We Will, We Will Rock You

Image by Getty Images

Plus ça change, plus ça reste le même chose. The dispute that has recently arisen in Israel concerning the wording of the Yizkor prayer for fallen soldiers, said on the country’s annual Yom ha-Zikaron, or Memorial Day, reminds one of nothing so much as a similar quarrel that nearly delayed the Jewish state’s declaration of independence more than 60 years ago.

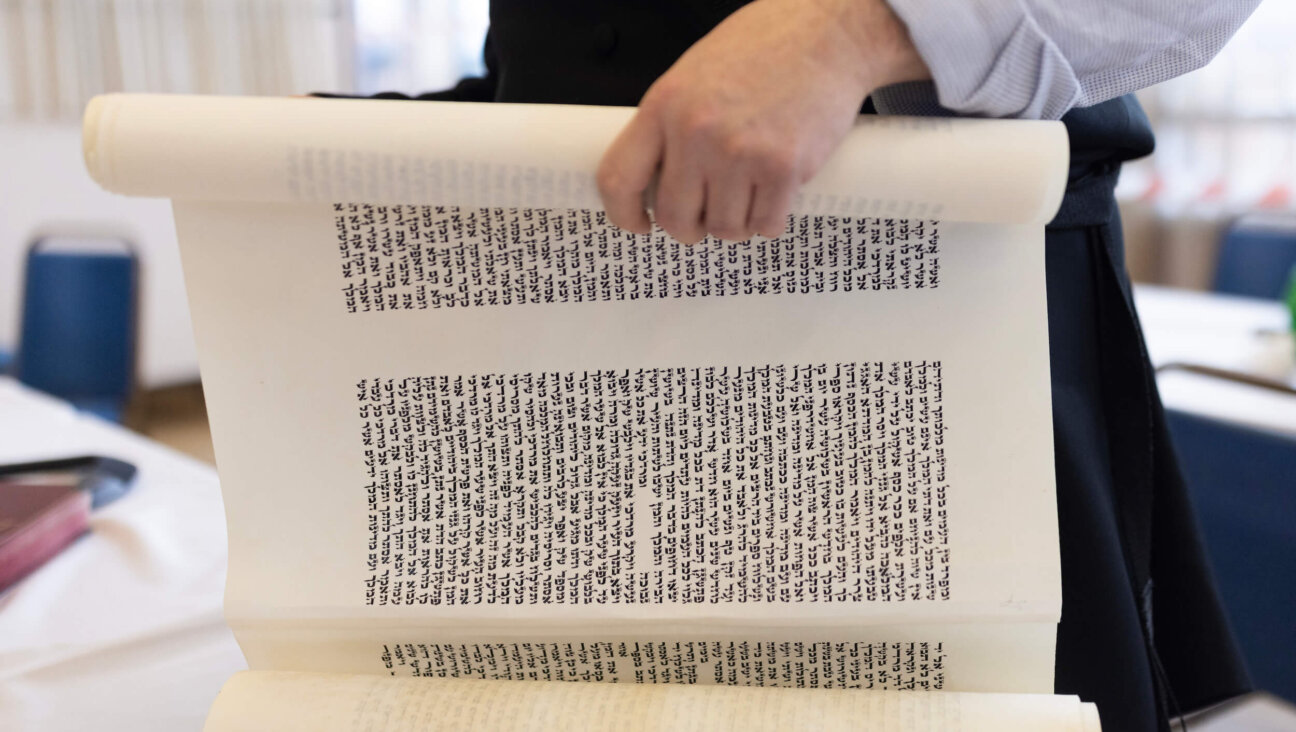

Until not long ago, the Yizkor of Yom ha-Zikaron, recited at a solemn ceremony at the Western Wall and at memorial gatherings all over Israel, began with the words Yizkor am yisra’el, “May the people of Israel remember,” followed by, “its brave and faithful sons and daughters, the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces… who gave their lives in the battle for the restoration of Jewish nationhood [t’kumat yisra’el].” This was based on the traditional Yizkor for deceased family members that is said several times a year in the synagogue and begins with Yizkor elohim, “May God remember.”

And yet, if that’s the traditional wording, as religiously Orthodox Israelis took to protesting, why not use it on Yom ha-Zikaron, too? Why keep God out of it? Even in the Yom ha-Zikaron ceremony, after all, the Divinity is mentioned in the El Malei Rahamim or “God, Full of Mercy” prayer that is sung, as it is in synagogues, after the Yizkor. Where, then, is the logic in not mentioning God in the Yizkor itself? In response to this sentiment, indeed, “God” has widely replaced “the people of Israel” in recent years, both at the Western Wall and elsewhere.

This, however, has led to counter-protests from secular Israelis. Why, they ask, should they have to invoke a God they don’t believe in when honoring their loved ones who fell in battle? One of their most articulate spokesmen has been television journalist Menashe Raz, who has campaigned for restoring “the people of Israel.” Naturally, the Orthodox community has opposed this, and Raz wrote to Israel’s new army chief-of-staff, Benny Gantz, requesting his support. Now, Israeli newspapers report, Gantz has answered Raz, although not with the answer Raz hoped for. God, Gantz ruled, will remain in the Yizkor prayer — at least until the next wave of protests.

One has a sense of déjà vu. In May 1948, as the British Mandate prepared to withdraw from Palestine, and the country’s Jewish leadership, headed by David Ben-Gurion, geared up for the establishment of a Jewish state, an official declaration of independence was hurriedly drawn up. Its drafter, a young Tel Aviv lawyer named Mordecai Boehm who worked for the future ministry of justice, modeled parts of it on the 1776 American Declaration of Independence, including the latter’s frequent references to God as a source of human and national rights — in this case, Jewish national rights.

When Boehm’s draft, however, was shown to Ben-Gurion’s Cabinet members, most of whom were left-wing socialists, there was an outcry over its religious phrasing. Yet the Cabinet also included observant Jews, and Ben-Gurion did not wish to antagonize them, either. In the end, he suggested the compromise of omitting all references to God but one, and retaining that, too, in a veiled form. Whereas the last paragraph of Boehm’s draft had begun, “Placing our firm trust in the protection of Divine Providence,” Ben-Gurion’s amended version went, “Placing our trust in the Rock of Israel, we affix our signatures to this proclamation at this session of the provisional council of state, on the soil of the homeland, in the city of Tel Aviv, on this Sabbath eve of the 5th day of Iyar, 5708 (14th May, 1948).”

Although as an epithet for God, “the Rock of Israel,” tsur yisra’el, occurs twice in the Bible — once in the Book of Samuel and once in Isaiah — Ben-Gurion was leaving his fellow socialists the option of claiming that it referred here to something else, such as the Jewish people’s unshakable destiny or rocklike strength. Not everybody on either side was happy with this, though, and as late as May 13th, a day before the British departure, some of the secularists were still insisting on deleting the words entirely, while representatives of the religious parties were calling for changing them to “the Rock of Israel and Its Redeemer,” which would have eliminated any possible ambiguity. The argument grew heated. Ben-Gurion listened to both sides, announced that he would keep “the Rock of Israel” as it was, and cajoled or coerced all the declaration’s signers to go along with him. (“The Rock of Israel and Its Redeemer,” tsur yisra’el v’go’alo, did, on the other hand, make it into the prayer for the State of Israel that is recited to this day in many synagogues on Sabbaths and holidays.)

Could “The Rock of Israel” or a similar epithet solve the problem for the Yizkor prayer on Israel’s memorial day, too? Probably not. The secular/religious divide is even more pronounced today than it was at the time of the state’s establishment, and such a compromise would be less acceptable all around. Moreover, there are no longer secular leaders who, like Ben-Gurion, have a good knowledge of Jewish sources and a creative sense of the uses to which they might be put. Today isn’t 1948, even if it sometimes seems like it. Plus ça reste le même chose, plus ça change.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO