Our Fight on Mount Soledad

When did separation of church and state become a slogan rather than a core element of the American way of life? When did a cross become an ecumenical symbol that is appropriate for military memorials on federal property?

Regrettably, these questions remain unanswered — and our courts have not provided much in the way of clarity. This pattern continues with the federal appeals court ruling earlier this month regarding the cross on San Diego’s Mount Soledad.

The involvement of the Jewish War Veterans as a plaintiff in the Mount Soledad case is part of our ongoing fight for the rights of Jewish service members and veterans and on behalf of the values enshrined in the Constitution.

Back in 1986, JWV filed suit to remove or relocate a brightly lit, 65-foot-high memorial cross at Camp H.L. Smith, a Marine Corps base in Hawaii. In 1988, a federal district court decided in favor of JWV, ruling that the cross violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. The federal government did not appeal this definitive decision.

Yet in the years that have followed, this decision has been largely sidestepped.

Take, for example, last year’s Supreme Court ruling regarding a cross in California’s Mojave National Preserve. JWV filed an amicus brief in that case, which involved an 8-foot-tall cross honoring American service members who died in World War I. In response to a federal district court ruling that the cross violated the Establishment Clause, Congress had transferred the plot of land to a local veterans’ group. Federal courts, however, rejected this end-run around the ruling. The federal government appealed the case to the Supreme Court, which in a 5-4 decision overruled the lower court’s decision against the land swap without taking a position on the larger constitutional issue. It sent the case back to the lower courts to sort out.

The January 4 ruling in the Mount Soledad case similarly failed to produce a clear-cut outcome.

The battle over the Mount Soledad cross has been raging for two decades. The 29-foot-tall cross was erected in 1954 and sits atop a peak in a public park. It was dedicated on Easter, and the spot had long been used for Easter services. Once the cross started drawing challenges in court during the late 1980s, its defenders began stressing that the cross was actually a memorial for all veterans.

California state courts had held that the cross represented an impermissible blending of religion and state. So the cross’s supporters had the property turned over to the federal government. JWV filed suit, demanding the cross’s removal or relocation. After losing before a district court, we appealed to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that the present arrangement is unconstitutional.

But the appeals court added in some weasel-wording in referring the case back to the lower court: “This result does not mean that the Memorial could not be modified to pass Constitutional muster nor does it mean that no cross can be part of this veterans’ memorial. We take no position on those issues.”

So, once again, instead of resolving the issue, we end up with a vague and indecisive referral back to the lower courts. This is how the status quo has persisted for so long, with the First Amendment sacrificed to apathy, indecision and — yes — fear.

On the battlefield, we do not serve as members of one religious group or another. We fight, we die, we suffer injuries — and we do so as members of America’s armed forces.

At a military cemetery, each veteran may have a headstone reflecting his or her individual religious preference, and that is as it should be. But veterans, and those who gave their lives for this country, should not have another religion’s symbol foisted upon them. That is not the way to honor them.

This has not been an easy fight for Jewish veterans. The responses we have been getting since the Mount Soledad decision range from those asking why we are making such a fuss to accusations that we are anti-Christian. Even among Jewish veterans, there are those who worry we are disturbing their relationships with other veterans and veterans’ organizations.

Indeed, sometimes it might seem easier to avoid trouble. Just like you can try to avoid accusations of dual loyalty by keeping quiet about your Jewish identity. And you can choose to passively accept proselytizing in our military academies. But ducking this issue would be an abrogation of our duties, not only to Jewish veterans and service members, but also to our Constitution.

Robert Zweiman is a past national commander of the Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America and a current member of its national executive committee.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Make a Passover Gift Today!

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion What Jewish university presidents say: Trump is exploiting campus antisemitism, not fighting it

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Pope Francis’ final speech called for ceasefire and hostage release in Gaza war

-

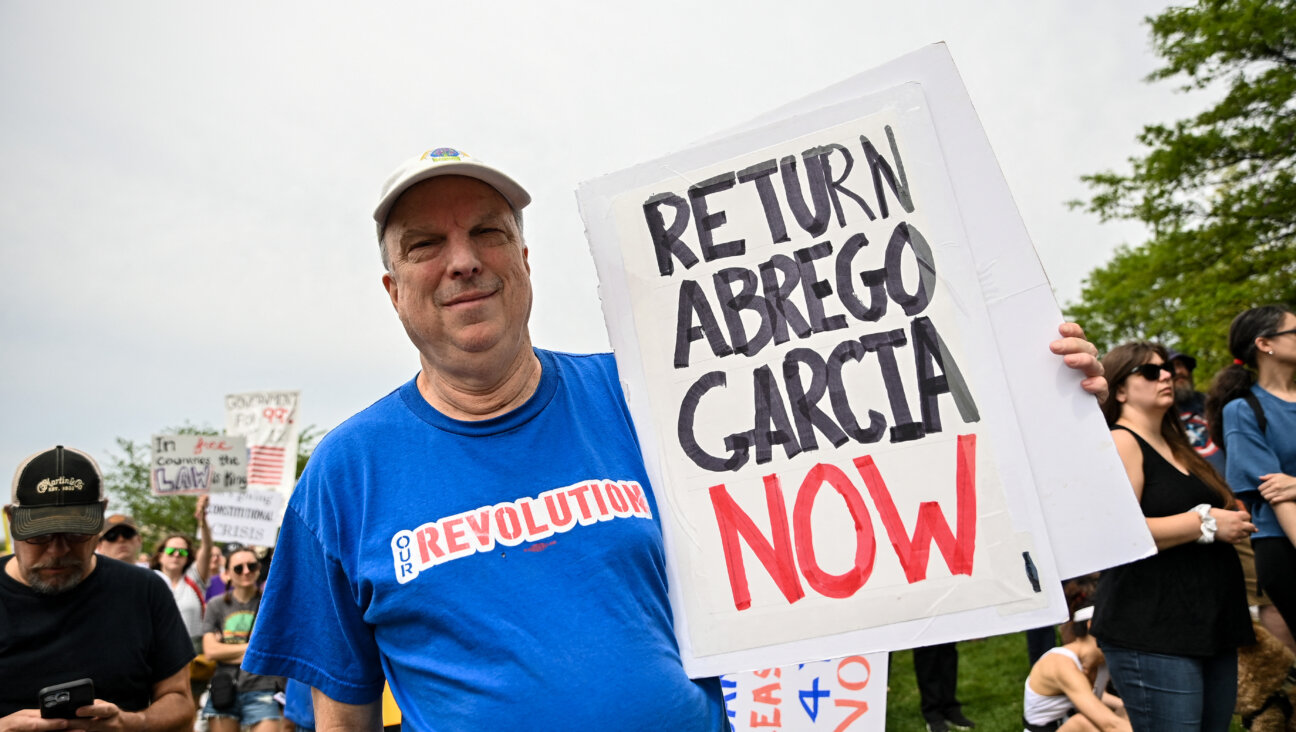

Opinion Shackled, imprisoned and subjected to false accusations, Kilmar Abrego Garcia recalls the fate of Captain Alfred Dreyfus

-

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

-

Culture In Pope Francis, a voice for interfaith dialogue and against antisemitism

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.