, and he sees this as a problem standing in the way of peace. Solving the issue of incitement, he believes, “requires a change of the Palestinian narrative.”

One source for Kuperwasser’s index are reports put out by Palestinian Media Watch, a group that monitors closely the Palestinian press in search for incitement. Itamar Marcus, the group’s founder and director, believes the Palestinian Authority deserves no credit for its action on the mosques. “The problem is not mosques, it is the glorification of terror,” he said. His Palestinian Media Watch reports are full of examples to prove his point: Naming sport tournaments and summer camps after terrorists, running TV game shows in which students are encouraged to name Israeli cities as occupied Palestinian towns, and ignoring Israel in textbooks and educational material.

“There is a total atmosphere of hate” in the Palestinian Authority toward Israel, he said, “absolutely no recognition, non-stop hate, and glorifying of terror.”

Marcus warned that school textbooks issued by the Palestinian Authority “are the worst we’ve seen” since they accuse Israelis of “stealing Palestine.” “When you keep pumping hate to people, it will eventually come out in the form of violence,” he warned.

The content of Palestinian school textbooks has, indeed, been part of the debate over incitement ever since the peace process began. And it has been dizzying to follow.

In his 2001 research paper on this topic, Brown, the GWU political scientist, found that new textbooks in use at P.A. schools “have removed the anti-Semitism present in the older books. While they tell history from a Palestinian point of view, they do not seek to erase Israel, delegitimize it or replace it with the ‘State of Palestine’….the new books… do not compare unfavorably to the material my son was given as a fourth grade student in a school in Tel Aviv.”

A subsequent report by the Center for Monitoring the Impact of Peace, an Israeli group, countered Brown, offering instances of anti-Semitism it found in textbooks still in use in Palestinian schools. Brown criticized the center for failing to note that these examples came “from the Jordanian and Egyptian books that the PA was working to replace.” He noted that Israel had used these same books in East Jerusalem schools.

A 2006 study by the Israeli Defense Ministry delivered findings similar to CMIM. But a 2002 study done jointly by researchers from Hebrew University’s Harry S. Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace and Bethlehem University, found that the P.A. books “portray Jews throughout history in a positive manner” while modern-day Israelis “are presented as occupiers.” The texts include examples of Israelis killing and imprisoning Palestinians, demolishing their homes, uprooting fruit trees, and confiscating their lands and building settlements on them, the study noted.

By comparison, the joint researchers found that the existence of Palestinians as a people was not even acknowledged in a sample of Israeli textbooks while “disputed territory is presented as being part of Israel.”

Palestinians had suggested that both sides move together to add recognition of the other state in their respective curriculums. Kuperwasser rejected this idea, saying that a Palestinian state does not exist. “We can’t put ‘Palestine’ where there is no ‘Palestine,’” he said.

The other hot topic being discussed is the naming of streets and squares after terrorists. A recent survey conducted by The Israel Project among Palestinians in October found that a majority of Palestinians hold warm views toward Dalal al Mughrabi, a Palestinian terrorist responsible for the killing of 37 Israelis. Recently the P.A. named a summer camp after Mughrabi.

Palestinians have pointed in response to Israeli cities and streets named after Jewish fighters who targeted civilians before the establishment of the State of Israel. In Akko, for example, Shlomo Ben-Yosef Street and the Street of the Two Eliahus memorialize, respectively, an Irgun terrorist who attacked a bus of Palestinian civilians in 1938 and Eliyahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet-Zouri, the murderers in 1944 of Lord Moyne, the British minister resident in Egypt.

“War criminals of one side are the heroes for the other,” Khatib said, but Kuperwasser, on the Israeli side, rejected the notion, saying, “We don’t have terrorists.”

In the United States, none of the debate over incitement and over the measures taken by the Palestinians seems to have reached the Jewish community, where the issue still tops the advocacy agenda for many groups.

Makovsky said that when speaking to Jewish crowds, he encountered real concern over the issue. The Middle East scholar said that the community is right in focusing on the issue, but “it must realize this is not the only metric” and that on some issues, like mosques and teachers, the P.A. has made a change. “It’s important that we don’t throw out the baby with the bath water,” he said.

Most major organizations see no need to change their approach to the issue. Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, said that just as his group speaks out against rabbis who voice racist views, it also calls for an end to Palestinian incitement. “It’s better than it was in the past, but still far from where it needs to be,” Foxman said, adding that actions like naming a square after a terrorist send a stronger symbolic message than “taking a paragraph out of a textbook.”

Larry Cohler-Esses contributed to this report from New York.

Contact Nathan Guttman at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.