A Palestinian State Even the Securocrats Accept

I don’t think I’d be going out on a limb to suggest that Israel is having a bit of a rough patch lately, what with its Cairo embassy in ruins, terrorism flaring in the south and new troubles brewing at the United Nations. I could drone on about the dangers, but I don’t need to. I happen to have a handy list, itemized the other day at the Harvard Club by former National Security Council anti-terrorism chief Richard Clarke.

In Clarke’s view, Israel faces seven main threats right now: the rupture with Islamist-led Turkey; chaos in Egypt; the “Hezbollah government” in Lebanon; extreme instability in Libya; the looming declaration of Palestinian statehood at the United Nations; the “ascent” of soon-to-be-nuclear Iran, and “the diminution of American power and influence.”

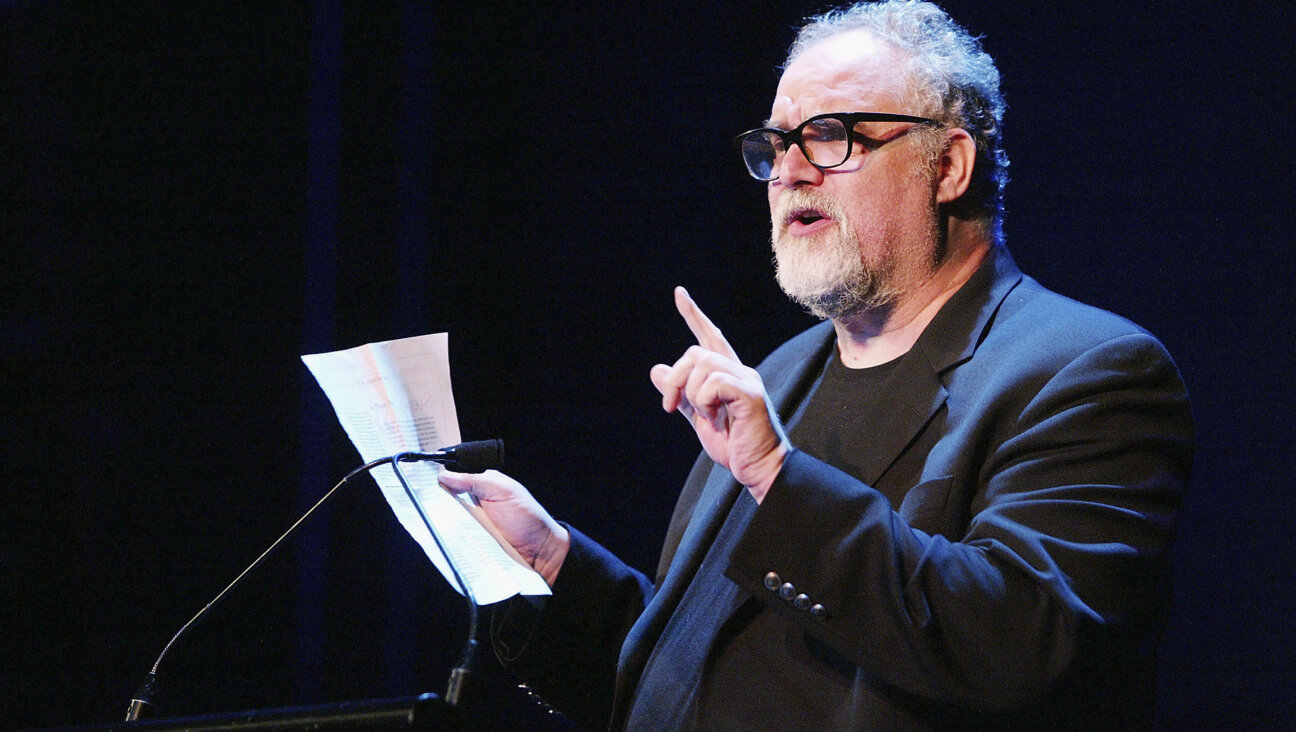

Clarke was addressing a day-long symposium on Israeli security sponsored by the liberal-leaning Israel Policy Forum. By the time he was done, everyone in the room — a collection of dark-suited business types, American and Israeli military and intelligence officials and assorted wonks — seemed ready to run home and crawl under their beds for a year.

The gloom was promptly lifted, however, by a positively chipper presentation from the next and final speaker: Efraim Halevy, former director of Israel’s Mossad intelligence service, a man not usually known for spreading sunshine.

Halevy’s basic message: If the strategic map of the Middle East looks like a lemon, make lemonade. Or, as he put it: “In a situation where the most probable outcome is the least desirable and the most desirable is the least probable, you go halfway. Sometimes a half a cup of coffee is better than a full cup of coffee” — that is, when a full cup isn’t available.

There are several layers of meaning to this little maxim. At the most overt level, he was talking about the possibility of Israeli-Palestinian peace. For Israel today, he said, “the best possible solution is a complete peace between Israel and Palestine. But I think it’s the least probable.” The most probable solution, he said, is “no solution — more of the same,” muddling along toward “either a one-state solution, with all that entails, or chaos.” That’s the “least desirable,” but “the most probable.”

So what’s he offering in his half-cup of coffee? He didn’t spell it out at the Harvard Club, but he’s done so in Israel several times recently. He believes Israel should offer to recognize a Palestinian state within provisional borders, and then enter state-to-state negotiations over the issues in dispute: borders, water rights, demilitarization, refugees, Jerusalem.

If you follow these things, you know that this view is shared by another Israeli defense heavyweight: Shaul Mofaz, former chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, former defense minister, currently chair of the Knesset foreign affairs and defense committee and number two in the Kadima party. Mofaz proposed the provisional borders idea in his own “peace plan” in 2009, shortly after the last elections.

One hitch is that the Palestinians have publicly rejected provisional borders, suspecting that they would become permanent. Mofaz’s plan would sidestep that fear by obtaining international guarantees that a final border will be based on — though not identical to — the pre-1967 ceasefire lines. Halevy has endorsed the based-on-1967 formula privately, but he’s only hinted at it in public.

There’s a version of this idea under consideration right now among the Palestinian leadership. European diplomats told Haaretz that representatives of the European Union are negotiating with the Palestinians to soften their U.N. statehood proposal so it doesn’t call for specific borders. Instead, it would ask Israel to negotiate with a newly declared Palestinian state over borders and other issues. Whether the Palestinians buy it may depend on whether Jerusalem, or at least Washington, can be convinced. That’s a long shot. The Netanyahu government views the entire Palestinian U.N. gambit as an attack on Israel’s legitimacy. It’s almost unimaginable that Washington would break ranks.

Now, finding a couple of ex-generals on the opposing side of the barricade from their own government isn’t terribly strange. Israel has always had a few oddballs.

But Mofaz and Halevy aren’t oddballs. They are among the most conservative of Israel’s former defense chiefs. Both were appointed to their senior commands by Netanyahu himself, during his first stint as prime minister in the 1990s. Their advocacy of provisional Palestinian borders puts them firmly on the right wing of Israel’s defense establishment. Of the 19 living ex-chiefs of Israel’s three main security services — IDF, Mossad and Shin Bet — only one is further right.

That would be former IDF chief of staff Moshe Yaalon, currently a minister in the Netanyahu cabinet, who believes today’s Palestinian leadership is not interested in peace and a Palestinian state would put Israel in danger. Almost all the others openly favor negotiating a two-state deal immediately, with the 1967 lines as a baseline.

Here is a rough roll call: Of the six living ex-IDF chiefs, all but Yaalon favor a Palestinian state with borders based, either now or eventually, on the 1967 lines. Of six living ex-Shin Bet chiefs, all say likewise except Yuval Diskin, who retired this summer and hasn’t yet spoken publicly. Of seven living ex-Mossad chiefs, the three oldest haven’t spoken out lately; all the others publicly support the positions described.

Think about it. These are the people who have overseen Israel’s defense for more than a generation. The military chiefs believe, almost unanimously, that Israel could be secure living alongside a Palestinian state with adjusted 1967 borders. The intelligence chiefs believe almost unanimously that the Palestinians would settle for what Israel can safely give. They all believe Israel would be safer that way. Put differently, that the current alternative makes Israel less safe.

Does their military background entitle them to dictate policy? No one suggests that. Most say they’d rather not be speaking out at all, given the rules of democracy. But they think things are going badly, and it needn’t be that way, and they think the public is entitled to know.

If one or two of them argued against the government’s policies like this, you’d call them eccentric. If a rump group rebelled, you might call it a surprising debate. But this is almost unanimous. That raises a different question: Why are the politicians endangering their people?

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

- 2

Opinion Trump’s Israel tariffs are a BDS dream come true — can Netanyahu make him rethink them?

- 3

Fast Forward Cory Booker’s rabbi has notes on Booker’s 25-hour speech

- 4

News Rabbis revolt over LGBTQ+ club, exposing fight over queer acceptance at Yeshiva University

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Can Israel’s love for Trump survive his coming negotiations with Iran?

-

Opinion Is this extremist Zionist group trying to protect Israel — or just punish left-wing Jews?

-

Fast Forward Conservative movement softens support for two-state solution

-

Theater William Finn, Tony-winning writer of queer, Jewish musicals dies at 73

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.