A Man, a Dog and an Author

MOTTI, By Asaf Schurr, Translated from Hebrew by Todd Hasak-Lowy

MOTTI

By Asaf Schurr, Translated from Hebrew by Todd Hasak-Lowy

Dalkey Archive Press, 169 pages, $13.95

MOTTI, By Asaf Schurr, Translated from Hebrew by Todd Hasak-Lowy

It is not obligatory for an Israeli novelist to double as national prophet, but it helps secure publication in the United States, where translations constitute less than 3% of books. Writing about and against public injustice, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Václav Havel and Reinaldo Arenas found American readers. Compatriots who pursued private themes did not. “Motti” is the second of Asaf Schurr’s three novels, but it is the first to be published in English, three years after its release in Israel. Nowhere in “Motti” do the words “Palestinian,” “Hamas” or “settlements,” appear, nor does the novel make reference to conflicts between secularists and Haredim. Except for the fact that he writes in Hebrew, Schurr has little in common with David Grossman, Amos Oz or A.B. Yehoshua, who use their fictions to confront crises of communal identity. Surveying the boundaries of genre rather than those of nation, he is literary landsman to Italo Calvino, J. M. Coetzee and Milan Kundera. Though he sets his story in Israel, Schurr abjures the role of narrative radiologist; “Motti” is not an MRI of his country’s troubled psyche.

Instead it is a short book composed of 58 brief sections, most occupying two or three pages. Epigraphs from Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher of linguistic determinism, signal a novel that is self-conscious about its own verbal medium. “I believe,” the author/narrator says, “that a creation must bear the scars of its creation,” and “Motti” is pocked with the metafictional cicatrices of its verbal origins. Opening with a direct address to its readers, the novel acknowledges its author’s limitations: “You’re the performers and the audience all at once,” the author/narrator tells his readers, “and everything is already out of my control.” Describing the protagonist Motti’s pet dog — named Laika, after the canine casualty of the first Soviet space launch — he renounces any special authority, admitting, “I imagined the Laika in this book as a German shepherd, but everyone else will imagine her as they like.”

If readers are encouraged to imagine, so are characters. A Walter Mitty of the Middle East, Motti is a meek schoolteacher whose vibrant inner life belies his drab outer existence. He fantasizes about romance with a neighbor, Ariella, who lives just the other side of his apartment wall. Though he cannot muster the courage to start a conversation, he dreams up elaborate scenarios of courtship, marriage and even parenthood with her. Just as readers are likely to improvise their own extrapolations from the minimal information that Schurr provides, Motti generates multiple plot lines for his life with Ariella. She becomes by turns a receptionist, a meteorologist and a plastic surgeon, but he actually knows almost nothing about Ariella, except that she is a prepubescent. But he is no more pedophile than Dante, who spun celestial poetry out of a brief encounter with 8-year-old Beatrice Portinari.

Motti’s only friend, Menachem, is as gregarious as Motti is introverted. When, driving home after too many beers, Menachem kills a pedestrian, Motti impulsively decides to take the rap. Menachem, after all, has a wife and children, while Motti is just a solitary schlemiel. The five years he spends in a prison cell, conjuring up plot lines for Ariella, differ little from the life he leads within his apartment walls, imagining the off-screen reality of bit players in movies. A prison guard who passes time by recounting personal experiences offers further evidence of the universal impulse to generate stories; however, the most important story in “Motti” is the transaction between the text and its readers. An apologetic author interrupts the proceedings so often that it is the Motti story that seems an intrusion into the commentary. The author/narrator anticipates that many will dismiss him — and his book — as “a pest, a nuisance, an irritation, etc.” He suggests, however, that “if art has any obligation, if the people trying to make it have any obligation at all, it’s only to be utterly human.” The novel is at its most human when it dramatizes the attractions and distractions of storytelling.

Schurr minimizes the importance of content to his art. “The heart is the sentence,” he explains. “Always the sentence. It doesn’t even matter what I say in it, it’s just the labor that’s important, always this labor, word after word after word….” Todd Hasak-Lowy’s lucid translation is faithful to the original, word after word after word. Following the Hebrew literally, though, he repeatedly renders the if clause in conditional sentences in the future tense: “… if I’ll have kids, he’ll be their doctor too.” Though the Hebrew kmo could mean “like” or “as,” Hasak-Lowy translates it only as “like”: “… like officers in the army are so fond of doing….” This has the effect of making the narrator seem more colloquial and less in command of his carefully crafted sentences than he is elsewhere.

In a typically metafictional moment a third of the way through the book, Schurr likens his novel, containing more spaces than words, to a net: “The body of the plot is full of holes like a fisherman’s net or an old stocking, and as with the net, it gathers up, without discretion, miscellaneous thoughts and meaningless fantasies and so forth.” A spry affirmation of the freedom to imagine, “Motti” is a net gain for Israeli fiction.

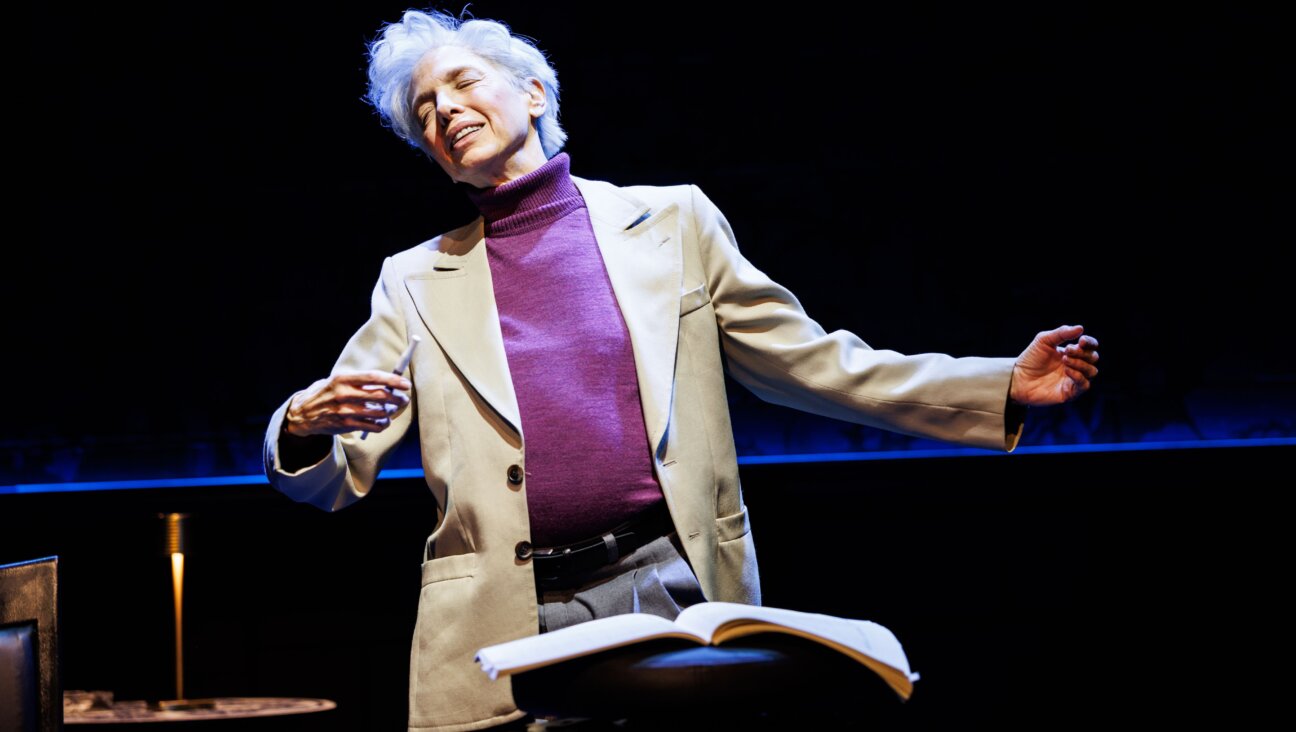

Steven G. Kellman is the author of “Redemption: The Life of Henry Roth” (W.W. Norton, 2005) and “The Translingual Imagination” (University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO