Interdependent Minyanim

A saving grace of Jewish prayer is the way it is decentralized. It is not required to take place in a certain space or structure, nor is it dependent on a specific, sanctioned leader. Just 10 people (10 men, for the Orthodox) are really all that’s needed — a minyan, along with prayer books, a Torah, whatever personal ritual items one uses, and wine for Kiddush.

The expansive, multi-purpose building we have come to associate especially with the suburban synagogue, the “shul with a pool,” is a relatively modern invention. “Judaism has always been a religion of grassroots community organizing, and the rabbinic model of the 20th-century synagogue is perhaps the most foreign to the traditional Jewish heritage,” writes Rabbi Elie Kaunfer in his book “Empowered Judaism.”

And he should know. As one of the co-founders of Kehilat Hadar, a successful, lay-led worship and study community on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Kaunfer is on the leading edge of one of the most sought-after groups of rebels in Jewish life right now — independent minyanim with members in their 20s and 30s. Since many of these do-it-yourself groups are more akin to Conservative Judaism than to any other denomination, the Conservative movement is especially eager to bring them into the fold. No wonder: The movement’s own report says that in 2010, only 9% of adult members of Conservative congregations were under the age of 40. On a Shabbat morning at Hadar, 30 seems old. Most Conservative synagogues can only dream about that.

But as our Josh Nathan-Kazis reports this week, many independent minyanim have no interest in affiliating with this or any other denomination. “We don’t need the movement,” one minyan leader boasted. Perhaps not the “movement” as it is now structured, but engaged Jews — from establishment and upstart congregations — need to find a way to work together to shape a common future, especially if committed, egalitarian, non-Orthodox Judaism is going to survive. To do that, they must stop talking past one another and recognize some central truths.

Independent minyanim are a response to a problem, not the cause of it. These alternative prayer communities — like the havurot from the 60s and 70s, like many do-it-yourself worship groups that meet without fanfare today — grew out of a need that large, fancy, pricey synagogues failed to meet: the need for more spiritual prayer, for intimate relationships with people committed to learning and observance, and for the chance to participate, not just sit passively while the cantor sings and the rabbi sermonizes and much of the congregation fidgets.

It is true, as some bemoaners suggest, that independent minyanim tend to draw the most educated and engaged Jews away from traditional congregational worship. But is this any surprise? These are the Jews taught Hebrew at a young age, davening skills in day school and summer camp, leadership skills at Hillel, all strengthened by extended stays in Israel. Add to that this younger generation’s dislike of labels and hierarchy, its facility for organizing, and its romance with the new, and it’s only a wonder why there aren’t more independent minyanim than the 60 or so found in a 2009 survey that Kaunfer cites.

Offering independent minyanim an opportunity for affiliation, as a new draft strategic plan for the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism suggests, is nice but misses the point. It is synagogues themselves that need to change to attract this sought-after demographic. Whether that can be done by dramatically rethinking the role of religious leadership, the structure of dues, the very ethos of many congregations remains to be seen.

But this rapprochement will not occur unless independent minyanim also embrace their broader responsibilities. Imperfect though they may be, synagogues are still the cornerstone of American Jewish life, anchoring a community by bringing together Jews with differing needs and motivations, allowing the veteran day-school parent to brush up against the loosely affiliated newcomer and the grandparent to help out in the nursery school. Even if well-trained volunteers can lead every service, a rabbi is still essential for pastoral care, teaching, religious guidance and communal leadership. Even if synagogue buildings are too big and impersonal, they still are the Jewish face on the block, a welcoming site to strangers and a symbol of neighborly permanence.

In a section of his book laying out challenges for independent minyanim, Kaunfer points to the need for these groups to do more than offer compelling Shabbat services. “But what about daily minyan, regular Torah study, engagement with Israel and questions of peoplehood?” he asks. To which we’d add: What about attending a shiva minyan for an elderly congregant who is otherwise alone? What about paying dues to keep the lights on and the building heated, and to subsidize a needier member?

Being part of a Jewish community is about more than satisfying our personal needs and those of our peers. It’s about contributing to the larger good, outside of our control or purview. As Kaunfer himself acknowledges: People join independent minyanim “out of inspiration, not obligation. But obligation and responsibility are age-old Jewish values.”

Indeed, they are.

The growth and strength of independent minyanim, their sought-after presence, all this belies a deeper truth: They represent only a fraction of American Jews, and likely always will. Belonging to a lay-led participatory minyan demands more time, energy and education than most Jews have or can give. That is why constructive dialogue between and among those who wish to live vibrant Jewish lives is so crucial. Let independent minyanim serve as an inspiration — not to forget our larger obligation to the Jewish people.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Make a Passover Gift Today!

Most Popular

- 1

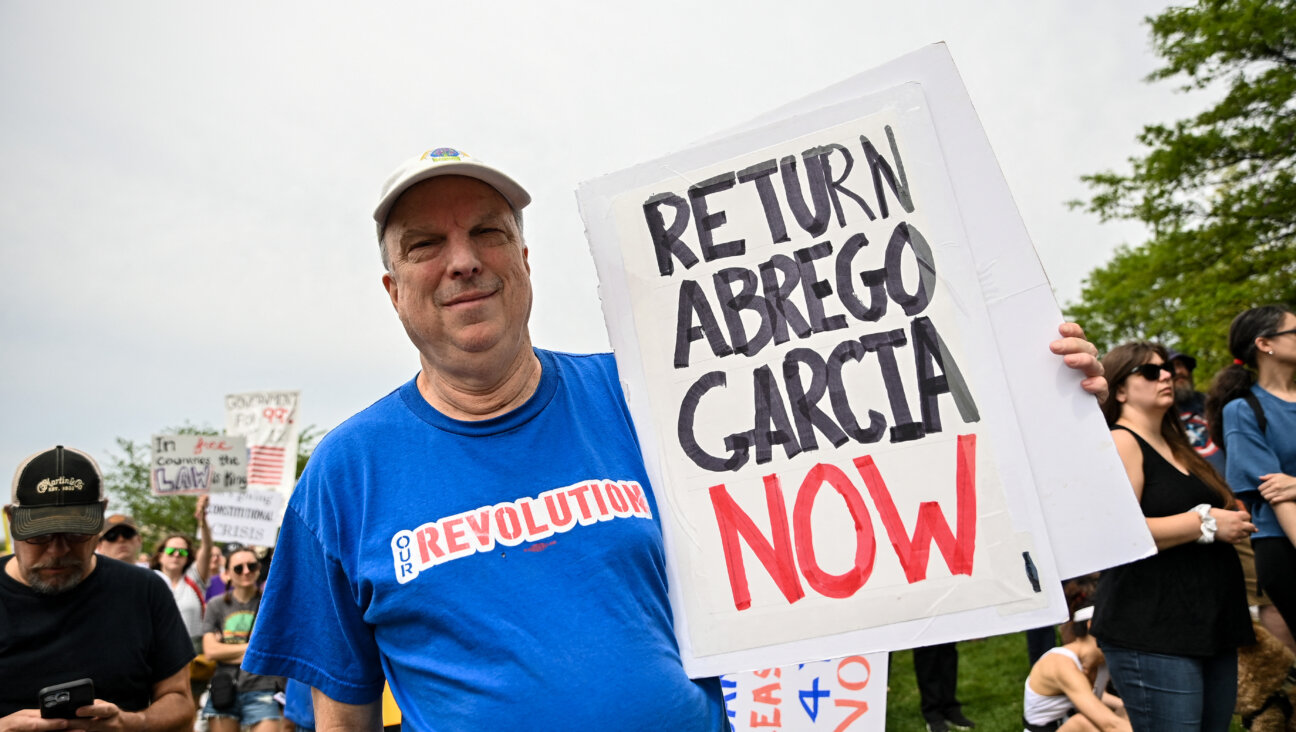

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Opinion What Jewish university presidents say: Trump is exploiting campus antisemitism, not fighting it

- 4

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Harvard president: As a Jew, ‘I know very well’ that concerns about antisemitism are valid

-

Fast Forward Ben Shapiro, Emily Damari among torch lighters for Israel’s Independence Day ceremony

-

Fast Forward Larry David’s ‘My Dinner with Adolf’ essay skewers Bill Maher’s meeting with Trump

-

Sports Israeli mom ‘made it easy’ for new NHL player to make history

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.