Peace Can’t Be Provisional

Israel needs to achieve an end to its conflict with the Palestinians. Recent developments in the region make this goal all the more urgent.

Yet instead of working to achieve a permanent-status agreement, ending all claims by the two parties, we are increasingly hearing talk about pushing for an interim agreement based on provisional borders. This would be a profound mistake.

The contours of any permanent-status agreement between Israel and the Palestinians are already well known. Any such agreement would generally follow the Clinton Parameters, with a Palestinian state being established roughly along the 1967 lines and agreed-upon land swaps so that Israel could take in the majority of its settlers. The Palestinians would need to abandon the notion of a return of Palestinian refugees to Israel. But Israel would have to pay a price, too: namely, the establishment of a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem’s Arab neighborhoods and the relocation of some 100,000 settlers who live deep inside the West Bank.

Even though the outlines are clear, achieving such an agreement will require real political courage. Indeed, any agreement along these lines would meet stiff resistance from within Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s own party and from his right-wing coalition.

That is why many expect that Netanyahu, who has promised to unveil a new peace initiative in the coming months, will instead choose to embrace the idea of establishing a Palestinian state within provisional boundaries. This would mean putting off the tough decisions needed to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict once and for all.

The Palestinians, for their part, are unlikely to accept an interim agreement of this sort. They know that the reality on the ground in the West Bank would only be slightly changed. After all the ceremonies, the feeling in the West Bank, Gaza and in the Palestinian diaspora would be one of overwhelming frustration.

But even if the Palestinians were to accept a state within provisional borders, the outcome would still be bad for Israel. An Israeli-Palestinian agreement without a final demarcation of mutually recognized borders, without resolving the core problems, without an end of claims and an end to the conflict would only keep the wound open.

Jerusalem, in particular, would remain a focus of conflict. Jerusalem can thrive only as a city of peace, where people make pilgrimages and visit, and where international conferences convene. As a city of continued confrontation, Jerusalem will suffer socially and economically.

It seems unlikely that Netanyahu would propose dismantling settlements under any interim agreement. If all the settlements were outside the provisional borders of the Palestinian state, this state would consist of dozens of disconnected enclaves — an unviable state. If settlements were left within the provisional borders of the Palestinian state, then the Israeli army would need to be stationed within the state’s territory to protect the settlers. Either way, Israelis would continue to be condemned as occupiers. Israel’s international and regional isolation would continue to grow. And terror organizations, backed by Iran and Al Qaeda, would continue exploiting the conflict for their evil purposes.

Only a permanent and comprehensive agreement with the Palestinians can meet Israel’s urgent needs. It is the only way of reversing our growing international isolation. It is the only way of changing the state of affairs in Gaza, where the Iranian-backed Hamas regime stands to benefit from the revolution in Egypt and could create an intolerable situation for Israel. It is the only way of improving our position in a rapidly changing Middle East and building bridges to the regional forces of modernity and democracy that are now struggling to reshape their societies. Above all, it is the only way of permanently heading off the threat of a bi-national state in which Jews would eventually not be the majority.

We should not be making proposals that we know would be rejected by the Palestinian side and would, in any event, only prolong our conflict. If Netanyahu lacks the backbone to challenge his coalition partners in order to secure Israel’s future, he should have the courage to call new elections and let the Israeli people decide whether they want a one-state solution — which would not be a Jewish state — or a two-state solution.

Ephraim Sneh, a retired general in the Israel Defense Forces, has served as Israel’s minister of health, minister of transportation and deputy minister of defense. He is currently chairman of the S. Daniel Abraham Center for Strategic Dialogue at the Netanya Academic College.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

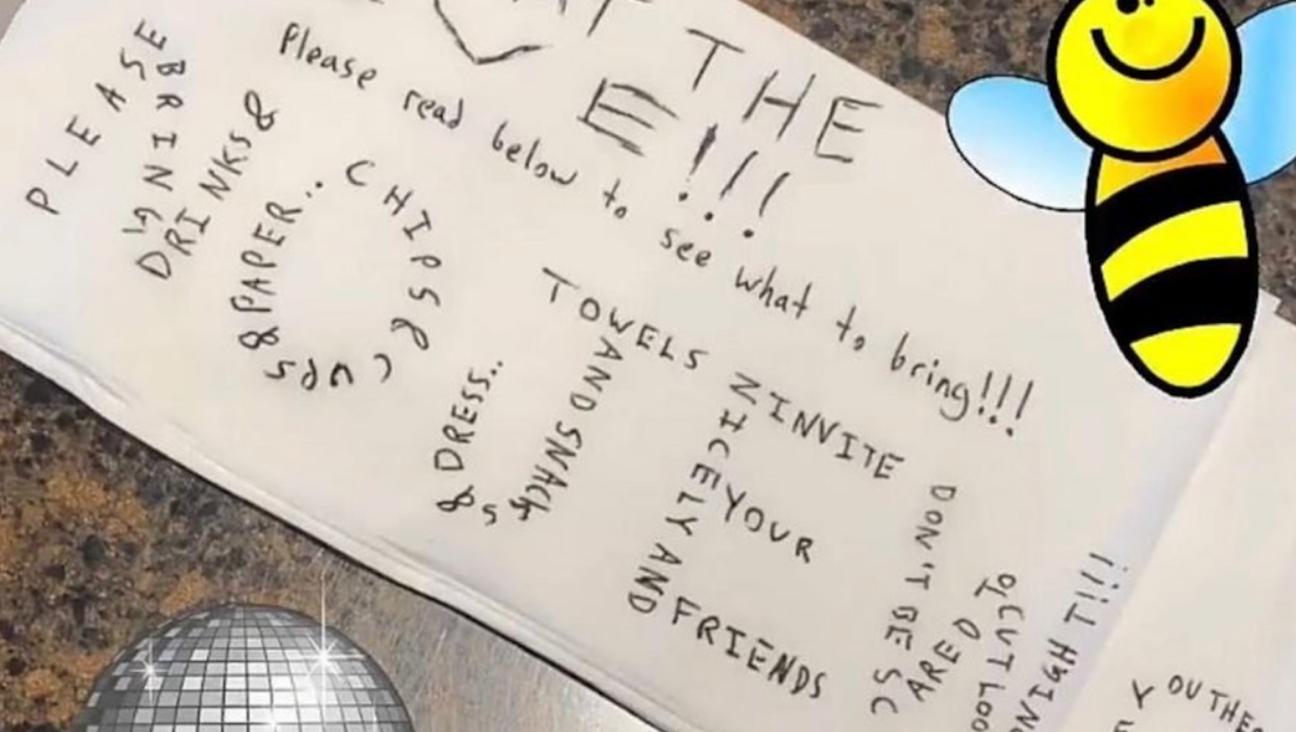

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

News These are the most influential Jews in Trump’s first 100 days

-

Fast Forward Nike apologizes for marathon ad using the Holocaust phrase ‘Never Again’

-

Opinion I wrote the book on Hitler’s first 100 days. Here’s how Trump’s compare

-

Fast Forward Ohio Applebee’s defaced with antisemitic graffiti reading ‘Jews work here’

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.