Revisiting the Early Days of the Nazi Comedy

Exactly how popular culture has grappled with Nazism over the past 60-odd years forms a peculiar sort of curve. In films, the trajectory began with stock-villain propaganda and then evolved (in the 1950s and ’60s) toward a defensive, Jewish-comic sardonicism, which found itself capable of using the German fascism as farce. This abated in the ’80s, when it became impossible to joke about so many things, and then the impulse emerged, oddly, after the feel-good trauma of “Schindler’s List,” as comedy again, in the ’90s (“Life Is Beautiful,” etc.). By now, of course, only toll-taking documentaries and occasional sojourns into history, like “The Pianist,” can be tolerated.

Looking back, the Borscht Belt era still puzzles: The caricatures of “Dr. Strangelove,” “The Producers,” “Hogan’s Heroes” and other works managed at that late date to evade the genocide, and they naively mocked Nazis just as Bugs Bunny, Charles Chaplin and Ernst Lubitsch had done during the war. Was it a mass repression? There had to come a moment of confrontation, and it came, slyly, in the form of Robert Shaw’s 1968 play “The Man in the Glass Booth,” which was cheaply and artlessly filmed in 1975 for the American Film Theatre series, and which netted star Maximilian Schell an Oscar nomination. In its abrupt manner, the movie quickly corrected 30 years of evasion in regard to the Shoah, and perhaps singlehandedly made it thereafter impossible to simply jest about the Third Reich and neglect what it did.

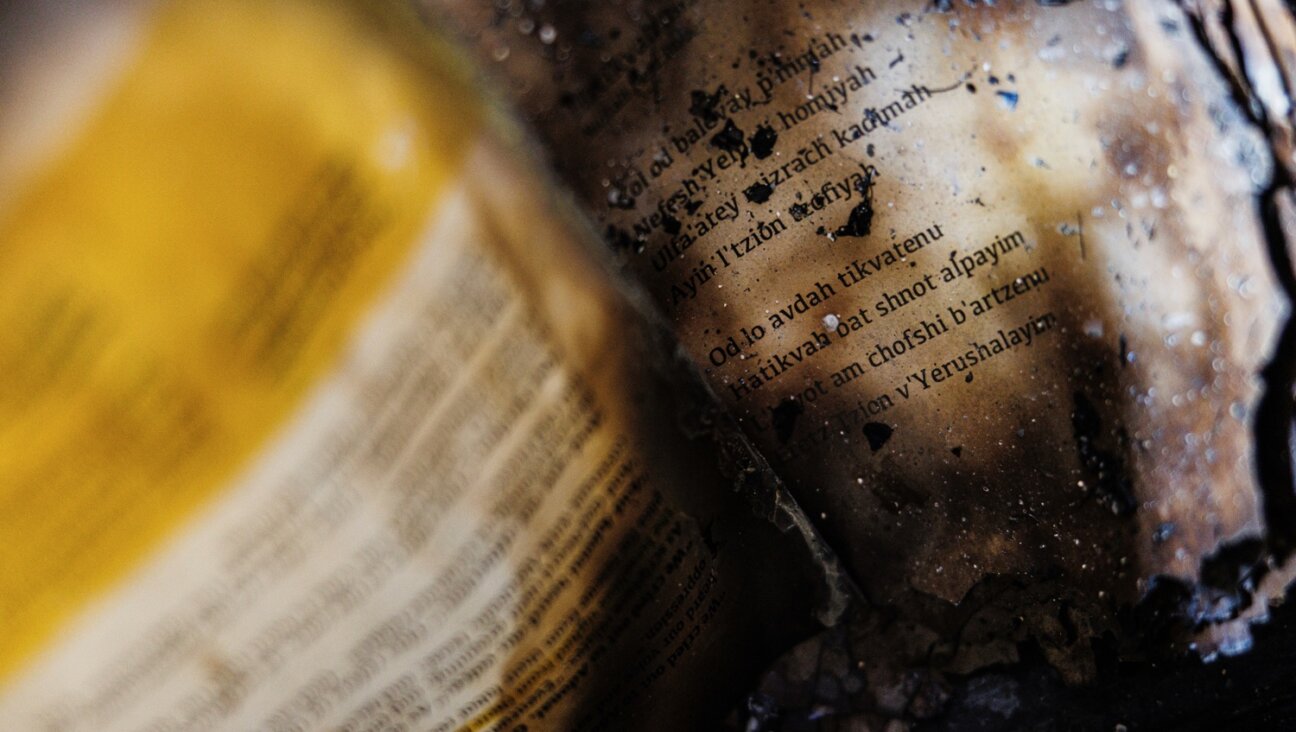

But it’s still an outrageously comic film; motor-mouth irreverence is its modus operandi. Recently released on DVD along with the AFT’s entire 14-movie output, “The Man in the Glass Booth” concerns one Arthur Goldman (Schell), a wealthy, Euro-émigré real estate mogul and widower who by all apparent lights is in the throes of a paranoid, midlife manic breakdown. At least that’s how it seems to us, but he’s so rich that he commands a battery of assistants, doctors and gofers, none of whom dares to question his decisions. Striding through his expansive penthouse on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue in a joyful, jabbering whirlwind of one-liners, explosive pronunciations and argumentative confrontations, Goldman makes it clear that he’s a camp survivor, but one whose idea of remembrance includes quoting Hitler speeches at full throat and making his menschy secretary (Lawrence Pressman) sing “Edelweiss.”

His lust for life is a furious theatrical conceit, keeping the ironic rehashing-history-with-a-grin diatribe raging even as he seems plagued by classic modern-Jewish paranoia (watching for ominous cars through a telescope), and as those delusions turn out to be genuine, with tommygun-toting Nazi-hunters kicking down the door. Is he really a Gestapo criminal hiding in disguise? He zestily insists as much, and his own irreverent brio in regard to Third Reich culture seems to corroborate this. The film’s second half resumes in an Israeli war crimes trial, where the Nuremberg questions of culpability and relative morality are yanked out into the light again from the perspective of the zealous perpetrator — who evades responsibility and makes an energetic case for “socially approved acts!” and for the efficiency of Germany’s efforts at societal engineering and war-winning.

Of course, little is as it seems. Obviously inspired by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Shaw’s play is a creatively engineered piece of rhetoric: The Nazi rationales are both explained and mocked (Goldman is a riotous portrayal of ubermensch hubris), while parallels are delicately drawn to more contemporary situations (“You people don’t want peace!” Goldman hollers at his prosecutors. “You people want war!” He doubles the bet by alluding to Vietnam — “My Lai was a classic!” he crows, a line that could not have been in the play and was probably added by screen adapter Edward Anhalt.)

Shaw, a prolific novelist and famous as an actor for roles in “From Russia With Love,” “A Man for All Seasons” and “Jaws,” reportedly didn’t like the adjustments made to his text (his name doesn’t appear in the credits), but he had to appreciate Schell, whose performance is one big exclamation point, fuming and hallucinating from behind fish-eye glasses and using up 90% of every room’s oxygen. It was an inspired casting coup, thanks to the echo chamber it creates with Schell’s Oscar-winning turn as the defense attorney in 1961’s “Judgment at Nuremberg”; the same conundrums are put on trial in both films, only this time Schell tries to unravel them from the inside out. The difference is, of course, that “The Man in the Glass Booth” eschewed the brooding respectfulness of Holocaust discourse and dared for Galgenhumor instead, the better to contextualize what was indisputably human and yet will always seem unimaginable.

Michael Atkinson served for a number of years as a film and book reviewer for The Village Voice.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Chicago man charged with hate crime for attack of two Jewish DePaul students

-

Fast Forward In the ashes of the governor’s mansion, clues to a mystery about Josh Shapiro’s Passover Seder

-

Fast Forward Itamar Ben-Gvir is coming to America, with stops at Yale and in New York City already set

-

Fast Forward Texas Jews split as lawmakers sign off on $1B private school voucher program

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.