Our Divisive Discourse

“You say you’re pro-Israel, but you’re really not.”

These words may sound reminiscent of the recent Knesset hearing about J Street. But they’re from an entirely different source: a high school junior we will call “Isaac.”

Long before the Knesset questioned J Street’s activities, Isaac and his 11th-grade classmates were debating what it means to be pro-Israel. At Isaac’s community Jewish day school, where I spent six months observing and interviewing students, Israel was a central pillar of Jewish education. Students and teachers agreed that the school was — and should be — staunchly “pro-Israel.” They disagreed, however, about what being “pro-Israel” meant.

On one side of the spectrum were the students who believed that a pro-Israel school must support the Israeli government no matter its policies. In one teacher’s words, “Either you support everything Israel does or you don’t support Israel.” Others adhered to the belief that as American Jews they had the right to question the tactics of the Israeli government. One of these students explained: “I think that the only viewpoint that’s necessary for being considered pro-Israel is acknowledging that Israel has the right to exist. Beyond that is up for negotiation.”

Upon first glance, it would be possible to mistake students’ disagreements for the kind of enthusiastic engagement that educators hope to foster. After all, Israel was a frequent source of conversation at the school, and lessons often focused on Israeli history, politics and culture. But upon closer look, the constant disagreements about the definition of “pro-Israel” revealed a much more destructive reality.

At first, classmates engaged in verbal battles over how to define commitment to Israel. Rather than accepting the “pro-Israel” credentials of others at the school, there was a culture in which students and teachers were criticized, even ostracized, for their positions about how to express their support. As one high school senior explained, “People will talk about you behind your back because you’re not pro-Israel in the same way they’re pro-Israel.”

As a result, students who had previously been enthusiastic about their own connection to Israel began to censor themselves. While the school encouraged conversations about Israel, students sought to avoid political confrontation and the social stigma that accompanied it. Teenagers on both sides of the ideological spectrum feared being criticized for their beliefs about Israeli politics. As a Modern Orthodox Jew with hawkish political tendencies explained, “I feel very censored here.” Her classmate, a Conservative Jew and avowed leftist, felt the same. “I know this is terrible,” she admitted, “but I try to avoid conversations about Israel.”

Fearing that voicing their beliefs would cause them to be ostracized, even the most committed students began to disengage. The result was that, in a school that placed Israel at the very core of its Jewish education, students felt increasingly ambivalent about Israel and their relationship to it.

This community Jewish day school offers a compelling — if troubling — snapshot of the contemporary American Jewish community’s relationship to Israel. The school’s potential to help students thoughtfully engage with Israel was undercut by a divisive discourse that became fixated upon the question of who counted among the ranks of Israel’s supporters. As a result, even previously committed students — hawk and dove alike — wanted little to do with the Jewish state.

Studies have shown that today’s American Jewish youth are disengaging with Israel. It is particularly troubling that this would be true even at a Jewish day school that stresses engagement with Israel as a priority.

If we want today’s American Jewish youth to participate in Israel’s future, the way we discuss and relate to the Jewish state needs to change. The question “Are you pro-Israel?” is counterproductive, resulting only in exclusion and disengagement. Instead, our schools, synagogues and other communal institutions must focus on teaching our youth about the myriad ways that Jews — in Israel and outside it — can contribute to the development of the state. Only then will today’s American Jewish teenagers truly engage with Israel and the hope of its national anthem: ayin l’tziyon tzofiya. Their eyes will turn once again toward Zion.

Sivan Zakai is a lecturer at American Jewish University’s Graduate School of Education.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

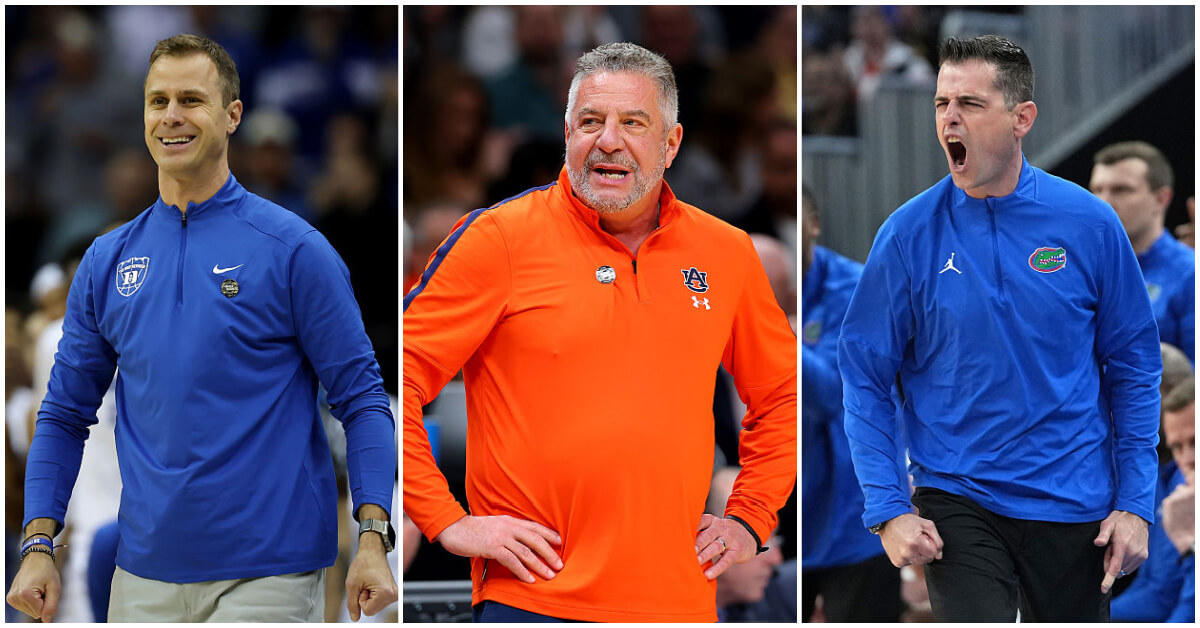

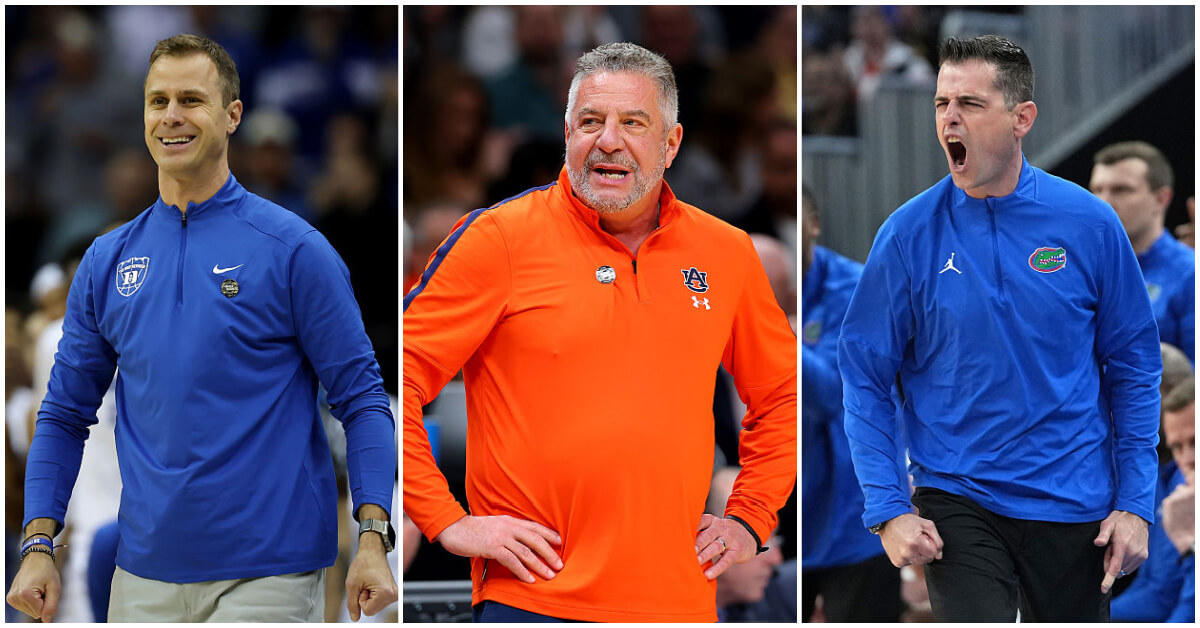

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.