The War on Dignified Retirements

It’s a remarkable coincidence that the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire follows so closely on the heels of the great Wisconsin labor awakening. Like the yearly coincidence of Purim and St. Patrick’s Day, with their overlapping themes of national redemption and drunken revelry, the Wisconsin-Triangle convergence raises a host of fundamental questions about the nature of our society and the mutual obligations of individual and community.

Here are a few: Has a century of progress made unions and collective bargaining obsolete? Is it really progress when we eliminate workplace disasters by eliminating workplaces? Can we say we’ve learned the lessons of the Triangle tragedy if half of us have learned that rich and poor alike deserve equal access to health care and parental leave, while the other half want to bring back the good old days when workers knew their place and owners were free to run their businesses as they wished without interference from pesky regulators and unions?

In Wisconsin, alert readers recall, Republicans and Democrats are locked in battle over the rights of public employees to bargain collectively through unions. Republicans, speaking on behalf of the employer, namely the ordinary taxpayer, want to restrict bargaining to the dollar amount in the employee’s paycheck and keep the union out of matters that they see as nobody’s business but the employer’s, such as employee health coverage, working conditions and pensions. Democrats, speaking for the employees, meaning many of those same taxpayers, maintain that the unions are entitled to bargain over those benefits, particularly since they have already shown good faith by conceding all the employers’ other demands in advance.

The struggle is part of a furious national debate over compensation and union rights for federal, state and local government employees. There are some 23 million in all, just under one-sixth of all employed Americans. They include park rangers, trash collectors, police officers, restaurant health inspectors, child welfare investigators and prison guards, but most of the public’s attention — and criticism — is focused on teachers.

Why teachers? Perhaps because of bitter memories, buried deep in our national subconscious, of mean old Mrs. Schwartzman in seventh-grade science who assigned too much homework. Classroom memories fade, but the wounded child has re-emerged years later as an angry taxpayer, incensed at the idea of Mrs. Schwartzman retiring in comfort to Florida. Memories of science class cut deep. Maybe this is the real reason for all the talk about “class warfare.”

Lately the debate has come to an emotional head around the charged issue of Mrs. Schwartzman’s pension. Apparently her condo in Boca Raton is what is bankrupting state treasuries from coast to coast. And you thought it was the subprime mortgage crisis and the collapse of the American economy. Silly you.

Pensions of the sort teachers receive, paying a fixed monthly retirement income for life, used to be widespread. A generation ago they covered about half of all American workers, after rising steadily since the 1930s. For the first time in American history, old age was no longer synonymous with poverty.

Since pensions peaked in 1979, however, companies have been dumping the plans in a stampede, claiming they’re too expensive. Today only 19% of private-sector workers have pensions with a defined payout, according the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Instead, companies that still have any retirement plan at all usually offer what’s called a defined-contribution plan, better known as an IRA or 401(k). That’s where you get a tax break to put your own money away and hopefully save enough so that when you retire you can live on the interest. Frequently the company matches a fraction of your payment, but it’s a bargain compared to what firms had to put aside for traditional pension plans. Mostly the workers are on their own, and the picture isn’t pretty.

About half of all working Americans today have one of these self-service retirement accounts through their job. According to the Federal Reserve, the median balance in these accounts in 2004 was $60,000, enough to yield a princely retirement income of $400 per month. And that was before the crash. After 2008 the average account lost about one-third of its value.

Even in “the most optimistic view of 401 (k) holdings,” the Fed reported in 2004, a worker with a median income of $50,000, saving diligently for 30 years, can hope to amass a balance of $145,000, which “even when combined with Social Security will not produce adequate replacement” for his working salary — that is, not enough to live on. In other words, these accounts just don’t work.

Among public employees, nearly 80% have old-fashioned, defined-benefit pensions. The vast majority of them manage, like Mrs. Schwartzman, to retire with dignity. (It’s no coincidence that about 35% of public employees belong to unions, compared to 7% of private-sector workers.)

But for the rest of the workforce, the five-sixths in the private sector, prospects are darker. The bottom line: Of 75 million baby boomers approaching retirement age over the next two decades, more than half face a future of severe hardship.

Now, the Republican governors in Wisconsin, Ohio, Idaho and elsewhere aren’t dumb. They recognize a crisis when they see one. But the crisis they see isn’t the millions of Americans nearing retirement age without a means of support. The crisis is that their own employees still have pensions.

To be fair, states face a genuine fiscal crisis. State pension funds have a combined $1 trillion gap between what they have amassed and what they’ve promised in future payments. This isn’t due to extravagant union demands, though. The trouble is that during the bubble years the pension funds invested their holdings in risky stocks to get higher returns. That allowed states to put less into the pot and lower taxes. Unfortunately, the crash blew a big hole in those plans.

The only options now are to raise taxes back up or to cut their employees’ future lifeline. For Republican governors, it seems, it’s a no-brainer.

So here’s my question: Is that the kind of country we want to live in?

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected] and follow his blog at blogs.forward.com/jj-goldberg

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

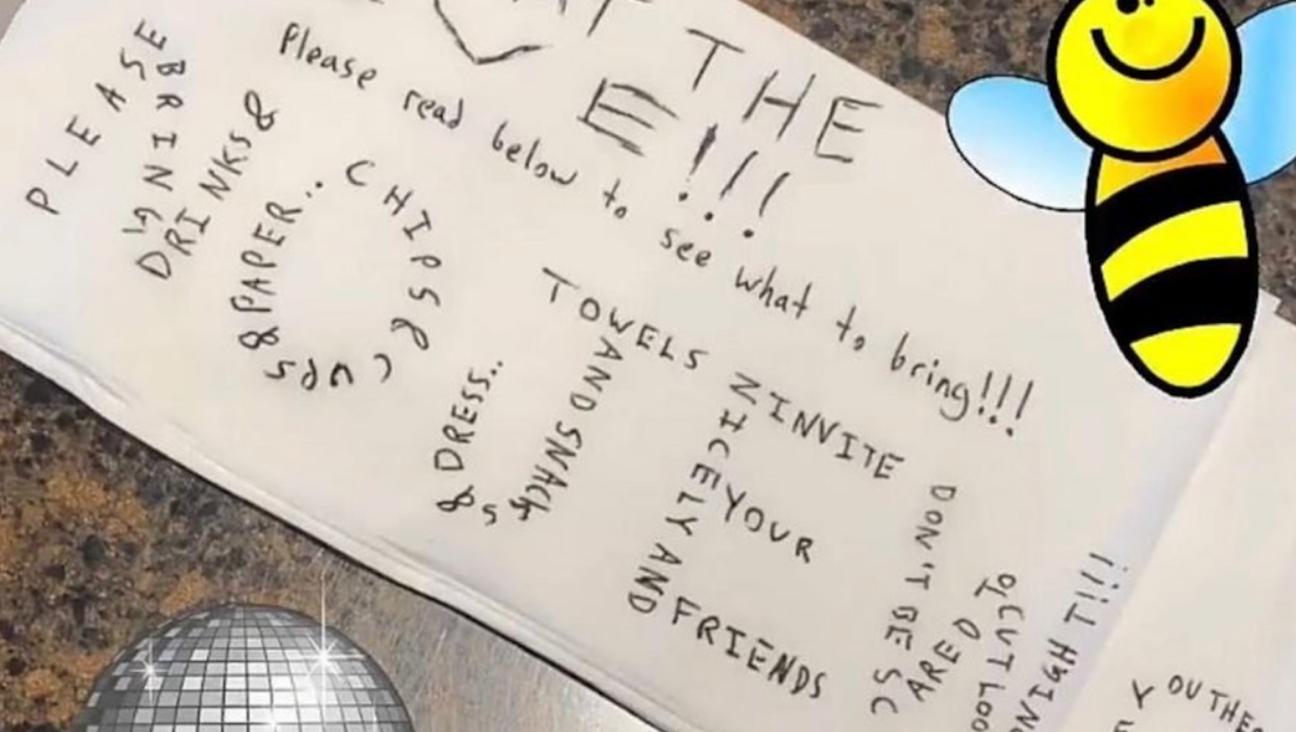

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

News These are the most influential Jews in Trump’s first 100 days

-

Fast Forward Nike apologizes for marathon ad using the Holocaust phrase ‘Never Again’

-

Opinion I wrote the book on Hitler’s first 100 days. Here’s how Trump’s compare

-

Fast Forward Ohio Applebee’s defaced with antisemitic graffiti reading ‘Jews work here’

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.