Fight Over Jerusalem in the Pages of a Passport

Why is it, friends of Israel often ask, that the Jewish state is the only country in the world that’s not allowed to name its own capital city? King David chose Jerusalem as capital of the original Jewish state 3,000 years ago. And yet America refuses to place its embassy there, despite repeated acts by Congress requiring it. Neither does any other country in the world. The United States won’t even allow American citizens born in Jerusalem to have their passports show Israel as their birthplace. Their passports simply say “Jerusalem.”

After years of skirmishing, these questions will come before the U.S. Supreme Court this November. The specific case is a narrow one: An American couple, Naomi and Ari Zivotofsky, sued the State Department in 2004 to put “Jerusalem, Israel” in the passport of their son Menachem, born in 2002 in Shaare Zedek Hospital in west Jerusalem.

When the high court accepted the case last May, however, it directed the sides to address a broader question: May Congress and the courts dictate foreign policy to the Executive Branch? If the Zivotofskys win, therefore, it could begin to unravel a decades-old U.S. policy that defines the entire city of Jerusalem as “disputed territory” rather than sovereign Israeli soil.

The legal issues here are excruciatingly complicated. The Zivotofskys cited a 2002 law signed by President George W. Bush that requires the State Department to put “Jerusalem, Israel” as a birthplace on an American’s passport when so requested. The administration fired back by citing a statement by the same President Bush after signing the law that he would not enforce it. The law, Bush wrote, would “impermissibly interfere with the President’s constitutional authority” to “speak for the Nation in international affairs, and determine the terms on which recognition is given to foreign states.”

Now it gets confusing. The Zivotofskys’ attorney, the conservative-leaning constitutional lawyer Nathan Lewin, argued to the court that Bush’s use of “signing statements” to disavow laws after signing them was unconstitutional. A pack of conservative commentators then piled onto the Obama administration, calling it hypocritical for relying on the Bush signing statement, given candidate Barack Obama’s own denunciations of such statements as unconstitutional. None of the conservatives skewering Obama for quoting Bush bothered questioning Bush’s own inconsistency.

An impressive list of supporters has filed friend-of-the-court briefs for the Zivotofskys. The Anti-Defamation League filed one brief for itself and 10 other organizations, including major Orthodox, Conservative and Reform groups. The Zionist Organization of America filed its own brief. Another was filed by a group of 28 senators, led by Republican Jon Kyl, Democrat Carl Levin and Independent Joseph Lieberman. Yet another was filed without cosigners by then-representative Anthony Weiner of New York, who has since resigned because of his, um, other briefs.

Notably missing is the American Jewish Committee, which told the JTA that it views Jerusalem as Israel’s capital but opposes unilateral moves that preempt negotiations.

The State Department’s Jerusalem policy grows out of the 1947 U.N. resolution partitioning then-Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. The plan made Jerusalem an international entity under U.N. rule. Israel, however, held the city’s western half when the 1949 armistice agreements were signed, ending its independence war against invading Arab states. The United States, like most other countries, recognized the armistice lines as informal borders, but still viewed Jerusalem as international territory. The Truman administration, noting the city’s sensitivity, insisted its fate be left to peace negotiations. Every president since has reaffirmed this.

Congress first challenged the policy in a 1995 law requiring that the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv be moved to Jerusalem by 1999. The bill was introduced in the Senate by Republican presidential hopeful Bob Dole. Then-president Bill Clinton saw it as a challenge to presidential authority, but hesitated to veto it with an election looming. Instead he took no action, a technicality making it law after 10 days.

The law also infuriated Israel’s then-prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, who privately complained that it disrupted his negotiations with the Palestinians but that he couldn’t openly oppose it because of his own voters. At his and Clinton’s insistence, the bill allowed the president to waive the rule every six months on national security grounds.

The constitutional debate centers on a clause in Article II that the president “shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers.” Courts have ruled since 1839 that this means the president is solely responsible for recognizing foreign sovereignties. The administration claims the passport, as an official government document, reflects policy. The Zivotofskys’ brief counters that it’s merely a form of identification. It says the case is just a matter of “individual liberties”—specifically a citizen’s “right to be identified in official governmental documentation by the country he recognizes as his birthplace.”

Speaking to reporters, attorney Lewin was even more dismissive, saying young Zivotofsky speaks for many Jerusalem-born Americans who are “proud of the fact that they were born in Israel” and “want their passports to reflect that fact.” You might think he was selling Yankees T-shirts.

In fact, Lewin said, the dispute is “really a tempest in a teapot created by the State Department,” as though the government had filed the federal lawsuit, not the Zivotofskys.

The case is nothing of the sort, of course. That’s why it’s so heated. The passport is probably the most closely-guarded document the government issues to citizens. Rewriting it, the administration claims, “would critically compromise the United States’ ability to help further the Middle East peace process,” considering that the “status of Jerusalem is one of the most sensi-tive and long-standing disputes in the Arab-Israeli con-flict.”

Which brings us back to our original question: Why is Israel the only country in the world that’s denied the right to name its own capital? Answer: because it’s the only country that proclaims its capital on territory that no other country in the world recognizes as its sovereign soil. Someday a treaty will be signed affirming Israeli sovereignty there, may it come speedily. But that hasn’t happened yet.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Make a Passover Gift Today!

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion What Jewish university presidents say: Trump is exploiting campus antisemitism, not fighting it

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Ben Shapiro, Emily Damari among torch lighters for Israel’s Independence Day ceremony

-

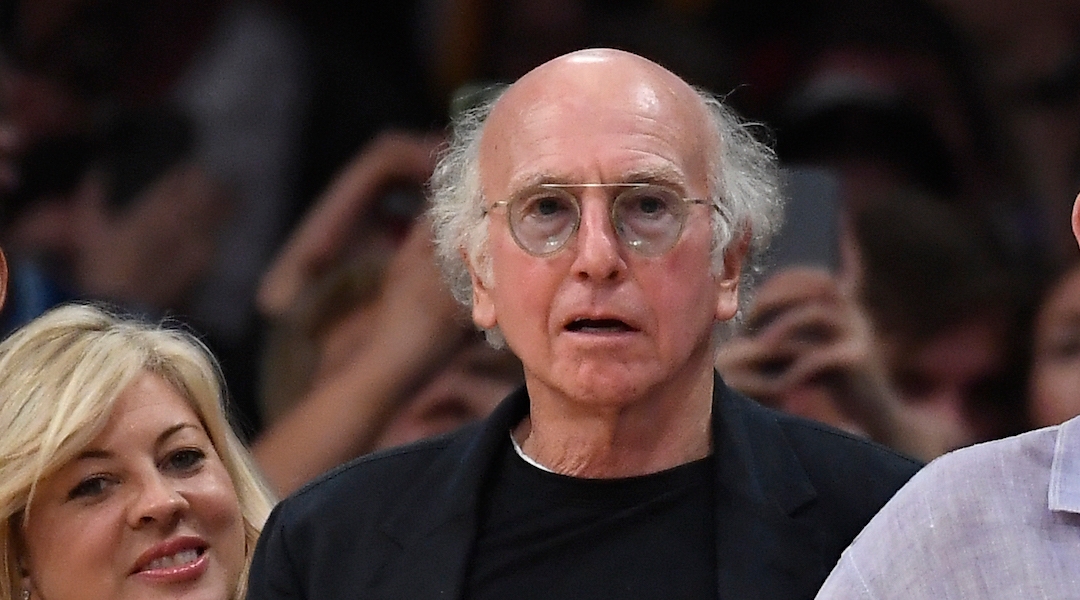

Fast Forward Larry David’s ‘My Dinner with Adolf’ essay skewers Bill Maher’s meeting with Trump

-

Sports Israeli mom ‘made it easy’ for new NHL player to make history

-

Communications The Forward Announces Gifts of Domains Yiddish.com and Yiddish.org by Elie Hirschfeld and his wife Sarah Hirschfeld, MD

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.