News of the Carrot, Not Pain of the Stick

Letter from Moshe Rosenblatt to ITO president Israel Zangwill, Kiev 1905. From the Central Zionist Archives. (p. 143)

BREAD TO EAT AND CLOTHES TO WEAR: LETTERS FROM JEWISH MIGRANTS IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY

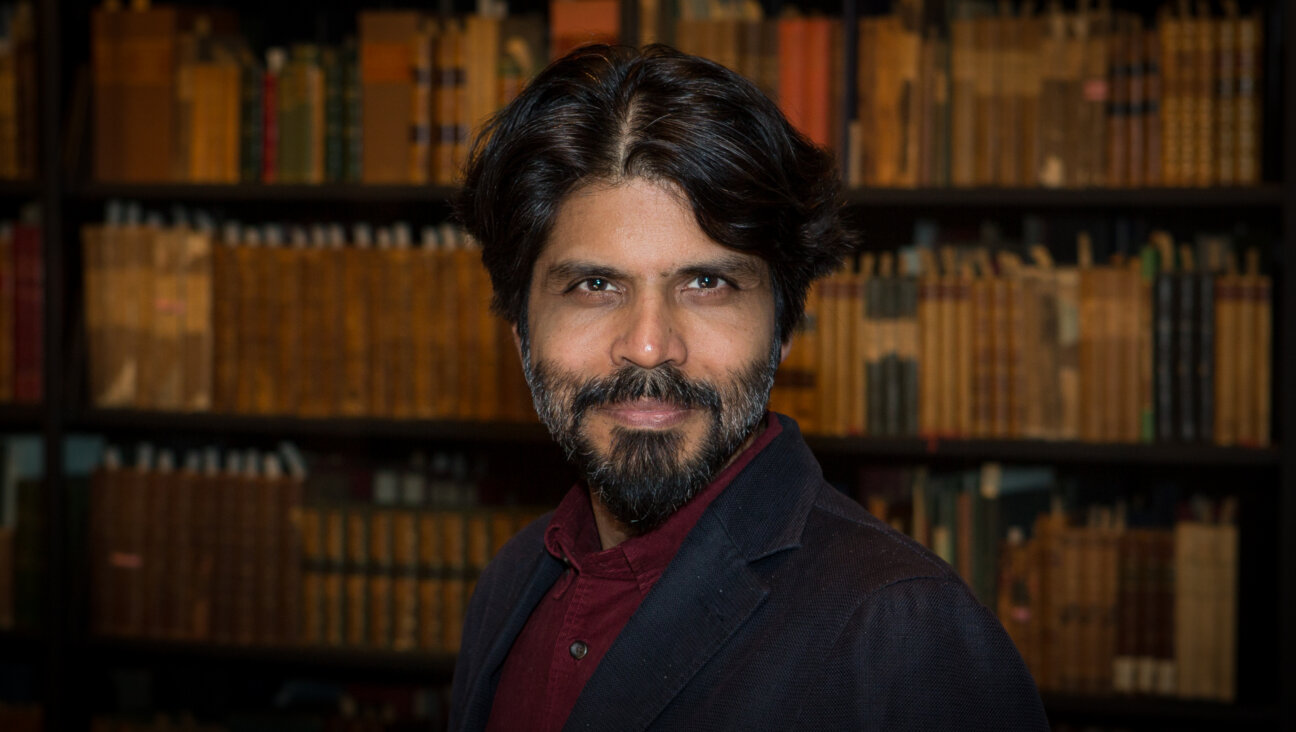

By Gur Alroey

Wayne State University Press, 256 pages, $29.95

You may think you know why your ancestors made their way to this “Golden Land,” but scholar Gur Alroey’s “Bread To Eat and Clothes To Wear” demonstrates that the mass exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe in the early 20th century had less to do with pogroms than casual readers might assume. Alroey shows that “the stream of emigrants from places where pogroms occurred was smaller than from places where the Jews suffered economic hardship but no pogroms.” He is not the first academic to claim this. But what Alroey’s compelling volume makes clear is that Jewish information bureaus played a critical role in encouraging more than 1.5 million Jews to migrate “to all corners of the world” between 1900 and 1914. The presence of these information bureaus, not the Russian Empire’s state-sanctioned terror, correlates with high rates of Jewish emigration.

BREAD TO EAT AND CLOTHES TO WEAR: LETTERS FROM JEWISH MIGRANTS IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY , By Gur Alroey

The end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century witnessed the development of a global industrial information network — the first World Wide Web. Telegraphy, mass-circulation newspapers, railways and rapid postal service changed the speed at which people learned about life beyond their villages. This revolution encouraged many Jews to leave the world of their fathers and seek their fortune elsewhere. Alroey explains that Jewish emigration from Russia reached its zenith in 1906, in a period when pogroms had subsided “because by then potential Jewish emigrants had received more reliable information about employment opportunities abroad from relatives, the local press, and information bureaus.”

Agents of philanthropic, Zionist and territorialist information bureaus fanned out across Russia to circulate agro-industrial reports, dispense advice, distribute funds, cut red tape, arrange for resettlement and track down family members who had disappeared in the melting pot of the New World. Though their ideologies differed, these bureaus all sought to direct Jews to a promised land, be it America or Ottoman Palestine.

The postcard of Friedrich Missler, a travel agent in Bremmen who sent migrants from Germany to the United States, Canada, South America, and South Africa. The writer of the letter is Alter Perling, a homeless wandering Jew, to ITO president Israel Zangwill, 1908. (p. 91) Image by From the Central Zionist Archives.

Alroey’s hybrid book is composed of two parts. In the first, he presents his thesis and the data that support it in a readable though scholarly introduction. The second section consists of translations of historical letters written to various information bureaus in Yiddish and Hebrew. The respective translators, Yankl Salant and Deborah Stern, have captured the elaborate deference, intimate disclosure and sheer panic of the correspondents. Alroey’s volume borrows its title from a plaintive request that comes from a self-described “homeless wanderer,” Alter Perling, who invokes the biblical Jacob’s modest prayer for “bread to eat and clothes to wear.” This missive and dozens of others that Alroey has collected detail the hardships that Jews suffered in Europe, their struggles with the decision to emigrate and the agonies of their displacement in “holding camps” or foreign cities while they awaited passage.

Students of history and the social sciences, as well as amateur genealogists, will appreciate the one-act dramas contained in the letters Alroey has rescued from obscurity. These letters ground historical events in a concrete reality, give faceless statistics individuality and suggest stories behind names on ships’ manifests. Readers of fiction and memoir, however, may benefit the most. The narrative of Jewish immigration to America is already familiar through the works of such authors as Mary Antin, Abraham Cahan and Sholom Aleichem. But this collection of archival correspondence offers a raw sense of immediacy alongside polished canonical works of literature. Readers will recognize the helplessness of Antin’s family as they wait to board their ship in the distress of 34 men detained at a German port; the abandoned wife of Cahan’s “Yekl” in the misery of “wretched, poor” Mashe Zilazne, and the tragi-comic terrors of the arbitrary from Sholom Aleichem’s “Motl” in the simply tragic letter of one Rachel K., who was forced to return to Russia.

The story of immigrants to pre-state Israel is less familiar to Americans. Yet the exchange between a sensitive would-be Yishuv pioneer, 18 year-old Teyvl Kardash, and the Zionist Organization’s Eretz Israel Office evokes the disillusionment felt by the characters in Yosef Haim Brenner’s “Nerves.” Kardash “will not rest” until she leaves her small town to live in Palestine, “the land of [her] dreams.” There she hopes to “work the land” during the day and “study at night.” The tepid response she received from Jaffa — one of the few responses included in the book — must have devastated her: “One cannot hope… for much success at studies after the labors of the day.”

In fact, as Alroey shows, Zionist Organization officials discouraged the majority of supplicants from coming. Contrary to the myths of nation building, Alroey explains that those who helmed the Zionist bureaus believed that America should be the “natural destination of Jewish migrants.” Nearly a century after Kardash confided her dreams in her idiosyncratic Hebrew, one wants to shout down the years: “Go anyway! Go anywhere!” Perhaps she did. Or perhaps she perished far from her dreamland. Her voice, and those of others from these letters that once traversed such great distances, now travel to us through time. We must listen, but whatever our response to them today, it will always be too little, too late.

Adam Rovner is assistant professor of English and Jewish literature at the University of Denver. From 2007 to 2010 he was the translations editor for Zeek: A Jewish Journal of Thought and Culture.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

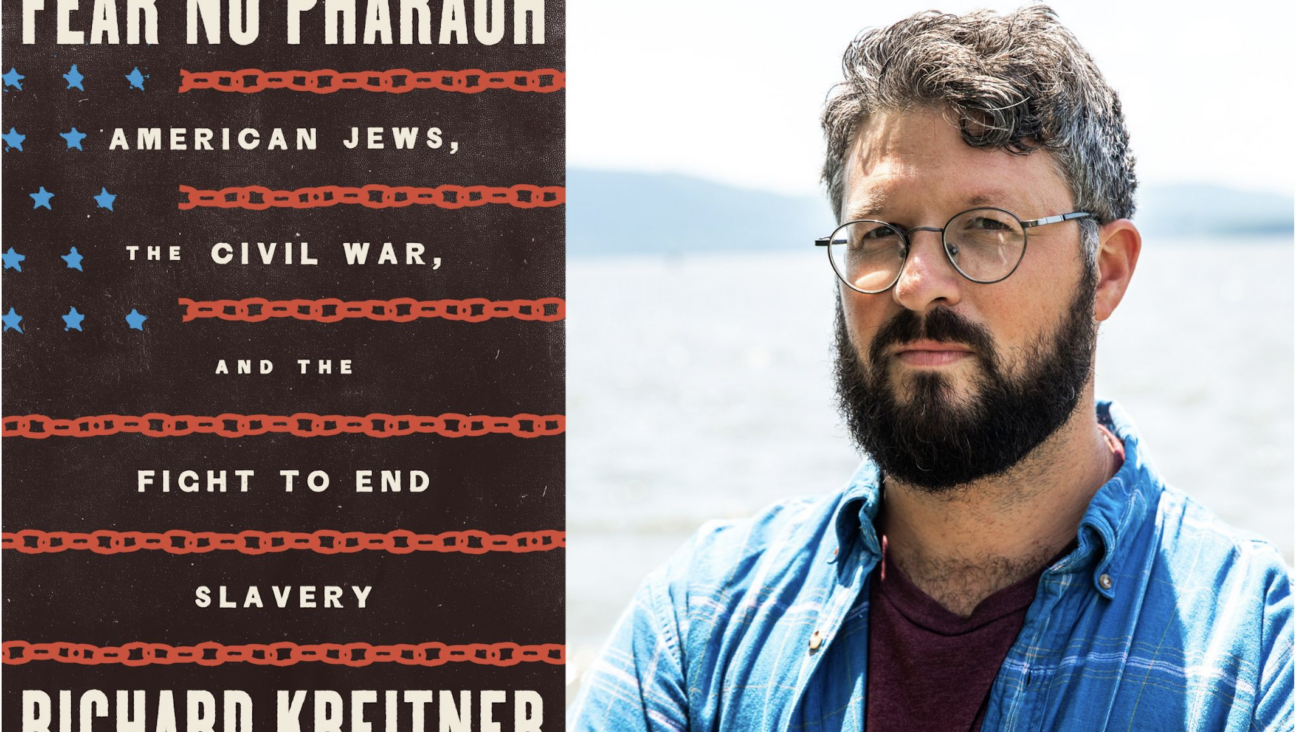

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

- 4

Fast Forward What Mahmoud Khalil says about Gaza and Israel in ‘The Encampments’ documentary

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.